[Based on How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life, by Seneca, translated by James S. Romm. Full book series here.]

Author Michael Pollan said in an article in The New Yorker [1] that some who take psychedelic drugs report to have “stared directly at death … in a kind of dress rehearsal.” If you are concerned about (or fascinated by) death you could try that. Or you could practice Stoic philosophy, especially under the guidance of Seneca the Younger.

How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life collects extracts from eight works by Seneca in which he touches on the issue of death, an issue that seems to never be too far from his mind, as translator James Romm (author of an excellent biography of the Roman philosopher) points out. Seneca did not write a single treaty on the topic, as he did on anger. Rather, he touched on it in a number of his writings. Because death can come at any time, and in a real sense we are dying every day, since the very moment we are born.

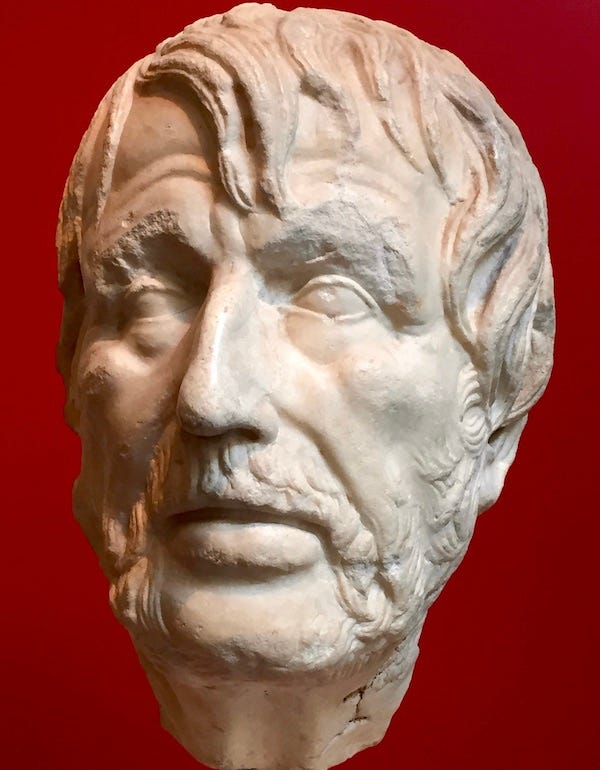

Seneca knew something of death lurking behind the corner. He was a young senator under the mad emperor Caligula. He was then condemned to death—on specious charges—under the following emperor, Claudius, though the sentence was commuted to exile in Corsica, where he stayed eight years. Then he was given the near impossible task of tutoring and guiding the young Nero, who soon became himself murderously deranged. Eventually, Nero accused Seneca of being part of a conspiracy against him and ordered the philosopher to commit suicide. Seneca was 69, the same age as Socrates when he also was put to death unjustly, by a democratic assembly rather than a capricious tyrant.

The Stoics thought that virtue—meaning prosocial behavior in the service of the human cosmopolis—was the only true good in life. That’s because everything else, including health, wealth, reputation, career, relationships, and so forth, can only be used properly if one acts virtuously. Otherwise all those externals become a source of evil.

Consider, for instance, wealth. Nero was the wealthiest man in the empire, and so it was up to him whether to use his considerable means to make people’s lives better or to turn them into a nightmare. The choice rested on his character, which unfortunately left much to be desired.

Death is the termination of life as we know it, and life itself belongs to the class of what the Stoics called adiaphora, usually translated as “indifferents.” The word doesn’t mean that we don’t care, it’s just that adiaphora literally make no difference to the only thing that matters: virtue.

Life itself can be preferred or dispreferred. It is preferred if one still has enough energy to do some good in the world. Dispreferred if one is a tyrant. Or simply too old and frail to want to continue existing. The Stoics would have most definitely been in favor of what we call assisted suicide. Indeed, Epictetus, in Discourses 2.15, rushes to the side of a friend in order to help him carry out his decision to leave this world [2].

It is interesting, and perhaps a bit sad, that—largely under the nefarious influence of two millennia of Christianity—we are still immersed in a heated debate about the “sanctity” of life and the very permissibility of suicide. Seneca, rightly, would be very perplexed by the continuation of such debate.

However it will happen, death will come. And it will be, as Seneca says, the ultimate test of our character. It makes sense, therefore, that we devote thought and effort to getting ready. We don’t know when and how it will take place, only that it definitely will.

Here are some highlights from How to Die, with accompanying brief commentaries:

“Whatever existed before us was death. What does it matter whether you cease to be, or never begin? The outcome of either is just this, that you don’t exist.” (Epistle 114.27)

Seneca here is reminding his friend Lucilius of the famous symmetry argument advanced by the Epicureans: we are so worried about not existing for eons after we die, and yet we are not bothered a bit by the fact that we did not exist for eons before we were born. What’s the difference? Not one of fact, because the two situations are exactly symmetrical, but only one of human awareness and judgment: we didn’t know that we were not born before coming into this life, but we now know that we’ll have to leave. And we judge this to be a bad thing.

As I pointed out when discussing Epictetus’ version of Stoicism, one of the fundamental precepts of our philosophy is the recognition of the distinction between objective descriptions of the world and subjective human judgments. Epictetus reminds us (Enchiridion 5a) that it is not things that disturb us, but our opinions about things. And while it often is not in our power to change things, we can certainly change our opinions bout them.

Death is an obvious case in point. We cannot change the objective fact that we have not existed for long time before being born, and that, symmetrically, we will not exist for a long time after we die. But we can alter our judgment of these facts, recognize their similarity, and focus on enjoying as much as possible the interval between those two eons of oblivion, while it lasts.

“Consider that the dead are afflicted by no ills, and that those things that render the underworld a source of terror are mere fables. No shadows loom over the dead, nor prisons, nor rivers blazing with fire, nor the waters of oblivion; there are no trials, no defendants, no tyrants reigning a second time in that place of unchained freedom. The poets have devised these things for sport, and have troubled our minds with empty terrors.” (To Marcia 19.4)

Another one of my favorite passages from Seneca. Poets (and priests!) have made up all sorts of awful tales about the afterlife, either for entertainment (“sport”) or in order to manipulate us. But that’s all they are: made up stories reflecting human fears and hopes, not the reality of things.

So let us not waste time and emotional resources wondering about what awaits us “after.” There is no after (though, to be fair, Seneca was agnostic on this point), there is only here and now. Again, the Stoic interest in death is often misunderstood as a type of morbidity, yet it is anything but. The point that Seneca and other Stoic writers keep stressing is that awareness of the inevitability and unpredictability of death ought to spur us to focus on the current moment and to try to live it for all its worth it. Do not postpone important things until tomorrow, because there may be no tomorrow. Do not wait to show your loved ones that you care for them, because there may not be another chance.

“Just as with storytelling, so with life: it’s important how well it is done, not how long. It doesn’t matter at what point you call a halt. Stop wherever you like; only put a good closer on it.” (Epistle 77.5-20)

We are constantly told that the longer we live the better. We celebrate people who reach late age, especially if they approach the mythical 100 years. We are so impressed! But by what, exactly? Why are we not curious, instead, about how people live their lives? As Seneca puts it elsewhere, to live is no impressive feat, every living organism does it. To live well, by contrast, is only within the grasp of a mindful human being.

One of the reasons I like reading biographies of interesting people is because they remind me of what a good human life looks like. For instance, I am currently reading Andrew Roberts’ biography of Churchill, whose reputation throughout his life went through a series of dramatic ups and down, and yet who did his most important and consequential work—as Prime Minister of the UK during WWII—when everyone thought he was done for good and his life was over.

Or consider Cicero, whose life similarly was a public and private rollercoaster, and yet managed to write eleven of his twelve books on philosophy in the last four years of his life, when he was in his 60’s, just before he was murdered on the order of Mark Anthony. And we still read those books over two millennia later!

I don’t aspire to be a Churchill or a Cicero—that would set the bar too high. But I do take great consolation from the thought that it is up to me whether to spend my time on earth in a meaningful manner (notice that I didn’t say “productive,” with his capitalist/consumerist overtones) or not. By reading this essay, you are literally contributing to the meaning of my life. Thank you.

“Anywhere you cast your glance, the end of your troubles can be found. You see that high, steep place? From there comes the descent to freedom. You see that sea, that river, that well? Freedom lies there, at its bottom. You see that short, gnarled, unhappy tree? Freedom hangs from it. Look to your own neck, your windpipe, your heart; these are the paths out of slavery. Are these exits I show you too laborious, demanding of resolve and strength? Then, if you ask what is the path to freedom, I say: any vein in your body.” (On Anger 3.15.3)

This brings us back to the delicate issue of suicide. What Epictetus called “the open door” is always available to us, if we feel that we cannot take it anymore, and it is that option that—for the Stoics—is ultimate the root of our freedom.

Nobody can force us to do anything precisely because the door remains open and it is in our power to walk through it, by any of the various means that Seneca lists in the above passage. It’s interesting that we have sayings like “well, I couldn’t help it, he pointed a gun to my head.” Yes, you could have helped it, would respond both Seneca and Epictetus. Your yielding to the threat of a gun just means that you value your life more than whatever the guy who was threatening you wanted you to do. Understandable, but let’s tell it like it actually is.

I get that suicide is a very complex issue. We do not want to encourage, say, teenagers with a crushed love interest to walk through the open door. And we don’t want people who are affected by mental conditions like depression and anxiety to do it either, if they can still be helped. But that’s not at all what the Stoics were talking about. They were concerned with the preservation of human dignity, pointing out that sometimes the only way to achieve that goal is to “slip the cable,” as Seneca says in one of his letters to Lucilius (n. 70).

When our pets are condemned to experience continuous and never-ending pain at the end of their lives we speak of intervening “humanely” so that they will no longer suffer. And yet most states in the US and most nations in the world still deny that very same opportunity to actual human beings.

“So should I fear earthquakes, when an excess of saliva can choke me? Should I dread waves roused from the sea’s depths, or worry that a flood tide, drawing up more water than usual, will sweep in, when a drink that goes down the wrong way has killed men off by suffocation? How foolish, to fear the sea, when you know that a droplet can destroy you!” (Natural Questions 6.1.1.2-9)

We are worried not just about death per se, but also about the manner in which we’ll die. Indeed, arguably more about the latter than the former. I sympathize. But Seneca is, once again, right. Death can come suddenly from the most unexpected direction, and it’s usually not up to us to decide when and how (with the exception of the above mentioned open door, of course).

To be sure, this is no counsel for recklessness. Seneca is not advising us to seek dangerous situations on purpose just because. He is however reminding us that our death, even if the process should turn out to be relatively extended, will be but a fraction of our existence. So why obsess so much about it, and risk not enjoying what we have right here, right now?

The title of this Substack is Figs in Winter. It comes from a phrase of Epictetus (in Discourses 3.24.87) that reminds us not to be fools, not to wish for figs in winter—or friends and relatives when they are gone—but rather to enjoy them during the summer, the season that Nature has allotted to them. Carpe diem, pluck the fruit of the day, as the Epicurean Horace famously put it.

_____

[1] 9 February 2015.

[2] Later in that episode Epictetus discovers that his friend did not have a good reason to die and chides him on his casual approach to death. Which makes the point that the Stoics did endorse suicide, but only when actually warranted.

[Next in this series: How to tell a story with Aristotle. Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V, VI.]

Dying is easy if often unpleasant. Staying alive is trickier.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XfwQ_7xqO7Y

Brilliant as usual, thank you Massimo