Here are a few things I learned

Nine modest pearls of wisdom that might be useful moving forward

A few weeks ago I turned 60. One of those entirely arbitrary hallmarks in a human life that nevertheless, despite ourselves, make you look up and pay attention. To celebrate the occasion, my lovely daughter and wife organized a sumptuous dinner in a nice restaurant in Salvador (Bahia, Brazil), where we were staying for a brief vacation. And the celebrations went on a few days later, by way of spending a late evening sipping whiskey at a really cool jazz bar in São Paulo.

Inevitably, I’ve taken the occasion of entering the 7th decade of my life as a good excuse to reflect a bit about what I’ve done so far, what I’d like to do moving forward, and what I’ve learned in the meantime that should inform my future decisions. I hope you will indulge me in this post, which is really a kind of manifesto to myself for how I’d like to live whatever (hopefully long and especially healthy) time is left for me on planet Earth. Who knows, the resulting musings may be useful to others as well.

What I’ve learned

I don’t think I’ve learned much, as it turns out, but perhaps enough. I’m not talking about straightforward knowledge, of which, thanks to multiple stints in graduate school and two academic careers, I have actually accumulated quite a bit, if in very specific fields like plant gene-environment interactions and the philosophy of pseudoscience. I’m talking about wisdom, a department in which, I’m afraid, I’m still woefully deficient.

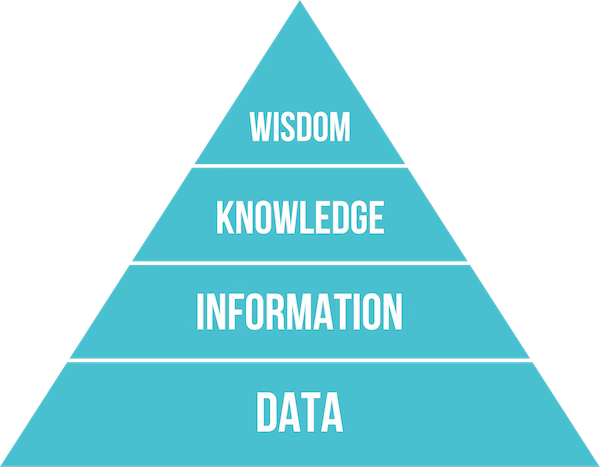

A good way to grasp the difference is by way of the so-called DIKW pyramid, where the acronym stands for: D => data, I => information, K => knowledge, and W => wisdom. The idea is that information depends on data (i.e., facts), knowledge is constructed out of information, and wisdom is derived from knowledge. Reasonable enough, though the tricky part is exactly how one passes from one level of the hierarchy to the next one. Perhaps a more sober and apt way to put it is a poem by T.S. Eliot which is often referenced as the very origin of the idea of a DIKW pyramid in the first place. It goes like this:

Where is the wisdom we have lost in knowledge?

Where is the knowledge we have lost in information?(The Rock, 1934)

Be that as it may, what pearls of wisdom do I think I’ve learned during 60 years of existence? Here are the major ones that come to mind:

(i) There is a fundamental distinction between what falls within my agency and what does not, and my life is always noticeably better whenever I keep this distinction firmly in mind and act accordingly. Which means focusing my efforts on the things that are under my control while developing an attitude of equanimity and acceptance towards everything else.

I’m sure the Stoic-minded among my readers have recognized the source of this: it’s right at the beginning of Epictetus’s Manual for a good life:

“Some things are up to us and some are not. Up to us are judgment, inclination, desire, aversion—in short, whatever is our own doing. Not up to us are our bodies, possessions, reputations, public offices—in short, whatever isn’t our own doing.” (Enchiridion, 1)

(ii) There is another fundamental distinction that is very useful to keep in mind at all times: that between judgments and opinions (which are internally generated by us) and facts or events (which are outside of us). Again, this is Epictetus, a bit further down in the Manual:

“People are troubled not by things but by their judgments about things.” (Enchiridion, 5)

Indeed, Epictetus goes on immediately afterwards: “Death, for example, isn’t frightening, or else Socrates would have thought it so.” If people can disagree about whether death should be frightening or not, then they can disagree about pretty much everything. People can have different opinions about it, but death itself remains a mind-independent fact of life.

(iii) Relationships are by far the most important thing in a human life. There is plenty of good science backing up this insight, but as usual the idea is much, much older:

“Ponder for a long time whether you shall admit a given person to your friendship; but when you have decided to admit him, welcome him with all your heart and soul. Speak as boldly with him as with yourself.” (Seneca, Letter 3.2)

Human beings, the Stoics maintained, are fundamentally social animals capable of reason. From which they inferred that a good human life is one in which we use reason to make this a better world for everyone. And I mean everyone, hence their notion of cosmopolitanism.

Friends are, of course, one of a number of types of relationships that we engage in, and the ancient Greeks had several terms to express in what way we love different people, and even ideas: there is agápē, which means love that comes with an aspect of charity, in the sense of benevolence, embedded into it. This is the sort of love we have for our children, but also for our spouse or partner. Then we have érōs, which in part does mean, as the modern word “erotic” indicates, sexual attraction for someone. However, Plato expanded the concept to indicate, after personal maturation and contemplation, love for beauty itself. There is philía, which describes a sense of affection and regard among equals. Aristotle uses this word to characterize love between friends, for family members, or of community. And finally storgē, meaning affection, especially (but not only) of the kind one has toward parents and children, which includes a component of empathy of the type felt naturally toward one’s children. Storgē was also used to indicate love for a country, or even a sports team, and—interestingly—in situations when one has to put up with unpleasant things, as in the oxymoronic phrase “love for a tyrant.”

However we think of it, love for other people is crucial for a life worth living.

(iv) When people disagree about things, often the disagreement isn’t so much about what it appears to be, but about more basic, unstated assumptions. Consider:

“Imagine arguing with someone about whether a movie is good. This goes on for a while, with both of you quarreling over details. Then it occurs to you to ask: What is a good movie, anyway? What makes one better than another? You realize that you’ve been arguing about a particular movie—the question in the foreground—because you have different opinions about those larger questions in the background. The background questions are what you should be arguing about.” (W. Farnsworth, The Socratic Method, ch. 17)

Yes! You have no idea how much of my life has been wasted debating what Farnsworth, on the basis of Socrates, calls foreground questions, while in fact the real disagreement concerned a background question that both I and my interlocutor had taken for granted and had not even contemplated bringing to the foreground. Need to do better moving forward!

(v) People rarely change their mind because they are confronted with facts. But they do feel very uncomfortable when they are caught contradicting themselves, a situation that generates what psychologists call cognitive dissonance. Again, listen to Farnsworth:

“Socratic questioning typically avoids arguments about external facts. It tries to contradict a claim by using the beliefs of whoever holds it. That’s often wise; confronting people with facts is a surprisingly ineffective way to change their minds about anything.” (The Socratic Method, ch. 18)

When I was a practicing scientist exactly the opposite of this was drilled into the core of my being: present the facts, and people will eventually agree. This isn’t a misconception common only to scientists. The very same mistake underlies the current popularity of “fact checkers,” as if people were prone to change their emotionally entrenched opinions about politics, religion, or even sports just because someone showed them how things really are. Don’t get me wrong: facts are crucial, but they are, on their own, insufficient to persuade those who are emotionally or ideologically committed to an idea. Whatever idea that may be.

The situation changed when I moved from science to philosophy. I thought: ah!, it’s not about having the right facts, it’s about constructing compelling arguments! Nope, it ain’t that either. First off, unless you have a captive audience, like the students in your classroom, most actual conversations are of the back-and-forth variety that simply does not allow one to present a careful argument. Second, and more importantly, my experience is that a lot of people either get pissed off when you out-reason them or, worse, they don’t even realize that they have been out-reasoned!

It took me reading books on rhetoric (like this one, and of course Farnsworth’s) to finally appreciate the point, which was originally understood by Socrates: if you manage to bring people to agree with two or more propositions and then show them that such propositions are in tension with each other, people will pause and start to consider that perhaps they don’t know as much as they thought they did. And that’s the beginning of wisdom, according to the Oracle at Delphi.

(vi) It is far better to ask questions than to lecture people (including my students). This also comes from Socrates, who often begins one of his dialogues (note, dialogues, not lectures) with something along the lines of “Shall we inquire into this, then?” (note the “we,” as well as the “inquire,” very different from “shall I explain this to you?”).

I have realized that my profession has too often led me to engage in lecture-style “conversations” with people, including with friends and family. It’s hard to help it, when you are trained to appreciate the lecture format since the early days of your schooling, and when the very image of a university professor is that of a lecturer.

But asking questions is both more fun, once you get the hang of it, and more ultimately useful. It is fun because good questions are open-ended, so you never know where they may lead. It is more useful because the goal of a conversation shouldn’t be to “win” or to convince the other person of one of your own preconceived notions. It should be first and foremost to understand what and why your interlocutor is thinking, and then to try to find out together (cooperatively, not adversarially) whether there may be something better to be arrived at concerning whatever the subject matter happens to be.

(vii) It is far better to focus on the good that we have rather than on the pursuit of things we don’t have, especially if those pushing us to such pursuit are shallow people or self-interested multinational corporations. Here is how Marcus Aurelius, the emperor-philosopher, puts it:

“Instead of imagining that you possess things you don’t, select, from among those you do have, the ones you count yourself most fortunate to have, and remind yourself in their case how much you’d have wanted them if you didn’t have them. But at the same time take care not to let your pleasure in them get you into the habit of valuing them too highly, to the extent that you’d be upset if you ever lost them.” (Meditations, 7.27)

We live in a society that constantly nudges us back on the hedonic treadmill, telling us that it is crucial for our happiness to have more and newer things. And many of our own friends and family buy, so to speak, into this view of life, with the result that we are continuously judged on the basis of how “successful” we are, with success measured in terms of our careers, the size of our homes, weather we own a nice car or the latest smartphone, and so on.

I’ve been lucky enough to have been able to pursue a career that I find interesting and meaningful, to have people who love me, to live in a great place, and to have people who actually want to read what I write. What the hell do I need a newer iPhone for?

(I’m still working on the last part of Marcus’s passage above, the one about not been too attached to what we have so that we are okay letting them go, when the time comes.)

(viii) The quality of our life is important, not its duration. We hear of billionaires who wish for immortality, even though many people don’t know what to do with themselves come the weekend. I live in a country, the United States, where often doctors are aggressive in their attempts to prolong the lives of their terminal patients, even though all they manage to accomplish is more physical and emotional pain, not to mention sending the families of those patients into bankruptcy. This is what Seneca has to say on the issue:

“No one can have a peaceful life who thinks too much about lengthening it. … Most people ebb and flow in wretchedness between the fear of death and the hardships of life; they are unwilling to live, and yet they do not know how to die.” (Letter 4.4-5)

Of course, other things being equal, I hope to “live long and prosper,” as the Vulcan phrase goes. But that’s the trick, other things being equal. That means physical and especially mental health, without which I’d much rather walk through Epictetus’s open door.

More urgently, it means that I need to redouble efforts to live hic et nunc, here and now, and not to waste time on things that are useless or meaningless. (I’m looking at you, administrative meetings at school!) While I have limited control over my continued health, I most certainly have a lot of control when it comes to cutting down the crap, which by now is a high priority in my life.

(ix) We learn much from those who came before us, if we are willing to pay attention. I grew up with my paternal grandmother and with “uncle Tino,” her companion who was completely unrelated by blood to me. Yet, Tino was a major positive force in my early life. One of the things he insisted on was the appreciation of history, especially the Greco-Roman variety.

But then I became a teenager and I developed an interest for the future, rather than the past. And as a scientist, I certainly had no use for Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, & co.. Until I switched to a career in philosophy, and the very first graduate course I took happened to be on Plato. Shortly thereafter I discovered Stoicism, and particularly Epictetus, and my life has come, satisfyingly, full circle. Uncle Tino was right after all!

Why the ancients? Why pay attention to people (mostly men) who have been dead for a couple of millennia or more? Because they were just like us, and because they thought long and hard about what that means and how to act in order to live a life worth living. Consider:

“There are obstacles in our path; so let us fight, and call to our assistance some helpers. ‘Whom,’ you say, ‘shall I call upon? Shall it be this person or that?’ There is another choice also open to you; you may go to the ancients; for they have the time to help you. We can get assistance not only from the living, but from those of the past.” (Seneca, Letter 52.7)

One of the big advantages of looking at the past is that it is easier to learn from it and then apply those lessons to the present. If we engage, for example, in a discussion about the character of certain contemporary politicians we will likely automatically align ourselves with whatever ideology or party line we happen to prefer, incapable of seeing the flaws in our champion or in their policies.

But if we discuss the concept of leadership, or of government, or of a just society, on the basis of the speeches of Demosthenes against the tyranny of Alexander, or of the writings of Cicero the duties of a citizen, we are less likely to be emotionally impaired in our thinking. Which means we are more likely to learn something, ponder it, and then apply it to contemporary issues and people. (As I try to do here.)

What follows?

Okay, given all the above—those nine pearls of wisdom, such as they are—what are the implications for how I should live my life moving further into decade n. 7? They are probably pretty obvious, at this point, but allow me to spell them out nevertheless:

To begin with, no matter what I do, I better keep in mind Epictetus’s two fundamental distinctions: on the one hand, between what is and is not up to me; on the other hand, between (my) judgments and (external) facts.

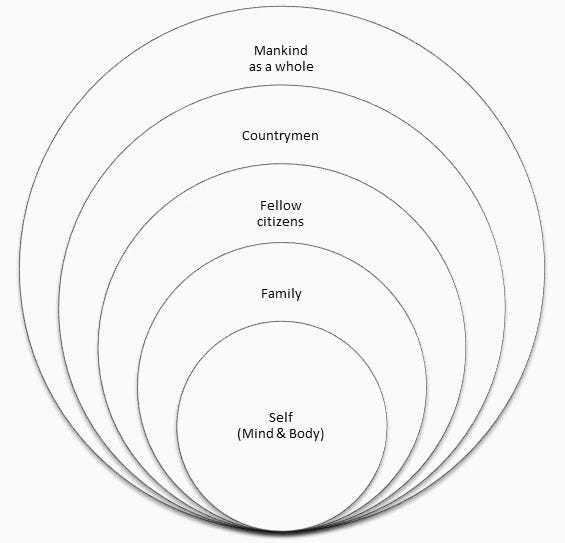

Second, redouble my focus on relationships: with my wife, my daughter, my siblings and the rest of the family, my friends, and further and further out, following a sequence proposed by the second century Stoic ethical teacher Hierocles.

Third, keep in check my innate tendency to lecture and shift as much as possible to Socratic questioning. Also, as a corollary, try to stay away from engaging others directly on hot-button issues (e.g., politics, ideology, religion), because these are usually highly emotional and people don’t respond well to being challenged in their core beliefs.

Instead, and this is the fourth resolution moving forward, attempt to “educate” others in the way I’m educating myself. By thinking about history and ancient philosophy, with the hope that (some) people will then see things better of their own accord, drawing their own conclusions about why, say, Thucydides’s warnings about war and hubris apply to the 21st century CE just as much as they did to the 5th century BCE.

Fifth, and this is a consequence of both the third and forth points, redouble my efforts to teach as well as I can. I am very conscious of the privilege of having access to young minds in my role as a faculty at the City College of New York, and to a broader audience though my writings here at Figs in Winter as well as my books. Simply put, I need to push myself to be worthy of such privilege.

Sixth, it’s good for me to pay attention to what I have, in terms of people as well as material comforts, and nudge my mind away from what I could or even should (according to whom??) have in order to be happy. I already am as happy as a human being is allowed to be by the structure and function of this universe. However, I also know that at some point this all will end for me. It is in the nature of things. Which is all the more reason to focus on the here and now and truly appreciate it.

Finally, it looks like—after having spent years as a scientist and then as a philosopher of science—I have grown up just enough to recognize the wisdom of my uncle Tino about appreciating the ancient Greco-Romans. Which means you can expect a lot more essays in Figs in Winter, and a lot more books on similar topics. Fate permitting, of course.

Better late than never: happy birthday!

Thanks for sharing! Happy birthday!