You may noticed that we live in a world of extreme consumerism, where economists are finally beginning to take seriously the problem posed by so-called “externalities,” that is the costs and deleterious effects associated with the production of human goods. There is much talk, nowadays, of growing food locally because of the environmental degradation caused by global trade. And we still struggle to recognize and ameliorate the suffering of countless human beings that are being exploited so that we can have our mostly useless stuff delivered at our doorstep, pronto.

And yet, none of this is new. Such problems were certainly understood by an anonymous ancient writer known as Pseudo-Lucian, because he was the actual author of some of the writings historically attributed to Lucian of Samosata (125-after 180 CE).

Lucian himself was a fascinating fellow. He was a Hellenized Syrian and made his living as an itinerant teacher and a satirist. He made fun of pretentious people and public figures, as well as of belief in tall tales and superstitions. He is credited with writing the first science fiction story, A True Story, which features travel to space, aliens, and interplanetary warfare. Lucian inspired writers through the centuries, including Thomas More, François Rabelais, William Shakespeare, and of course Jonathan Swift, particularly his Gulliver’s Travels.

This essay, however, is not about Lucian but Pseudo-Lucian, who presumably lived a little later and who wrote in very much the same style and on similar topics. This wasn’t plagiarism, as we understand it today, but rather a fairly common approach whereby an author would write “in the style” of another one, consciously and with admiration, or even just as an exercise in finessing their own writing.

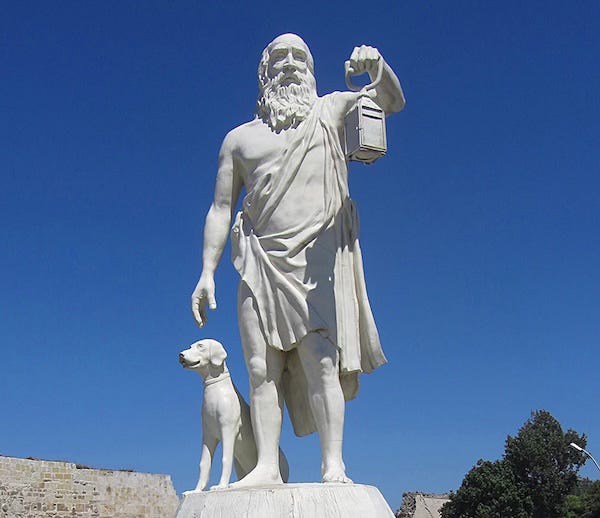

The dialogue by Pseudo-Lucian I am interested in is excerpted from his The Cynic, and features a fictional interview between a critic of the philosophy of Cynicism and a Cynic who defends it. The attacker is named Lykinos, which literally means “wolf-like,” and the defender is named Kynikos, which means “dog-like,” an obvious reference to the Greek root of the word Cynic. You can find the full dialogue translated by Mark Usher in his How to Say No: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Cynicism, about which I have written before here at FiW.

Lykinos, the critic, opens the dialogue in a fairly aggressive manner: “Hey, you there—you’ve got a beard and long hair, but why no shirt? … Why have you chosen a vagrant, antisocial, animal-like lifestyle?”

Kynikos very simply responds that the cloak he is wearing is easily obtained, costs little, and is easy to maintain. He then poses a question of his own to his interlocutor: doesn’t he think that extravagance is connected with vice while virtue is linked to simplicity?

But Lykinos doesn’t want to hear it, instead going on insulting Kynikos, telling him that he is no different than a beggar. The latter then makes a Socratic move, asking whether it wouldn’t be useful at this point in the conversation to closely examine what lack and sufficiency actually are. Lykinos grudgingly agrees.

The philosopher, again in perfectly Socratic fashion, gets the other to agree to two propositions: sufficiency is whatever meets someone’s needs, while lack is what falls shorts of that mark. He then concludes: “Then there’s nothing lacking in my affairs. Nothing in my lifestyle fails to accomplish its end, as far as my needs go.” QED, score 1 for the Cynics.

The dialogue continues with an examination of what else may be lacking in Kynikos as a result of his choice of life. His body seems to be in good shape, doesn’t it? Yes, agrees the other. Then the simple nutrition he gets must be sufficient. Indeed, it appears so. Kynikos at this point poses the question: “So, tell me, then, why on earth, since all these things are so, do you censure me and belittle my lifestyle and say it’s miserable?”

The critic has an answer, but it becomes increasingly clear that it simply reflects his own prejudices. He says, among other things, that Kynikos drinks and eats like an animal, his bed is no better than a dog’s, and his cloak of the same quality as that of someone who is destitute. Lykinos concludes that to live like that on purpose is sheer madness, thus echoing Plato’s famous remark about one of the early Cynics, Diogenes of Sinope, when he referred to him as “Socrates gone mad.”

With near infinite patience, and a bit of sarcasm, Kynikos explains that God acts toward us as a good host would: he places in front of us a variety of dishes, depending on what we actually need. Lykinos, by contrast, acts with greed and lack of restraint, grabbing everything that comes his way.

“You don’t think your own land and sea are enough in themselves but import your pleasures from the corners of the globe and always prefer what is foreign to what is produced locally. … The many costly goods you think conducive to your happiness, over which you exult, only come to be yours through misery and suffering.”

This sounds stunningly modern, and is a sharp reminder of why it pays off so handsomely to read the classics: those people were like us, plagued by the same problems, and they developed timeless insights that are still very much applicable today. It doesn’t matter that we go after different kinds of luxuries than they valued. The general principles remain the same, mutatis mutandis (with respective differences taken into consideration), as the Medievals used to say.

Kynikos goes on, rhetorically asking Lykinos how much it costs to get him what he wants in terms of human labor and suffering, blood, danger, and destruction.

“And yet embroidered robes can keep you no warmer, gilt houses cannot provide more shelter, cups of gold and silver don’t help the taste of drink, nor do beds carved from ivory offer you a sounder sleep.” Think about that the next time you buy from China using Amazon, instead of going to a local business near you.

Of course, Kynikos wouldn’t be a good Cynic if he didn’t address another common human urge: “Need I also mention all the trouble people cause and suffer in pursuit of sex? Yet it’s easy to service that urge—unless one opts for extravagance.”

The broader point, the philosopher continues addressing his critic, is that you chide me for living a simple life, while it is your own unsustainable lifestyle that causes trouble and suffering, not mine.

“May I have the whole Earth for a bed that is sufficient in itself. May I consider the universe my home. May I choose for food what is easiest to obtain. Gold and silver, may I, and my friends, need none. All human woes spring from desire for it—civic conflicts, wars, conspiracies, and slaughter.”

By this point Kynikos is on a roll:

“You refuse to walk but are carried around like cargo, some of you by human beings, others by oxen. But me, my feet take me wherever I need to go, and I am capable of enduring heat and cold. … You, for all your happiness, are satisfied with nothing that transpires, find fault with everything, are unwilling to accept what you have and yearn for what you don’t, praying for summer in winter and winter in summer, for cold weather in hot and for hot weather in cold.”

Does this not sound like an indictment of 21st century consumerism? Could you not see Kynikos nodding in agreement with a modern who is concerned with the environment? The problem, says the Cynic, is that most people don’t use their brain. They do things by habit and appetite, carried away by the torrent of their basic drives, without stopping to think for a moment about the consequences of their actions, both for themselves and for the rest of the planet.

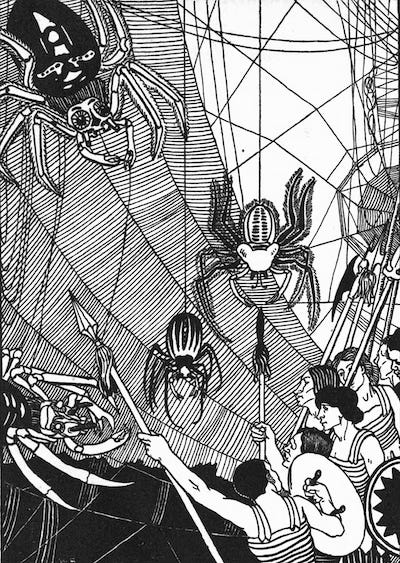

This torrent is sweeping us away toward a cliff and into a ravine, says Kynikos, and we have no idea of what is about to happen to us, until it is too late. Again, climate change, anyone?

The Cynic then concludes:

“This old cloak, which you ridicule, and my hair and my whole getup gives me considerable power in that they allow me to live in peace and quiet, doing whatever I want with whomever I want. … But at the doors of the so-called happy people I pay no court. Rather I consider their golden crowns and purple robes nonsense and laugh at people who wear them.”

Shall we meditate on this a bit?

Although there a overlapping stories in Lucian's True History and the Tales of Baron von Munchausen, I haven't ever seen any direct attributions. Your digression on Lucian was very pleasing, since he has long been a favorite writer of mine.

I agree that luxury is absolutely unnecessary to a good life and that it probably breeds vices like envy