We tend to think of Marcus Aurelius as a philosopher-king, and in a sense he was, though the ancient Romans were allergic to the word “king” and preferred Imperator, which technically just meant supreme commander of the troops, the equivalent of a modern American President being hailed as “commander-in-chief.”

Emperors ever since the first one, Octavian Augustus, the adopted son of Julius Caesar, also liked to present themselves as “princeps,” which literally meant, somewhat oxymoronically, “first among equals.” As an added bonus, both “imperator” and “princeps” were terms that arched back to the time of the Roman Republic, which many still considered to have embodied the ideal form for a State.

Anyway, back to the philosopher part of “philosopher-king.” Marcus had not just studied philosophy, but also rhetoric, history, and the arts. Accordingly, we find this stunning comment near the beginning of the eleventh notebook of the Meditations:

“After Tragedy the old Comedy was put on the stage, exercising an educative freedom of speech, and by its very directness of utterance giving us no unserviceable warning against unbridled arrogance. In somewhat similar vein Diogenes [the Cynic] also took up this role. After this, consider for what purpose the Middle Comedy was introduced, and subsequently the New, which little by little degenerated into ingenious mimicry.” (XI.6)

There is a lot going on here. Marcus is distinguishing four kinds of popular entertainment that succeeded each other in ancient Greece, and eventually in Rome. He begins with tragedy. Think of names such as those of Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, among the greatest playwright of all time. They all lived during the 5th century BCE, during what is considered Athens’ golden age.

The writings of the classical tragedians were meant not just to entertain, but to impart lessons in morals and history. Consider Aeschylus’s The Persians, about the second invasion of Greece by the Achaemenid Empire of Cyrus the Great. Or Sophocles’s Antigone, about a woman defying the decree of a king in the name of universal moral law. Or Euripides’s The Trojan Women, an overtly critical treatment of the horrors of war, written in the middle of the Peloponnesian conflict that pitted Sparta against Athens and eventually led to the destruction of the latter.

After such classic works, Marcus recalls to himself, we saw the rise of Old Comedy, most deservedly represented by Aristophanes, who engaged in satirical commentary on the society of his time, for instance with his racy anti-war farce, Lysistrata. That sort of thing, says Marcus, still had value because it embodied freedom of speech and allowed criticism of the powers that be, whose chief representatives were singled out by name.

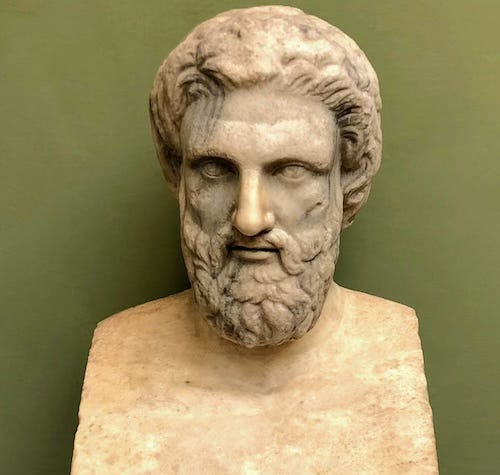

It is notable that Marcus associates the name of the Cynic philosopher Diogenes of Sinope to Old Comedy. The Cynics were iconoclasts bent on ridiculing the prevalent social mores, and one of them, Menippus of Gadara, actually originated a new form of satire that took his name. The only intact surviving example of it was written by the Stoic philosopher Seneca the Younger, entitled The Pumpkinification of the Divine Claudius, and is a parody of the bizarre Roman custom of making dead emperors into gods.

But after the valuable Old Comedy came Middle and then New Comedy, which clearly Marcus does not think very highly of. Why not?

Middle Comedy no longer featured actual, recognizable individuals as targets for satire, say a prominent politician. Instead, it made fun of generalized caricatures, or stereotypes as we would call them today. Middle Comedy stayed away from political issues, and its stock characters included courtesans, revelers, philosophers, and conceited cooks. As modern comedians might put it, it was about punching down, not up.

New Comedy became popular after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE, and is best exemplified by Menander of Athens. It was comparable to our sit-coms and comedies of manners, that is, again, with little or no political content or social commentary, written just for laughs.

Marcus’s point here is very interesting, particularly because it comes from someone who personified the powers that be! He is saying that a healthy society needs the likes of Sophocles and Aristophanes, and that if it instead gets a Menander, as entertaining as he may be, something important in public discourse is lost.

What does that say about our own society, which is overwhelmed by sit-coms but where there are very few Sophocles to be found? And by contrast, what does it say about us that the best political and social commentary around is offered (in my opinion) by late night comedians like Stephen Colbert and Jon Stewart?

I just commented on Tim Snyder’s recent post on Substack. Starts with Greek tragedies and Icelandic sagas. For a historian of European times this reminder that ancient plays are important to fathom.

I was expecting also to read about new comedy...