[Based on How to Grieve: An Ancient Guide to the Lost Art of Consolation, by Pseudo-Cicero, translated by Michael Fontaine. Full book series here.]

In 63 BCE Marcus Tullius Cicero was on top of the world. He was elected Consul, the highest political office in the Roman Republic, and he used the power of his office to thwart the Catiline conspiracy against the State. He was acclaimed Father of the Nation.

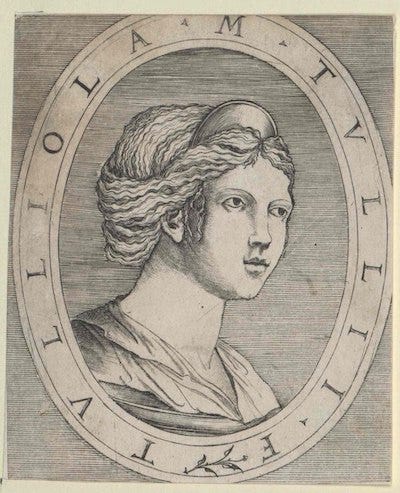

A mere five years later, he found himself exiled and on the run, his property destroyed or confiscated, his life constantly in peril. And it only got worse: in 45 BCE his beloved daughter Tullia died of childbirth at 32. He was politically finished (or so he thought) and his personal life had been dealt the worst blow a parent could receive.

The problem, as he knew very well, was Fortune. It is both fickle and outside of our control. It can bring someone to unimaginable heights or plunge them into equally inconceivable depths. And grieving people such as himself need help, as he wrote in his Tusculan Disputations:

“People whose grief is so great that they’re falling to pieces and can’t hold together should be supported by all kinds of assistance. That’s why the Stoics think grief is called lupe, since it’s a ‘dissolution’ of the whole person.” (3.61)

Cicero was distraught and depressed. But he was a philosopher. He figured that philosophy was the way out. So he wrote a self-consolation essay, trying to argue himself out of his state of misery. As he put it:

“I hacked Nature and talked myself out of depression.” (Tusculan Disputations, 4.63)

We are nowadays familiar with the genre of philosophical self-consolation, from Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations to Boethius’s The Consolation of Philosophy to Augustine’s Confessions. And of course consoling others by philosophical means was a well established practice. But Cicero was the first one to turn the practice on himself, in an early version of what we today call cognitive behavioral therapy: change your thoughts and behaviors, and you will change your emotions.

Tullia Ciceronis was born in 78 BCE and did not live an easy life. She became a widow at age 20, remarried two years later, divorced, and married again at age 27. Unfortunately, her husband Publius Cornelius Dolabella—whom Cicero had disapproved of—turned out to be a rascal and the marriage was a disaster. She got pregnant but gave birth to a boy who did not survive. She herself died of complications the following months.

Tullia bore all this with strength and resilience, and Cicero regarded her as what the Christians would have called a saint, though Cicero’s philosophy was a version of Platonism and had nothing to do with the Judeo-Christian tradition.

Translator Michael Fontaine reminds us of a quip by American psychiatrist Peter Breggin, who said that “Stoicism is a philosophy for someone going down in an airplane.” Since Cicero was going down in a metaphorical airplane, he turned to Stoicism in particular, and Greco-Roman philosophy more generally, to ready himself for the impact.

He began with reading what other philosophers had written about grief and bereavement. In his time the now well known writings of Seneca and Plutarch were not yet available, so he turned to the Platonist Crantor of Soli, whose treatise on the subject is now unfortunately lost. As Fontaine aptly summarizes the difference between the ancient and modern approaches to grief:

“Grieving today is collective and often analyzed as a series of stages. For Crantor, as for the Stoics who refined his ideas, it is a matter of individuals finding the inner strength to accept reality. …Others have survived it before us, which means we can, too. Resilience, endurance, and individual effort, therefore, are the way forward.” (p. xvii)

The result of Cicero’s reflections was one of the masterpieces of the ancient world, Consolatio (Consolation). The problem is: it has been lost to the sands of time. Wait, so what exactly has Michael Fontaine translated and turned into Princeton Press’s How to Grieve, part of their Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series?

Here is where things get intriguing. The last traces we have of the original Consolatio date back to the fourth century of the modern era. After that, nothing is known of it until 1583, when copies of the book started circulating in Venice. The text of the Renaissance version did contain all the known fragments of the original, plus a number of similarities with other known works by Cicero, particularly the Tusculan Disputations, where he does talk about grief. Moreover, the writing style is undoubtedly Ciceronian.

From the beginning, though, people were skeptical of the authenticity of the newly rediscovered Consolatio, often attributing authorship to an Italian Renaissance scholar, Carlo Sigonio. Fontaine does not buy the Sigonio theory, though he thinks that the Italian did know who was responsible for the reappearance of the book.

Despite lingering doubts, Consolatio was included for centuries in published collections of Cicero’s work, albeit with a note of caution. Then in 1999 a stylometric analysis was performed via computer. It looked, explains Fontaine, at “the relative frequency across a range of texts of ‘function’ words, like et (and) or in (in) or est (is), to determine authenticity.”

The result was that the book is not authentic. Fontaine points out that, rather amazingly, in four centuries of scholarship nobody had bothered to check a block quote that the alleged Consolatio attributes to Plato. When Fontaine did, he discovered that it was actually by Marsilio Ficino’s Life of Plato, published in 1477, a dead give away!

Case closed, then. So why am I writing this essay, and—more to the point—why did Fontaine bother to translate the Pseudo-Ciceronian Consolatio in the first place? I’ll let him answer directly:

“Not all fakes are fake in the same way. This fake is not a fabrication, but a recreation. It is Cicero refined and distilled and concentrated. Some parts are taken almost verbatim from Cicero’s other works, and his spirit and thought infuse the entire text. Not a word is inconsistent with his philosophy. (p. xx)

So even though I refer to the author of Consolatio as “Pseudo-Cicero,” it is well worth taking seriously the philosophical advice the author gives us about how to deal with one of the most profound and devastating of human emotions.

Here are some highlights from How to Grieve, with accompanying brief commentaries:

“I have to try—if there’s any possible way—to fix myself, and stop my world from caving in. I mean, if I always counseled others when it hit, then why not myself? And if I’ve absorbed horrors that human strength was powerless to avoid or avert, then why not—if I possibly can—use reason to relieve them?” (Preamble)

This is a good summary of the Greco-Roman approach to things, so different from our modern one, unless we practice something like cognitive behavioral therapy. Nowadays we are told that grief is natural (it is) and that we just have to let it play out (we don’t). We are also taught, as mentioned above, that grief can be collective, that it has stages (turns out that’s not really true), and so forth.

The Greco-Romans agreed that grief is natural, but not that it needs to be left alone. Indeed, they saw a danger in wallowing in grief, in coming to define ourselves by grief. Moreover, they thought that grief is always personal and needs to be tackled by the individual. However, they did agree that there is a supra-individual component to it: if we grieve too long or too deeply then we hamper our functioning in society. In a sense, excessive or prolonged grief becomes a form of egotism or even narcissism, and we need to do something about it.

That is why Seneca, for instance, writes in his letter to Marcia, who has lost an adult son, that he feels compelled to intervene because she has been grieving for three years (1.7) and risks permanently neglecting her other sons, her husband, and society at large (2.5).

Pseudo-Cicero reminds me of Epictetus (Enchiridion 26) when he says that when something bad happens to others we are ready to comfort them by putting things in perspective, but when our turn comes it’s “oh, poor wretch that I am.” The right attitude, rather, is a combination of the two: yes, let us acknowledge the devastating effect of losing a loved one, especially one’s child. But let us also use reason and experience (i.e., wisdom) to keep things in perspective and remind ourselves that death is natural, and that we still need to carry on because we have duties toward our fellow human beings.

“I can affirm that in the years I dedicated to improving or enhancing my country, I did truly live. And, if I had the power to extend my life, nothing could persuade me to live longer than the pursuit and cultivation of the common good, since that is the single most glorious and praiseworthy project for a human being.” (The stages of life)

One way to deal with adversity—confirmed by modern scientific research—is to redirect our attention to alternative meaningful pursuits. Relationships, like those we have with our children, our partners, or our friends, are indeed among the most meaningful and enriching components of our lives.

But as Pseudo-Cicero reminds us here, laboring for the good of the polis is an excellent way to focus one’s energies and derive meaning from what one does. Few people have the opportunity to become Consuls in the Roman Republic or its modern equivalent (say, President of the United States). But we all have opportunities to make this a better world, if we put our minds to it.

That is, of course, why we hear so often of people who lose their children to a tragedy—be it a natural one like cancer or a human made one like a shooting—and use their grief as a positive engine of change, devoting time and energy to publicly advocate in order to reduce the chance that others will have to go through what they have been through.

“Death either obliterates all consciousness, or it transports us to some other place. If death extinguishes consciousness, if our passing is like the rare, dreamless sleep that brings complete and total relaxation, then—well, what a deal dying is! … If we’d rather death be a moving on to the regions where the departed dwell, then what could be more enviable than reuniting in death with those you loved in life?” (What happens after death)

Pseudo-Cicero lays out the very same two options, and in very similar terms, that Socrates considers in Plato’s Phaedo: either death is like a dreamless sleep from which we never awake, or it is the beginning of a new life. Either way, it’s a win!

Both Pseudo-Cicero and the real Cicero—like Socrates before them—lean toward the notion that there is, in fact, an afterlife. Cicero was, after all, a Platonist, albeit of the skeptical variety, so he believed in the immortality of the soul and the existence of a transcendental reality (the famous realm of Ideas that we can access while alive if we philosophically manage to get out of the Cave).

I cannot afford any such belief, I’m afraid. It goes against my understanding of the scientific image of the world, which I think leaves no room for souls, afterlife, and other such comforting but ultimately entirely unsubstantiated notions. That’s okay, an endless dreamless sleep really isn’t such a bad bargain. Besides, it ain’t in my power to bargain with Nature anyway!

“All excessive grief is disgraceful and unnatural because grieving excessively and unreasonably is a conscious choice.” (Excessive grief is disgraceful and misguided)

This may sound rather distasteful to our modern, perhaps overly delicate sensibilities. But Pseudo-Cicero is making a fundamental point here: our emotions are, to an extent, the result of our choices. And we can consciously change them.

That’s the whole point of cognitive behavioral therapy, which began in the late 1950s with Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck, who were both inspired directly by Stoicism, and specifically by Epictetus. As the latter famously put it, “People are troubled not by things but by their judgments about things. Death, for example, isn’t frightening, or else Socrates would have thought it so.” (Enchiridion 5a)

The modern view in cognitive science is congruent with Stoic psychology: certain proto-emotional reactions, like a sudden feeling of imminent danger if we hear a loud and unfamiliar noise, are automatic and cannot be avoided. But once an emotion—like fear—is fully formed it includes a cognitive component, along the lines of: “I should be afraid because that noise means someone is going to kill me!” If we move from proto- to fully formed emotions in part by telling ourselves a story then it stands to reason that we can counter that story with a better and more productive one.

So “excessive” grief, like any other excessive emotional reaction—anger, for instance—is indeed the result of conscious choices, and they can be consciously countered. Remember that the next time you’re tempted to say something like “I can’t help it, I just feel that way.”

“Consider that brave and glorious remark of Cornelia’s. She’d already lost twelve children when she saw her sons Tiberius and Gaius assassinated. Instead of getting paralyzed by fear or traumatized by grief, she said, ‘I would never call myself unhappy: I bore the Gracchi!’” (On manfulness in women)

The courageous example of Cornelia, mother of the Gracchi, is taught still today in elementary school in Italy. She was an example of Roman virtue, integrity of character, and fortitude in the face of extreme adversity. What is interesting here is that Pseudo-Cicero devotes a substantive section to examples of courageous women who have dealt with grief in a “manly,” meaning virtuous, manner. (Remember that the Latin word for virtue is vir, which means man; though it is actually a translation of the gender neutral Greek arete, meaning excellence.)

We are told, among others, of the women of Sparta, who checked the bodies of their dead sons when brought back from a military campaign. If they found wounds in the front, the mothers would lead the funeral procession. But if they found wounds in the back—indicating that the individual had been killed while running from the enemy—they would turn away and have the remains buried in secret.

These examples should not be surprising, as the Stoics explicitly stated on multiple occasions that in their opinion women were just as capable as men to be virtuous and even to study and practice philosophy. We find a similar egalitarian attitude in both Plato’s Republic and the teachings of Epicurus, the Cynics, and the Cyrenaics. It is therefore disheartening to still hear today, over two millennia later, that women are somehow not a match for man’s courage and ability to withstand pain.

[Next in this series: How to die with Seneca. Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V.]

An excellent and thought provoking piece ! Very relevant to the hear and now of my life and the worlds

So clear, so practical, so persuasive - AND helpful to me today! Thank you, Massimo - again!