νέα ἐϕ’ ἡμέρῃ ϕρονέοντϵς

(Thinking new thoughts every day)

—Democritus, 5th century BCE

Turns out, the word “innovation” ain’t new at all. It’s earliest known use is in Greek (of course): kainotomia, and is found in a fifth century BCE comic play by Aristophanes. Funny, since the Greeks are often (and falsely) said not to have been innovators.

Armand D’Angour, the translator of How to Innovate, reminds us that, actually, the Greeks invented the alphabet (borrowing and adapting from earlier attempts by the Phoenicians), philosophy, logic, rhetoric, mathematical proofs, theatrical drama, rational medicine, monetary coinage, lifelike sculpture, competitive athletics, architectural standards, self-governing city states, and democracy. Not bad, yeah?

In fact, the Greeks also attempted to understand what makes innovation possible in the first place. In particular, Aristotle (384-322 BCE) was the first to analyze the logic of change itself. In Book 1 of his Physics he starts out by refuting Parmenides’s notion that change is illusory because it is metaphysically impossible. He then arrives at the conclusion that the new is hardly ever completely new, but depends in complex ways on the old. In Book 2 of Politics, Aristotle then tackles change at the political level, aiming to discover the best way to organize a society, or polis.

Two millennia later the thinkers of the Renaissance began their own quest for innovation by going back to the classics, recreating and adapting ideas about music, art, and science that were originally developed by the Greeks.

How to Innovate explores what Aristotle has to say about innovation in Physics and Politics, adding a selection of shorter texts on specific examples. One concerns the construction of the famous Syracusia, a giant battleship that prompted Archimedes to discover the principle of buoyancy. (Think Eureka!, Eureka!) A second example focuses on the contrarian strategy deployed by the Theban general Epaminondas at the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE. And the last example details a competition for the invention of new weapons set up by the Syracusan tyrant Dionysius I, which resulted in the invention of the catapult.

The following are some highlights from How to Innovate, with accompanying brief commentaries:

“The earliest philosophers were misled in their search for truth and the nature of things by their naive outlook, which led them down a blind alley. They claimed that nothing can either come to be or cease to be, on the grounds that what comes to be must do so either from what is or from what is not. In their view neither of these is possible, since on the one hand what exists cannot come into existence because it already exists, and on the other nothing can come into existence from nothing—there must be something preexistent.” (Aristotle, Physics, 1)

Here Aristotle summarizes Parmenides’s argument against the very possibility of change. He then goes on to discuss a number of examples that contradict Parmenides. For instance, animals come from animals, and animals of particular kinds—say, dogs—come from animals of particular kinds. This is possible because the resulting creature already has the property of being an animal, a property that does not come out of nowhere. And yet, it is the property that pre-exists, not the specific animal, that is, the dog. Aristotle did’t know anything about genetics, but he was describing a process of becoming that is made possible by the laws of inheritance.

From a modern perspective it is interesting to ask how Aristotle—or, for that matter, Parmenides—would have accounted for evolution, a possibility that had actually been raised (though, obviously, not in Darwinian terms) by the Presocratic philosophers Anaximander and Empedocles.

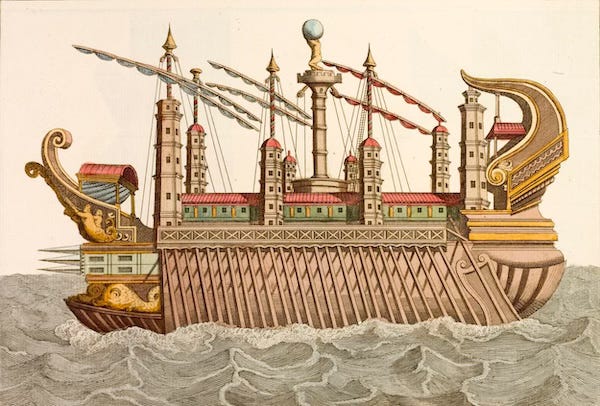

“The construction of the ship built by Hieron of Syracuse, overseen by the mathematician Archimedes, is worthy of commemoration. … The material for its construction was wood procured from Etna, in sufficient quantity for the building of sixty quadriremes. … It was only by constructing a screw windlass, which was an invention of Archimedes, that it was possible to move a hull of such enormous size down to the sea. … The ship was constructed to hold twenty banks of rowers and had three decks. … All the cabins had a mosaic floors made from a variety of stones, arranged to amazing effect to depict the whole story of the Iliad. … The uppermost deck contained a gymnasium, and boardwalks in proportion to the size of the ship, in which were planted colorful flowerbeds brimming with flowers, which were watered by concealed lead piping. … Adjoining these was a six-square-meter temple to Aphrodite, with a floor made of agate and other precious stones from Sicily. … Adjoining the temple to Aphrodite was a ten-square-meter library with walls and doors made of boxwood, containing a collection of books.” (Athenaeus of Naucratis, The Learned Banqueters, Book 5)

This is only a very partial description of the Syracusia, which must have been an incredible spectacle to behold. It had a complement of 800 men and there was only one other port, other than Syracuse’s, that could host it: Alexandria, in Egypt. Which is why Hieron sent the ship as a gift to King Ptolemy.

Archimedes is credited with a number of inventions and discoveries connected to the design and construction of the Syracusia, which makes the more general point that innovation is often spurred by necessity. The ship, on the orders of Hieron, had to be built. It was up to Archimedes and his engineers to figure out how.

For some reason, this reminds me of the frequent quote from Scotty of the original Star Trek series: “I can’t change the laws of physics, Captain!” And yet, somehow, both Scotty and Archimedes got it done.

“On the Theban side Epaminondas, by employing an unusual disposition of his own devising, managed through a unique strategy to achieve his famous victory. From the whole force he selected the strongest men and stationed them on one wing, intending to fight to the end alongside them. The weakest he placed on the other wing and instructed them to avoid engaging and to withdraw bit by bit as the enemy advanced. By arranging his phalanx in oblique formation, therefore, he planned so that the battle should be decided by the elite fighting wing.” (Diodorus, Library, 15)

Epaminondas was a legendary Theban general who achieved what was hitherto thought impossible: defeating the Spartans, thus inaugurating a period of political and military dominance for Thebes.

During the battle, the Spartans, confident of their own valor and ability, deployed the then standard strategy, advancing both of their wings simultaneously and maintaining them opposite the Theban wings. Epaminondas’s unorthodox strategy gave the Spartans a false sense of security, as they saw one enemy wing slowly but surely retreat in front of them.

Slowly the Thebans deployed on the strong wing began to get the upper hand on their side, after which they suddenly reinforced the weak wing, catching the Spartans by surprise. The Peloponnesians started to fall by great numbers, as Diodorus tells us. The Spartan king, Cleombrotus, fought valiantly, but sustained a number of wounds and died in battle. Without a leader, the Spartans, stunningly, were routed. They lost four thousand men, against only 400 Thebans. Sometimes, you have to have the guts to disrupt things and try something risky and new in order to win a battle!

“Dionysius rapidly gathered together skilled workmen from the cities under his control and enticed them with high pay from Italy and Greece as well as from Carthaginian territories. … The Syracusans took up Dionysius’s project with enthusiasm, and they competed strenuously to manufacture weapons. … And in fact it was at this period, with the most skilled craftsmen being concentrated in one place, that the catapult was invented in Syracuse.” (Diodorus, History, 14)

Dionysius I of Syracuse was one of the first to understand a principle that is still applied today: if you want something new to be developed a good strategy is to organize a competition among a bunch of creative people and put out a prize for the winner.

It worked in the case of the invention of the catapult, which contributed to making Syracuse a major power in the Mediterranean, and also led to the deployment of new ships characterized by four and five hulls, a first in the ancient world.

It was because of innovative approaches like those that led to the catapult and to the Syracusia that the city of Syracuse was able to play an outsized role in the history of Magna Grecia from the Peloponnesian War (415-413 BCE in Sicily) to the final conquest by the Romans in 212 BCE, during which Archimedes lost his life.

[Next in this series: How to Stop a Conspiracy, by Sallust. Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI.]

So, here was me having faith in Ecclesiastes 1:9 as true through and through, but no-- Seriously, interesting and (for us not classical scholars) revealing account. Now if the Greeks had just shown us the way to safeguarding democratic society/government. Thanks, Massimo Pigliucci. And Aristotle.