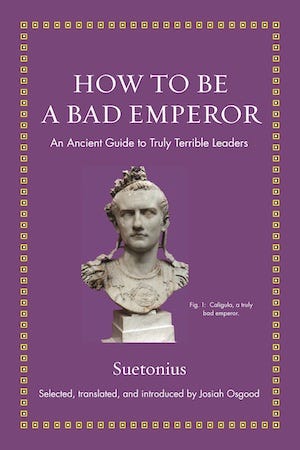

[Based on How to Be a Bad Emperor: An Ancient Guide to Truly Terrible Leaders, by Suetonius, translated by Josiah Osgood. Full book series here.]

We often hear that power corrupts, and that absolute power corrupts absolutely. Don’t need to look further than Suetonius’ The Lives of the Caesars, in part translated anew by Josiah Osgood as How to Be a Bad Emperor, to find ample confirmation. And yet, Suetonius’s perspective was a bit more nuanced: power doesn’t corrupt or ennoble. It simply greatly magnifies what’s already there. Which explains why we can have bad leaders and good leaders, as well as of course a number of mediocre and forgettable ones.

One of the most interesting aspects of Suetonius’s opus is that he didn’t just provide his readers with a rundown of historical events. He wanted them to know about the small and large aspects of his subjects’ characters, because sometimes we learn more from spontaneous private quirks than from carefully orchestrated public behavior.

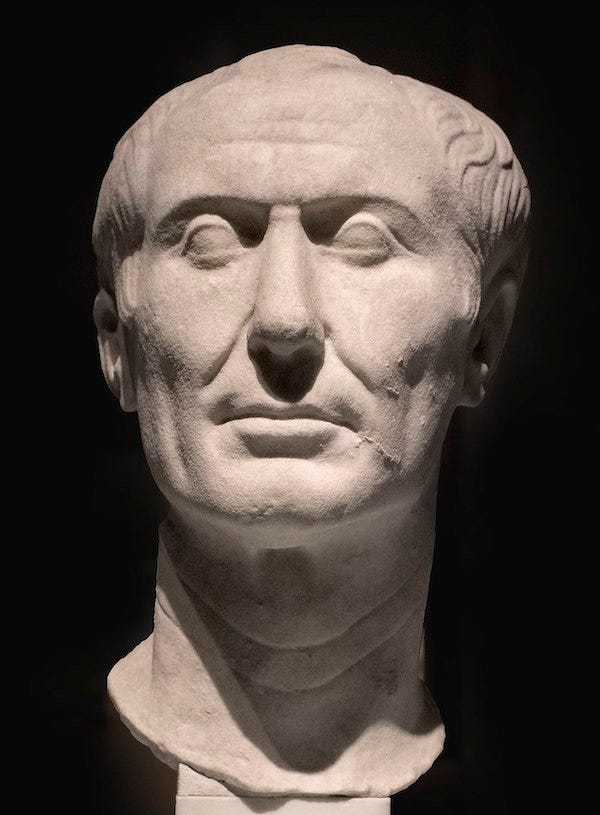

Take for instance the vanity of Julius Caesar—Suetonius’s first emperor, even though technically that title belongs to Caesar’s adopted son, Octavian Augustus. Caesar was terribly concerned with his baldness, and was greatly relieved when he coerced the Senate in allowing him to wear a laurel crown on his head regardless of the occasion. The implication is that we should be wary of vain men (or women) who want to wield great power. They are not likely to use it for the common good. (Reminds you of any recent examples?)

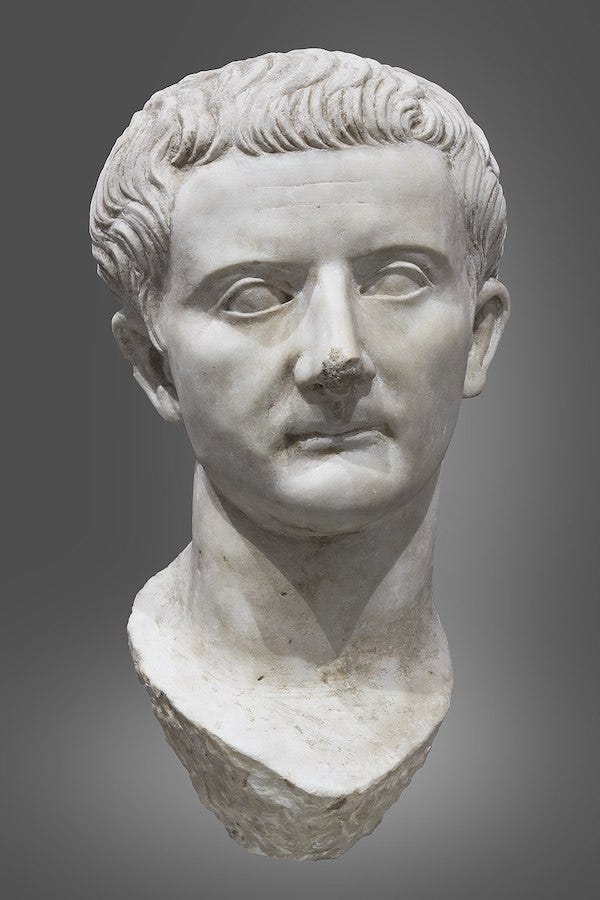

The full original work included twelve rulers, from Julius Caesar to Domitian, but How to Be a Bad Emperor focuses on four: Caesar (100-44 BCE), Tiberius (42 BCE-37 CE), Caligula (12-41 CE), and Nero (37-64 CE). Each biography is organized topically, not chronologically, and Suetonius is not above occasionally reporting rumors, though he usually warns his readers when that is the case. Was Caesar really going to move to Troy and bring all the treasury’s money with him? Who knows. But it was rumored.

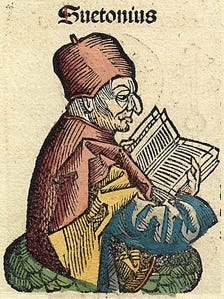

Suetonius belongs to a long tradition of Roman political satirists, but his basic attitude was that our leaders are capable of both great good and great evil, depending on their character. Suetonius himself was, of course, a product of his times. His father belonged to the Equestrian order (the one just below the Senate), and his family was therefore wealthy. His works—unfortunately mostly lost to the sands of time—included titles like Words of Insult and Famous Prostitutes.

Under the emperor Trajan he was appointed advisor on literary affairs and director of Rome’s public libraries (yup, ancient Rome had public libraries!). Suetonius rose even further under the following emperor, Hadrian, becoming secretary of imperial correspondence. However, he became apparently too familiar with the emperor’s wife, which prompted Hadrian to dismiss Suetonius from his post.

Despite the title of Osgood’s translation, obviously this isn’t a manual to forge bad leaders. Quite the contrary, it is meant as a warning that the character of those who lead us is crucial, and we should therefore pay attention to it. I’m sure I don’t have to name names of contemporary politicians to make that point.

Plenty of people have imitated or have been inspired by Suetonius, including Robert Graves in his famous novels abut the emperor Claudius. However, what is most interesting here is not the historical doings of the individuals singled out, but rather what we can learn about leadership in general and how we can apply Suetonius’ lessons to our times. Someone really ought to write a Lives of Modern Politicians…

Here are some highlights from How to Be a Bad Emperor, with accompanying brief commentaries:

[On Julius Caesar] “He accepted excessive honors. … He also allowed honors to be awarded to him that were too great for any human being. … With equal presumption he broke with tradition and arranged the magistrates for several years in advance, gave consular insignia to ten praetors, and admitted into the Senate men who had just been granted citizenship. … Just as outrageous were remarks that he made in public, which Titus Ampius notes: ‘The republic is nothing, a name only, without body or shape.’ … He laughed at Spurinna and accused him of being mistaken: the Ides of March had come without any harm. Spurinna said that while they had indeed come, they had not yet passed.”

Caesar, according to this portrayal, suffered from arrogance, or what the Greeks called hubris. He was so sure of himself and of his own unparalleled power and accomplishments that he did not take seriously ample warnings of a conspiracy against him—even deciding to walk around the Roman Forum without a body guard.

Spurinna was a haruspex who famously had told Caesar to be wary of the Ides of March, and the exchange reported by Suetonius is therefore particularly ironic and poignant.

Julius Caesar was undoubtedly a brilliant man. His abilities as a general rivaled those of the legendary Alexander the Great (to whom, predictably, Caesar often compared himself). He was also a competent and innovative administrator, introducing a new calendar to Rome and embarking in ambitious projects of beautification of the city (parts of Cesar’s Forum still stand in the modern city).

Moreover, his political program of reforms was in fact long due. The two major parties within the Senate, the conservative Optimates (the best men) and the “progressive” Populares (from which the word populism derives) had been battling it out for over a century, vehemently—and sometimes bloodily—disagreeing on various issues, primarily concerned with land reform and redistribution. It was arguably the inflexibility of Optimates like the Stoic Cato the Younger that ultimately led to the downfall of the Republic.

But Caesar was so sure of being exceptionally chosen by the gods (again, sounds familiar?) that he famously crossed the physical and highly symbolic line of the river Rubicon with his army, thus declaring war on Rome and the Senate. He was convinced that he had to destroy the system in order to reform it, and the result was his assassination as well as the end of the Republic and the beginning of Empire.

[On Tiberius] “He at once gave free rein to all of the vices that he had badly concealed for so long. … Because of his excessive fondness for wine he was called ‘Biberius’ instead of Tiberius. … While he swam, he had boys of a tender young age—he called them ‘fishies’—pass between his thighs and make a game of going after him with licks and bites. … It is even reported that once when he was sacrificing, he was so taken by the appearance of the attendant carrying the incense box that he could not stop himself, the moment the ceremony was over, from leading the boy off and raping him, along with his brother, a flute-player. Later, when they jointly reproached him for this appalling deed, he broke their legs. … His nature revealed itself considerably more after he became emperor. … Tiberius committed many cruel and savage deeds, under the guise of strictness and improving morals—but really in keeping with his own nature. … Since by tradition it was forbidden for virgins to be strangled, young girls were first violated by the executioner, then strangled.”

The picture of Tiberius that emerges from these and many other comments by Suetonius is, as far as we can tell, true to life. The contrast with his predecessor, Octavian Augustus, the first Roman emperor, was stark. While Octavian had certainly bent more than one ethical precept before becoming emperor, he did oversee an unusual period of peace and prosperity for Rome. Tiberius, by contrast, was the first one of a series of bad emperors, including his successor, Caligula (more on him in a moment), Claudius (who, despite the friendly treatment in the Graves novels, was no exemplar of virtue), and Nero.

Note in the passages above how Tiberius, like many tyrants, cloaked his misdeeds in the guise of moral language, just like, say, Stalin and Mao would famously do—on a much larger scale—during the 20th century. Beware of self-righteous talk coming from people with uncontested power.

Suetonius doesn’t dwell only on Tiberius’ personal depravity, but notes multiple times how he largely ignored public affairs, thus bringing shame on his office and not really doing much at all on behalf of the Roman people. At least Nero (also more on him shortly) was cuckoo and occasionally cruel, but rebuilt the city with alacrity after the famous fire of 64 CE, which—contra to legend—he didn’t cause (nor did he fiddle while the city was burning, since he was outside Rome at the time).

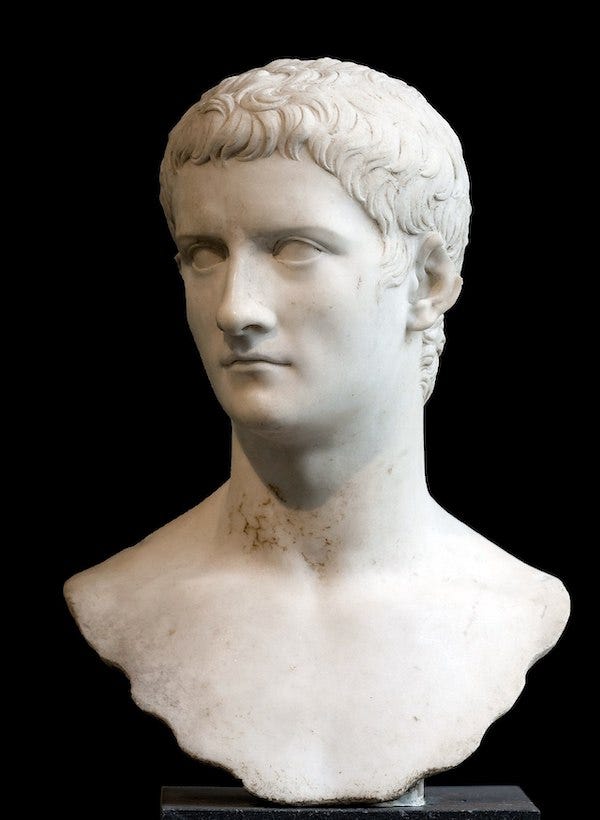

[On Caligula] “Advised that he had risen above the eminence of emperors and kings alike, he began from then on to claim for himself divine majesty. … [He] set up a temple for his own godhead with priests and the most exquisite sacrificial victims. Within the temple stood a golden statue that looked just like him and every day it was dressed in the same outfit that he was wearing. … With all of his sisters he was in the habit of having illicit sexual intercourse. At a crowded party, he placed each of them in turn below him on the couch while his wife was lying on the couch above. … At gladiatorial contests he sometimes would draw back the awnings when the sun was burning most intensely and refuse to let anyone leave. … Sometimes, moreover, he would seal up the granaries and inflict famine on the people. … ‘Remember,’ he said, ‘I can do whatever I want to whomever I want.’ … Whenever he kissed the neck of his wife or girlfriend, he would say: ‘Such a beautiful neck! It will be severed whenever I give the word.’”

Caligula was arguably far worse than Tiberius. While the latter mostly indulged in private debauchery and cruelty, Caligula did so in public and indiscriminately. He seemed to be aware of his damaged character, and possibly of the fact that he became—as some historians have suggested—increasingly mentally disturbed as time went on.

At one point he commented that Seneca, who at the time was at the height of his popularity, was writing at the level of a schoolboy. Posterity is lucky that Caligula was more amused than irritated and didn’t decide to do away with the Stoic philosopher. (Nero did.)

Again we see absurd levels of vanity and hubris, with the difference that Caesar had ample objective evidence of his exceptionality, while Caligula’s accomplishments were in his mind only. Again, does the reference to a golden statue of himself remind you of any recent politician? Caligula, incidentally, was assassinated by his own Praetorian guard, who at one point had had enough of his shenanigans. They designated his uncle, Claudius, as emperor.

[On Nero] “The moment he became emperor, he summoned the lyre-player Terpnus, considered the best at the time, and for days on end sat by him after dinner as he sang late into the night. … He first appeared on stage at Naples and, even when the theater was rocked by an earthquake, did not stop singing until he had finished the song he had begun. … He could not stand being out of the limelight. … His fear and anxiety in competing, his intense jealousy of his rivals, and his dread of the judges can hardly be believed. … After putting up with an emperor like this for just under fourteen years, the world finally abandoned him. … After learning that Galba and the Spanish provinces also had rebelled, he fainted. … Now he urged Sporus to start grieving and wailing, now he begged that somebody would help him to take his life by setting an example. … Then, with the help of his secretary Epaphroditus, he drove a blade in his throat. … He cried at each thing as it happened and kept saying: ‘What an artist dies with me!’”

Epaphroditus, the man who helped Nero commit suicide, was also, incidentally, Epictetus’s master. The general picture that emerges from Suetonius’s treatment of Nero is more pathetic than anything else. Yes, Nero did orchestrate the murder of his own mother, Agrippina, but she was no saint and had actually been plotting against him. He did not burn Rome, and in fact greatly aided first the rescue efforts and then reconstruction. Modern historians agree that the first five years of his reign—under the guidance and tutelage of Seneca and the Prefect of the Praetorian guard, Sextus Afranius Burrus—were a time of peace and prosperity for Rome.

Once more we see vanity coupled with insecurity, the latter reaching pathological levels evident in many of Nero’s actions. Ultimately, he didn’t really want to be emperor, he wanted to be an artist, and regretted that he hadn’t been able to orchestrate a better exit from himself.

After Nero died the empire briefly descended into chaos, with four emperors succeeding each other within the span of a single year: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, and Vespasian. The latter managed to establish a new dynasty and to build what we now know as the Colosseum. The last two Caesars about which Suetonius writes are his sons: Titus and Domitian—the second being the very same who sent Epictetus into exile. But that’s a story for another time.

[Next in this series: How to win an election with Quintus T. Cicero. Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX.]

Well put Massimo, one small nit pick: several times you use the word "weary" when you mean "wary" (I should have been a Homonym Controller rather than an Emperor!). Thanks for reviewing this series. One question: Do you think that the idea of selectively using parts of the texts is in general a good idea as they do in the series?

I missed this when first posted, but my wife (happily) advised me to go back and read it. My conclusion: our former president had some of the impressive elements of the greatest leaders of all time. Seriously--very interesting stuff. Thanks, Massimo.