How to keep an open mind with Sextus Empiricus

Part II of the Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series

[Based on How to Keep an Open Mind: An Ancient Guide to Thinking Like a Skeptic, by Sextus Empiricus, translated by Richard Bett. Full book series here.]

What do you know? Not much, and you?

That was the tagline of a Public Radio International comedy quiz show that ran for three decades hosted by Michael Feldman (and which is now a podcast, of course). But it could just as well describe the skeptical philosophy known as Pyrrhonism.

Named after Pyrrho of Elis (360-270 BCE), Pyrrhonism was the original western version of Skepticism. Unfortunately for us, Pyrrho apparently never wrote anything. His student, Timon of Phlius, did, but most of his works are now lost. As a result, one of our major sources on the whole philosophy is Sextus Empiricus (late second and early third century), the author of the famous Outlines of Pyrrhonism, which has been translated into modern language by Richard Bett for Princeton University Press’ ongoing Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series.

The essence of Pyrrhonism is that our unhappiness is rooted in the fact that we are too attached to all sorts of opinions we have no business being attached to, because they are about “non-evident” matters, i.e., broadly and imprecisely speaking, matters that are not obvious to the senses (like: it’s day now!) or to basic reasoning (like: 2+2=4). One example might be any broad statement about what does or does not make people happy. (Did you catch the irony?)

The goal of life, for the Pyrrhonists, is ataraxia, that is, tranquillity. And the way to achieve it is epoché, or suspension of judgment. Phenomenologically speaking, they had a point. Tranquillity is indeed pleasurable, and many of us would rather be serene than anxious or angry or whatever. And it is also arguably the case that holding on to strong opinions about non-evident matters—say, in politics, or ethics, or metaphysics—is likely to cause us headaches and a general movement away from ataraxia.

In order to avoid this, Sextus and his fellow Pyrrhonists devised a series of techniques to make sure, as Bett says in his introduction to the book, that we never accept anything put forth by someone who thinks he understands how the world works. That’s what the Outlines is largely about.

Interestingly, Sextus’ life is shrouded in mystery. We know only that he was active around 200 CE and that he was a medical doctor, member of a dominant school at the time known as the Empirical school. But we don’t know anything about his personal life, not even where he came from or where he lived.

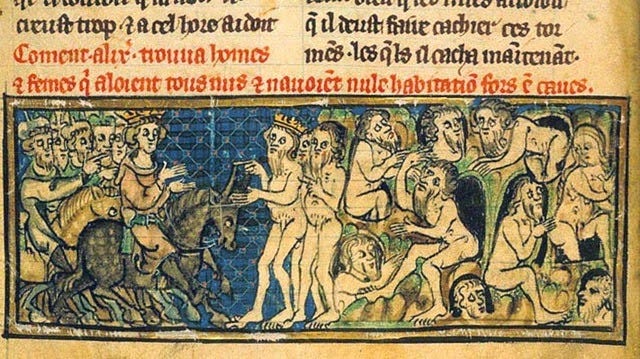

The Outlines is a complete work on Pyrrhonism surviving from antiquity, and readers often smell more than a whiff of similarity between its content and the Buddhist tradition. This is probably because Pyrrho did spend quite some time in India, following the expedition of Alexander the Great, and talked to a group of monks known to the Greeks as gymnosophists (literally, naked wise men), probably representatives of early Buddhism (of which also there is no surviving written record, by the way). It is useless to speculate how much the Greeks influenced the Buddhists and vice versa, since we don’t have historical testimonies to that effect, and at any rate cultural exchanges are always a matter of cross-pollination.

The Outlines is comprised of three “books,” where a book was the text that would fit on a single roll of papyrus. The first book is a general introduction to Pyrrhonism, the second takes up criticism of logic as understood by other schools, and the third one expands that criticism to physics (i.e., natural science) and ethics, thus comprising the three major branches of the standard philosophical curriculum in the ancient world. As Bett writes: “Anyone who claims expert knowledge on any subject is fair game, as far as [Sextus] is concerned.” As it should be, I would add.

How does Pyrrhonism work in practice? Through three successive stages:

I. Produce counterarguments. Consider any view that smells of dogmatism, for instance the Stoic proposition that virtue is the only good. Then work hard to put forth a contrary view, say similar to the Epicurean one that the true good is lack of pain.

II. Suspend judgment. If you’ve done your work well and represented the two (or more) opposing views charitably and effectively, then you’ll begin to feel an inclination toward suspending judgment, because you’ll see that each view has both merits and problems.

III. Serenity ensues. The Pyrrhonist bet is that, once you have managed to distance yourself from specific dogmatic positions, because you’ve seen that there really is no conclusive argument in favor of one or the other, then you’ll be on your way to ataraxia.

To be fair, all three of the above steps can be challenged by someone who is, shall we say, skeptical of Pyrrhonism.

To begin with, it is simply not the case that every position can be associated with a counter-position of about equal argumentative or empirical strength. This works in some cases, perhaps, but very clearly not in others. For instance, contemporary cutting edge theories in fundamental physics—an obvious example of what the Pyrrhonists call non-evident matters, are controversial precisely because, at the moment, there is no clear winner.

But if we shift to an evaluation of, say, evolutionary theory vs so-called “scientific” creationism, not even the most fair and able Pyrrhonist could come up with anything resembling a good argument in favor of the latter. There simply is no equivalency there. This doesn’t mean that we should consider the matter settled in favor of the current version of Darwinism. New discoveries will likely lead scientists in novel directions, and revisions to the theory will be made accordingly. But the notion that we might ever get back to creationism is too far fetched to be taken seriously.

The second step of the Pyrrhonian algorithm is also questionable. Are human beings truly capable of suspending judgment? I don’t know about you, but I find it exceedingly difficult. That’s not because I’m a particularly judgmental person (I don’t think!), but rather because if I devote sufficient time to a particular matter or controversy I will be able to find arguments and/or evidence that will allow me to discriminate, at least tentatively, in favor of one option over another. True agnosticism is a highly unstable state, both psychologically and epistemically.

Finally, does serenity really ensue once we suspend judgment? This may sound plausible, but, ultimately, it is an empirical question, and one could argue that it is just as likely that suspending judgment will cause some people a lot of anxiety, because they’ll be unable to make up their mind about matters they find to be important. More research needs to be done, as they say!

There is another standard criticism of Pyrrhonism to be considered: if we suspend judgment all the time, on what basis do we act in daily life? This was an issue raised in antiquity by the Stoics. But to be fair it hinges on a misunderstanding of the Pyrrhonist position.

Sextus is very clear on the fact that suspension of judgment is recommended for non-evident matters, not for daily operations. In the latter case we simply go with our inclinations (I feel hungry, so I eat), or with the custom of the society in which we find ourselves (when in Rome…).

These Pyrrhonist retorts, however, in turn raise yet more issues. I mentioned above that it isn’t at all clear what exactly (or even approximately) the distinction may be between evident and non-evident matters. And Sextus never seems to spell it out explicitly.

Moreover, to simply follow local customs is a recipe for a stale society that lacks innovation, particularly in terms of ethical matters. I suppose that if a Pyrrhonist finds himself growing up in an environment where genital mutilation of young girls is practiced and accepted he will simply go along, because he would feel too much like a dogmatist if he raises objections on moral grounds. Well, in that case go ahead and count me a dogmatist!

The above considerations explain why my personal preference, when it comes to skepticism, is for the Academic variety practiced by Carneades and Cicero, rather than the one put forth by Pyrrho and Sextus. According to Carneades, we are in the business of assessing the persuasiveness of any given notion, tentatively (but only tentatively!) agreeing with the ones that seem to have the highest probability of being true. That way we retain the skeptic’s distinctive distrust of dogmas and are mindful of keeping an open mind about things, but we can still agree or disagree on specific matters—whether evident or not—in proportion to how convincing the arguments pro and con appear to be when thoroughly examined.

That said, the Pyrrhonists do seem to me to make a good point when they suggest that we are too emotionally invested in things that are far more uncertain than we appear to think. Take political opinions, for instance. We currently live in a highly divided society where political polarization has become a way of life, with nasty consequences on societal discourse and, possibly, the very future of democratic institutions. Yet, many political disagreements hinge on a large number of factors that are difficult to evaluate. What should we do about the war in Ukraine? How should the world tackle climate change? What’s the best way to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict? What about China and Taiwan? If anyone has high confidence in quick and simple answers to these and similar questions that person could use a large dose of Pyrrhonian skepticism.

Indeed, Bett concludes his introduction to Outlines by suggesting that skepticism can be a powerful force against fanaticism and for political tolerance. And we desperately need anything that can help us in that department.

Here are some highlights from the actual text, with accompanying brief explanations:

“The skeptical approach, then, is called investigative, from its activity involving investigation and inquiry.” (1.7)

Here Sextus provides us with a valuable lesson in etymology. “Skeptic” means someone who investigates, who is involved in active and open-ended inquiry. It is highly unfortunate that the commonly accepted modern sense of the term is exactly the opposite, indicative of a close-minded person who doesn’t believe anything.

Incidentally, I write a regular column for a magazine called Skeptical Inquirer, devoted to critical investigations of potentially pseudoscientific notions. I have never had the courage to remind its long-time editor, Ken Frazier, that the name of the publication is redundant: skeptical inquirer literally means inquiring inquirer…

“If one says that a school is an attachment to many doctrines that are consistent with one another and with apparent things, and by ‘doctrine’ one means assent to an unclear matter, we will say that [the Pyrrhonist] does not have a school.” (1.16)

This is an interesting point: is Pyrrhonism a school of thought, that is a philosophy, or should it rather be characterized as a philosophical attitude about claims to knowledge? Despite what Sextus writes in this passage, I think he’s off the mark. Pyrrhonism is a philosophy of life in the sense that it does make statements about what is good (ataraxia) and how to get there (epoché). In this it doesn’t seem to be much different from the Epicureans, who also consider ataraxia to be the ultimate goal, though they think we can get there by avoidance of pain rather than suspension of judgment. I’ll leave it to others to debate whether, therefore, Pyrrhonism is itself a kind of dogmatism, despite loud protestations to the contrary.

“This ‘routine of life’ seems to have four aspects: one is involved with the guidance of nature, one with the necessity of how we’re affected, one with the handing down of laws and customs, and one with the teaching of skills.” (1.23)

Sextus clears up a common misunderstanding of Pyrrhonism, to which I have alluded above. Despite their practice of suspension of judgment about non-evident matters, the Pyrrhonists do deploy criteria for everyday living. Four criteria, to be specific: the guidance of nature (about what we should or should not pursue, like avoiding pain and seeking pleasure); our necessities (e.g., being hungry, or thirsty); laws and customs (of the specific society we happen to live in); and what we are taught by people who are proficient at a certain activity (e.g., when learning a musical instrument, or training for a job). Note that these four categories would all count as concerning evident matters.

“The biggest evidence of the great and endless difference in the thought of human beings is the disagreement in what is said by the dogmatists about (among other things) what we ought to choose and what we ought to avoid.” (2.85)

This is one of the famous “ten modes” by which the Pyrrhonists train themselves to arrive at suspension of judgment. It stems from the common observation that people, including experts, vehemently disagree on all sorts of non-evident matters. What is the world made of, ultimately? The Presocratic Thales of Miletus said it was water; one of his students, Anaximenes, said it was air. For another Presocratic, Heraclitus, it was fire. According to modern physicists it is either quarks and other particles or vibrating strings. Or fields. Who knows. You see the point: why strongly endorse, and becoming emotionally attached, to any of these? Relax and chill out, man…

“The method of induction, I think, is easy to dispose of. Since they want to use it to guarantee the universal from particular cases, they will do this by going over either all the particular cases or just some. But if it’s just some, the induction will not be secure—it’s possible that some of the particular cases left out in the induction go against the universal. But if it’s all, they will have an impossible struggle; there’s an infinite number of particular cases—you can’t put a limit on them. So either way, I think, it turns out that induction is shaky.” (4.204)

This is arguably the first instance in the history of western philosophy where the reasoning mode known as induction—the generalization from a sample of instances to a universal rule—which is fundamental to both everyday and scientific discourses, comes under attack. The sort of issue that Sextus raises in this context will eventually be taken up again by David Hume in the 18th century, and still today represents the obligatory starting point for any discussion on induction.

Incidentally, just before this passage Sextus had also criticized deductive reasoning, common in logic and mathematics. A major point of criticism is that one or more of the premises that go into deductive arguments is usually itself derived from induction. And since the latter is shaky, then this means that deduction too is shaky. Now there goes a lesson in epistemic humility!

[Next in this series: How to be a leader according to Plutarch. Previous installments: I.]

This is one I’ve somehow missed. Will check it out!

Up to a point. In my research career, I chose problems relevant to the non-evident matter of the origin of life, being a partisan supporter of the view that inorganic substrates played (forgive the choice of words) a vital role, and though I was not dogmatic in rejecting alternatives this attachment gave me much motivation and pleasure. These days I regard the matter with Pyrrhonic detachment, but as a result following developments is little bit like watching a football match where you don't care who wins.