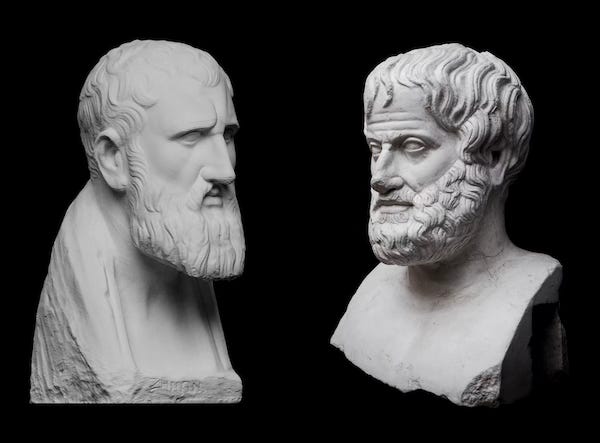

Aristotle vs the Stoics: part I, metaphysics and logic

Were the Stoics just copying Aristotle? Spoiler alert: not really.

[Cato] “I admit that some parts [of Stoic teachings] are obscure, yet the Stoics do not affect an obscure style on purpose; the obscurity is inherent in the doctrines themselves.”

[Cicero] “How is it, then, that when the same doctrines are expounded by the Peripatetics, every word is intelligible?”

[Cato] “The same doctrines? Have I not said enough to show that the disagreement between the Stoics and Peripatetics is not a matter of words, but concerns the entire substance of their whole system?”

[Cicero] “O well, Cato, if you can prove that, you are welcome to claim me as a whole-hearted convert.”

The above exchange comes from the beginning of the fourth book of Cicero’s On the Ends of Good and Evil, one of my favorite books from antiquity, with a stupendous title to boot. In book three Cicero had given Cato the Younger, the archenemy of Julius Caesar and a famous Stoic role model, the floor to expound Stoic ideas. In book four Cicero puts on his skeptical cap and challenges Cato on a number of points.

From the get go the major challenge is not that the Stoics are wrong, but that they differ only in (more or less obscure) wording from the Peripatetics, the followers of Aristotle. Cicero had an agenda in suggesting a high degree of similarity between Stoicism and Peripateticism: his allegiance was to the Skeptical Academy, and he was influenced by Antiochus of Ascalon, the Academy’s Scholarch who attempted to forge a syncretic philosophy that merged Platonism, Aristotelianism, and Stoicism, thus beginning what is known as Middle Platonism.

Nevertheless, the question is a good one, and it has been raised time and again over the centuries: is Stoicism a new philosophy, compared to Peripateticism, or is it just the latter dressed up in fancy and perhaps even misleading language?

In order to explore the topic with people who know what they are talking about, I recently organized a practical philosophy seminar in Athens together with my colleagues John Sellars and Rob Colter (both of whom are faculty at the School for a New Stoicism). John has written several pertinent books, including Lessons in Stoicism, and more recently Aristotle: Understanding the World's Greatest Philosopher. Rob is the founder of the original Stoic Camp in Wyoming, and a professor of ancient philosophy at the University there. The goal of the seminar was to introduce students to the two philosophies and to compare them to see whether Cato or Cicero had a point. (By the way, many thanks to Anna Kanta for her incredible help with the logistics!)

By the end of our discussions, we came up with a systematic comparison between Stoicism and Aristotelianism, organized according to the three classical fields of study in ancient philosophy: metaphysics, logic, and ethics. Let’s take a look.

There is indeed much overlap between the two philosophies, which is not surprising because they are both influenced, through different paths, by Socrates. Aristotle inherited and reacted to Platonism, while the Stoics took on board a number of ideas from the Cynics and the Megarians, among others. So, for instance, both Aristotelianism and Stoicism are types of eudaimonism, meaning that they argue that “happiness,” broadly construed, is what every human being ultimately wants. They are also both types of virtue ethics, that is, philosophies that consider virtue to be necessary for a meaningful human life. Here, though, I’m going to focus on the differences, and eventually show that Cato had a better argument than Cicero. (Of course, don’t forget that “Cato” above was Cicero using a historical figure to express certain ideas that he went on to criticize, in perfect skeptical fashion.)

Metaphysics: God and the nature of the cosmos

Aristotle thought that the universe is eternal, without a beginning or end. By contrast, the Stoics believed that it is highly dynamic, going through repeated, infinite cycles of birth and destruction. Stoic metaphysics, in this respect, clearly derived from the Presocratic philosopher Heraclitus of Ephesus, the originator of what nowadays is called process (as opposed to object) philosophy: everything is a pattern in fluctuation, there are no fixed things in the world, despite appearances to the contrary. (This doctrine appears to be in line with the latest from fundamental physics.)

The two approaches also differed dramatically in their conception of God. For Aristotle, this was the “Prime Mover,” the first cause that gets everything else going. It is, in itself, unmoved, because it has no cause. The Stoics where pantheists, they believed that the universe is God, that it is alive, and that it is characterized by the Logos, the highest form of the pneuma (breadth) that infuses matter throughout the cosmos, and which makes rational thought possible.

While both conceptions acknowledge the inherent rationality of the universe, Aristotle is typically interpreted as not leaving much room for the notion of divine providence, something that created a bit of a headache for his otherwise favorable Christian commentators throughout the last couple of millennia. The Stoics, by contrast, have a robust idea of providence, though it is one in which things happen to us not as the result of a plan devised by a benevolent god, but rather in the service of the wellbeing of the cosmic organism. As Epictetus says (e.g., Discourses 2.5), we are like an organ, say a foot, attached to the cosmic body. Our purpose in life is to do whatever is good for the body, no matter how unpleasant it may be for us. If the body has to cross a muddy path in order to get home, then we, as the foot, ought to be happy to get dirty and wet.

Stoicism and Peripateticism also differ significantly in their conception of the soul: it is divided into three components for Aristotle, while it is unified for the Stoics. In De Anima, Aristotle distinguishes between vegetative, sensitive, and rational soul. The vegetative soul is in charge, so to speak, of growth and reproduction, and is possessed by plants, animals, and humans. The sensitive soul has to do with mobility and sensation, and is found only in animals and humans. The rational soul allows thoughts and reflection, and is characteristic only of the human species. This is clearly a modification of Plato’s theory, as expressed in the Republic and in Phaedrus, though for Plato the soul was immaterial and immortal, while for Aristotle it is made of stuff and cannot exist outside of the body.

The Stoics also thought that the soul is made of matter, because everything that has causal powers must be. However, they thought that there is only one unified soul, and that its various characteristics—which also distinguish plants, animals, and humans—are all the result of different “tensions” of the same underlying principle, the above mentioned pneuma. I will discuss one important consequence of the difference between the two philosophies in this respect next time, when we will compare Aristotelian and Stoic moral psychology.

Logic: term vs propositional

Aristotle and the Stoics together comprise much of what the Greco-Romans did in the area of logic. And their impact is felt still today. Not only Aristotelian and Stoic syllogistics were studied throughout the Middle Ages, but the first one still provides the basics for contemporary students of logic and the second one was only improved upon at the beginning of the 20th century. (Indeed, Gottlob Frege, the alleged father of modern logic, probably plagiarized the Stoic Chrysippus!)

The main difference between the two approaches is that Aristotle articulated what we today call “term” logic, because it uses as its basic elements individual terms, such as “Socrates,” or “men.” Contrast this with the Stoic so-called propositional logic, which governs entire propositions. Propositional logic is considered the foundation of all higher-level logics that comprise the modern field.

Here is an example of Aristotle-style term logic, italics indicating the key terms:

All men are mortals

Socrates is a man

(Therefore) Socrates is mortal

This famous syllogism, by the way, is nowhere to be found in Aristotle’s writings, though a version of it is articulated by Sextus Empiricus’s Outlines of Pyrrhonism.

The formal structure of the syllogism is:

All A’s are B’s

C is an A

Therefore C is a B

And here is an example of Stoic-style propositional logic:

If it’s raining then it’s cloudy

It’s raining

(Therefore) It’s cloudy

Whereby each line represents a proposition. The formal structure looks like this:

If P then Q

P

Therefore Q

The two approaches are usually seen as complementary, not antagonistic, with the Stoic one being of broader application than its Aristotelian counterpart.

[Next time: the ethics!]

Quantum Physics is more subtle than the distinction between everything fluctuating and everything static.

While the ground state of a system (like a 'quantum vacuum' or a harmonic oscillator) is often described in pop lit as fluctuating, the state they are in does not change with time. It has all its positions and motions at the same time, i.e., they are superimposed. If you ask what's the probability of finding a particle at a position that does not change with time, but in a wave/excitation-like manner, it is at all possible positions at the same time. The 'amount' (probability amplitude' at any given position does not change.

Calling this state of affairs 'ground state fluctuations' seems highly misleading to me though it is admittedly a difficult concept to get across.

One might regard quantum superposition as the ultimate synthesis of Heraclitus and Paramindies.

Massimo, I heard a philosopher here in Brazil suggest that materialism has limits in explaining non-material phenomena, such as why the sum of all the internal angles of a triangle is 180º. How can we explain this? Is it because our mind, being attached to the material body, must use it to identify mathematical axioms?