Birthday meditation on death

Once in a while it’s good to reflect on your own mortality. What better time than your birthday?

week it was my birthday. N. 59, to be precise. I’ll soon have to think of something special to celebrate the big 6-0, as obviously arbitrary as that number actually is. (We ten-fingered primates are obsessed with base ten counting, though I must admit the decimal system is awfully convenient.)

This year, though, I decided to take a stroll with my wife in the beautiful Greco-Roman galleries of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, where we live. It’s not that we hadn’t had enough exposure to that sort of thing of late, as we had just come back from a ten-day trip to Rome. It’s that Greco-Roman statuaries (and buildings) are some of the things that trigger a feeling of awe in me (together with certain pieces of music, some examples of architecture, some novels, and pretty much every astronomy photo ever).

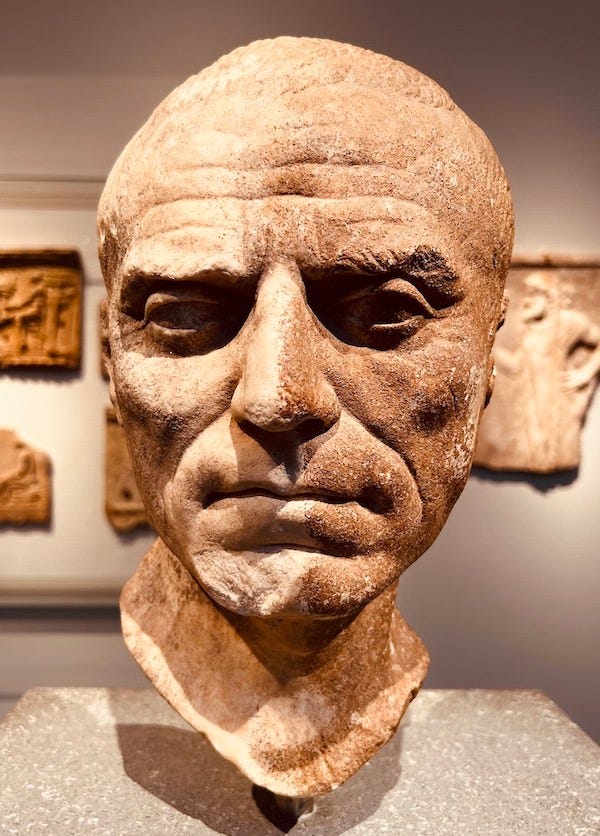

On that day, however, I wasn’t looking for the obvious. The bust of Marcus Aurelius, say. Or those of Socrates and Epicurus. Or Homer. Nor was I attracted by the incredible frescos that once decorated a Roman villa, or by the Etruscan chariot on display on the mezzanine. What I wanted instead was to contemplate the faces of ordinary Greco-Roman men, women, boys, and girls, like this one, for instance:

These ordinary people are gone just as much as Marcus, Socrates, and all the rest. But unlike their more famous counterparts, they have disappeared from human memory a little bit earlier. No doubt they’ll eventually be joined in their oblivion by the ones we still remember. Very soon, in the cosmic scale of things. And since I don’t fancy myself a Socrates, I feel more kinship with the anonymous group. Which is why I wanted to spend some time with them.

You may think that this is all a bit too gloomy and even morbid, especially on the occasion of a birthday. But from a Stoic perspective death is simply one more natural process, a necessary and inevitable stage of life. Moreover, there is nothing terrible in not being remembered. After all, you won’t be there to care anyway!

Entirely by coincidence, this is also the period during which I’m reading How to Die, a collection of modern translations of essays by Seneca on the topic of mortality, part of Princeton University Press’s “Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers” series. You see, I’ve issued myself, and Princeton’s editor Rob Tempio, a challenge that I will go through the entire collection (which stands at 24 books right now, and I’m told there are four more entries in the works). You can read my commentaries so far here, here, here, and here. How to Die reminded me that nobody does death quite so charmingly and profoundly as Seneca:

“Whatever existed before us was death. What does it matter whether you cease to be, or never begin? The outcome of either is just this, that you don’t exist.” (Epistle 54)

He is using a standard Epicurean tactic to assuage our natural fear of death, the so-called symmetry argument. The idea is that we are so worried about not existing for an eternity after we die, and yet we are not bothered at all by the fact that we have also not existed for an eternity before we were born. The only difference between the two intervals of time is how we think about them. And a basic Stoic concept—central to the philosophy of Epictetus—is that we should always keep firmly in mind the difference between facts, which are mind-independent features of the world, and opinions, which are entirely ours, and can, therefore, be challenged and changed, though that requires effort.

Consider the four heads in the photo above. The one on the left is of an unknown Roman woman of the first century of the modern era. The one next to it is from an equally unknown Greek goddess, dating three centuries earlier. Then there is a (again, unknown) Greek queen from the first century BCE, and finally another unknown Greek goddess, the older of the group, dating from the 3rd or 2nd century BCE.

They all could be people you know, accounting for differences in hairstyle. Indeed, had you lived in any of those places and times, you might have seen the models who posed for these sculptures walking around town. You might have known their names, and perhaps even some gossip about themselves, their relationships, their families and friends. Now the only testimony of their very existence are four anonymous heads, in different states of preservation, on display in a museum located 8,000 kilometers from where they lived and two millennia into their future. Does that not inspire awe in you?

Why, exactly, are we so worried by death? Surely part of the answer is that we have been told horrible stories about what might happened to us once “there,” even though there is no there to go. Such stories are often how authorities—religious and political ones—manipulate us into submission to their agendas. Seneca saw this very clearly when he wrote:

“Consider that the dead are afflicted by no ills, and that those things that render the underworld a source of terror are mere fables. No shadows loom over the dead, nor prisons, nor rivers blazing with fire, nor the waters of oblivion; there are no trials, no defendants, no tyrants reigning a second time in that place of unchained freedom. The poets have devised these things for sport, and have troubled our minds with empty terrors.” (To Marcia, 19.4)

There is no afterlife, for the simple reason that death is—by definition—the cessation of all awareness and feelings. It follows that there is no reason for us to be terrorized by the stories told by poets (and, especially, priests). There is nothing that death is like, so there is no point in wandering about it.

Of course, the process of dying is another story. For some lucky few it is sudden and painless, but for others it is protracted and painful. Even so, the Stoics remind us, such pain can either be endured, because it isn’t too acute; or, if it is acute, it won’t last long because it will kill us. Failing either, we always have the option of walking out ourselves, suicide being the ultimate source of freedom, the way out of the smoky room, as Epictetus colorfully puts it.

As Seneca says, we die every day, from the very moment we are born. Our time is limited, even though we don’t know what that limit is. But does it matter? May be not:

“In what way were eighty years, passed in sloth, a benefit to someone? He didn’t live but only lingered in life; he didn’t die late, but died for a long time. ‘He lived eighty years.’ Yes, but it matters up to what point of death you are counting. ‘He died in his prime.’ Yes, but he had carried out the duties of a good citizen, a good friend, and a good son; he lacked nothing in any of these paths. His lifetime was cut short, but his life was completed. ‘He lived for eighty years.’ No, he merely was for eighty years, unless you say ‘he lived’ in the same way we say that trees live.” (Epistle 93)

I simply love this passage. “He lived for eighty years. No, he merely was for eighty years.” Unfortunately, I know exactly what Seneca means here. I am acquainted with people who have been around for decades, in some cases a good number of them, and yet the best it can be said of such people is that they were, not that they lived. Some of them are dimly aware of it, and tell me that they can’t wait to be gone. Others are entirely oblivious to the point, and will likely fight death tooth and nails. Many American families go into bankruptcy because of aggressive end-of-life “care” they wish, or are pushed to provide, for their loved ones.

Once we accept that human life is not only limited, but exceedingly short in the cosmic scheme of things, it acquires meaning. Every moment counts, which is why we need to pay attention, prosoche in Epictetus’s word, to everything we do, as well as to why we do it. What matters to you? Are you doing it now, or are you postponing it in order to do something else that you’ll regret wasting time on once you’ll be on your death bed? Nothing has ever been improved by not paying attention to it, and your life—the only one you have—is certainly worth paying attention to. Right here, right now.

“Just as with storytelling, so with life: it’s important how well it is done, not how long. It doesn’t matter at what point you call a halt. Stop wherever you like; only put a good closer on it.” (Epistle 77.5-20)

I’m considering the possibilities for my own “closer,” but in the meantime I’m working on what is important to me now. That’s why I’m writing this, because writing is an integral part of my life. That’s why I took that stroll in the Metropolitan with my wife, who is such an important part of that life. That’s why I was thinking of my daughter, currently living in Washington, DC, and why I wished she could have been there with us. But we are planning to go see her soon, because it’s important, and because we don’t know how much more time we have.

After our quiet meditations among Greco-Roman statuaries my wife and I took an evening stroll in Central Park and reached our destination. We had dinner at one of my favorite restaurants in New York, Robert’s, on top of the Museum of Art and Design, with a gorgeous view of Columbus Circle. Because life needs to be lived hic et nunc.

Hi, thanks for this. I found it very consoling. I watched a friend die today of a heart attack, on a Zoom call. It was very shocking. I am trying to cope. I appreciate your writings.

Professor Massimo, I'm sending my very best wishes, may you enjoy a wonderful 59th year. Thank you for this thoughtful meditation, for your classes, books, appearances and writings, all of which bring bright and vibrant focus to living each day as fully as possible. You enrich many lives. Cent'Anni !