One of the never ending discussions I’ve been involved since I have shifted career from evolutionary biology to philosophy of science is the issue of scientism. Heck, I have even co-edited (with my friend Maarten Boudry) a book about the darn thing. So let’s put the matter to rest once and for all!

Just kidding. I’m under no illusion that this essay will be the last word on the topic. Still, I have to try. The impetus for what you are now reading came from a recent article by Moti Mizrahiis, associate professor of philosophy in the School of Arts and Communication at the Florida Institute of Technology, entitled Why not scientism? and published in Aeon magazine. It opens thus:

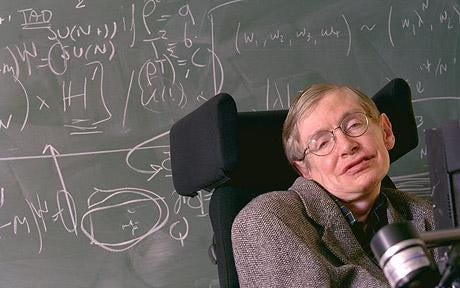

“‘Philosophy is dead,’ Stephen Hawking once declared, because it ‘has not kept up with modern developments in science, particularly physics.’ It is scientists, not philosophers, who are now ‘the bearers of the torch of discovery in our quest for knowledge.’ The response from some philosophers was to accuse Hawking of ‘scientism.’ … But what’s wrong with putting a higher value on science compared with other academic disciplines? What is so bad about scientism? If physics is in fact a better torch in the quest for knowledge than philosophy, as Hawking claimed, then perhaps it should be valued over philosophy and other non-scientific fields of enquiry.”

Let me explain what’s wrong with it. To begin with, Hawking wrote that piece of nonsense right at the beginning of The Grand Design, a book co-written with Leonard Mlodinow which is best characterized as one long discussion centered on philosophy of science. How ironic.

Second, it is simply factually false that “philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science,” and only someone profoundly ignorant of philosophy, as Hawking surely was, could write such a sentence. There is an entire field of philosophy devoted to science, with a number of specialized fields in the philosophy of biology, of quantum mechanics, of cosmology, and so forth. The people who work in such fields very much keep up with the corresponding sciences, otherwise they would have nothing to say about them.

Third, it is a gross category mistake (a philosophical concept that physicists really ought to study) to complain that philosophy is useless because it hasn’t solved any scientific problems, of late. It’s like saying that musical theory is useless because it hasn’t produced any symphony. It is simply not the business of musical theory to do any such thing, so complaining about the alleged failure is silly and ought to be embarrassing.

More specifically, there are three disciplines that study science from the outside: philosophy of science, history of science, and sociology of science. The first one is concerned with the logic of scientific discovery and the epistemic warrants deployed by scientists for their theories; the second one tries to understand the development of different sciences through time; and the third one treats science as a human activity, characterized by power structures, financial interests, individual passions, and so forth. None of the three counts as its objectives to answer scientific questions, because, you know, we have science for that!

Fourth, pace Mizrahiis, his use of the word “knowledge” is ambiguous and unhelpful. More on this in a moment.

He proceeds by defining scientism in one of two ways: (i) The thesis that scientific knowledge is the only form of knowledge we have; (ii) The thesis that scientific knowledge is the best form of knowledge we have. The first one is demonstrably false, the second one nonsensical.

Scientific knowledge is most certainly not the only form of knowledge we have. Mathematicians produce knowledge, and mathematics is not a science, because its results are independent of any empirical finding concerning the outside world. The Pythagorean theorem, for instance, is true regardless of any actual triangle out there. Or take logic, which is very similar to math. Logical theorems can be shown to be true, but logic is not usually considered a science, for the same reason I just adduced concerning mathematics.

Moreover, we can have knowledge of, say, English literature during the Elizabethan period, or of artistic movements during the early 20th century. We can have knowledge of how to ride a bicycle, or how to navigate the New York subway system. I can have knowledge of the habits of my wife because I live with her, and I know how to write an essay on Substack. The examples are endless. No, scientific knowledge most certainly is not the only kind of knowledge out there.

Still, is it the best kind of knowledge? Well, that’s a value judgment, and values are inherently human concepts, they are not out there in the world, and they cannot be objectively ranked. The best knowledge according to whom? Based on what criteria? Without articulating more precisely what we mean by knowledge and how we measure “best” the statement makes no sense. I’ll return to this below.

Mizrahiis also introduces a distinction between methodological and metaphysical scientism: methodologically, scientism is the notion that scientific methods are either the only or the best ways of knowing about reality. Metaphysically, scientism is our only or best guide to what exists.

The first definition concerns epistemology (what we know and how), the second one ontology (what exists). Contra to what implied by Mizrahiis, the two are not at all independent, as ontological claims need an epistemological foundation to back them up. Either way, the author is still using “knowledge” as a monosemic word while it is polysemic, as shown above. This ambiguity generates enough confusion in the reader to make his arguments seem plausible while they aren’t.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Philosophy Garden: Stoicism and Beyond to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.