Philosophy as a Way of Life—I—How to run a philosophical school

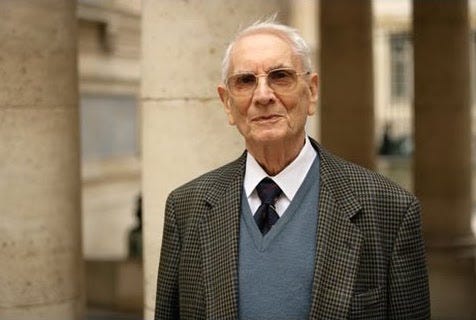

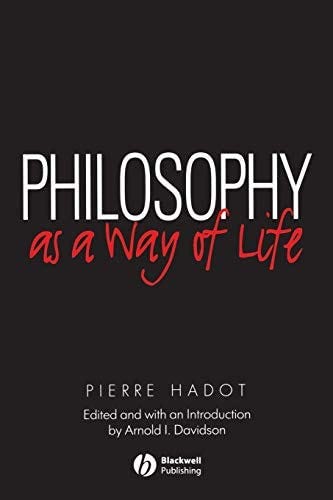

Pierre Hadot’s ideas on ancient practical philosophy are foundational to the modern conception of the art of living

Whether we realize it or not, we all have a philosophy of life. Often it consists in whatever religious creed and practices one has been raised with. At other times it is the result of a conscious choice. Even those who don’t think about philosophy or religion still have a certain understanding of the world and how to act within it—which means that they have a (implied) life philosophy.

If this is the case, we may as well be conscious of what kind of philosophy we practice and why. And at least occasionally we may want to question whether such philosophy is really what we want. If the answer is yes, good. If it’s no, then perhaps the time has come to consider possible alternatives.

A good number of the possible alternatives on the table belong to a cluster of Greco-Roman philosophies of life developed during the millennium between the 5th century BCE and the fifth century CE, give or take. It’s hard to imagine a better guide to those practical philosophies than French scholar Pierre Hadot, for instance in his book Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault. The series of essays of which this is the first installment is devoted to a summary and discussion of Hadot’s ideas as put forth in that book, in the hope of being helpful to people who are either in the process of choosing a new philosophy for themselves or are practicing one already and want to get better at it.

Hadot reasonably suggests that ancient philosophical schools thrived—and have therefore come to be known to us—when their founders established them as institutions: Plato’s Academy, Aristotle’s Lyceum, Epicurus’ Garden, and Zeno’s Stoa. (By contrast, for instance, we know little of the Cyrenaics.) In addition to these we have what Hadot calls two spiritual traditions: Skepticism (in two forms: Pyrrhonism and Academic Skepticism) and Cynicism.

From around the third century Platonism began a process of synthesis of Aristotelianism and Stoicism, while the remaining traditions gradually faded away. The resulting Neoplatonism will come to dominate the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, setting the stage for the modern era. In other words, Greco-Roman philosophy did not die with the end of the classical period, but shaped western thought (and beyond) for another millennium and a half after that, and is still very much with us today.

Hadot says that to philosophize meant to enact a deep rapture with bios, that is, the normal life conducted by most people. Philosophers, in other words, rejected commonly accepted priorities in favor of rather unusual ones, like virtue, or mental tranquillity, or the suspension of judgment. As a result, philosophers were seen as strange and potentially dangerous, and made fun of by the public and by comics like Aristophanes, who in his The Clouds (423 BCE) made fun of a certain Socrates, often referred to as atopos, meaning unclassifiable. This strangeness and unclassifiability may have contributed to Socrates’ trial and execution in 399 BCE. (Certainly Plato held Aristophanes in part responsible for that unfortunate turn of events.)

Part of what made practical philosophy a bit “strange,” from the point of view of the person in the street, so to speak, was that the various schools conjured their own version of the sage, a hypothetical individual whose ideal life was, again, a stark departure from the life of common people. Consider, for instance, the Stoic sage, who never gets angry or upset, and always tackles problems by way of rational analysis. Moreover, the Stoic sage has very different priorities from the rest of humanity. For her things like health, wealth, reputation, and career are “indifferents,” meaning that they have value but do not affect the most important thing of them all: our character.

It’s not clear whether the Stoics thought that sages actually exist. Seneca tells us (in his 42nd Letter to Lucilius) that they are as rare as the mythological phoenix, which rises from its ashes once every 500 years. Nevertheless, the figure of the sage is crucial because it plays a role analogous to that of Jesus in Christianity, or Buddha in Buddhism: it represents an ideal toward which we ought to be striving, regardless of how challenging it may be.

In order to help us practitioners each school devised “spiritual” exercises aimed at ethical self-improvement. I will devote a separate post to exploring this notion in some detail, but the two major kinds of exercises are concerned with self-control and meditation.

Self-control is about paying attention to oneself, learning to better handle anger, speech, love of wealth, and all the other “externals.” The goal is to develop a stable and good character. Socrates, in Xenophon’s Memorabilia (IV.5) argues that self-control is the key to all the other virtues.

Meditation, by contrast, is about exercising reason. It’s very different from its Buddhist counterpart and it consists in reflecting on and assimilating the rules of conduct according to each school. The goal, ultimately, is to change one’s entire view of life and what it is about.

The philosophical practitioner makes progress by learning to keep a series of basic precepts always “at hand” for use in whatever situation presents itself. The entire Enchidirion by Epictetus is a collection of such handy recommendations.

This practice and progress, Hadot reminds us, emphasizes two practical objectives: living in the present, the only time where our agency is effective; and preparing oneself for death, so that one can live and enjoy life in full consciousness, mindful that such life is finite and that we don’t really know when it will end.

In order to train in one of the Greco-Roman schools theory was obviously necessary, but certainly not as an end in itself (as it is, unfortunately, the case in much contemporary academic philosophy). Theory is valuable only if it aids practice, as Epictetus forcefully reminds his students in his inimitably sarcastic style:

“‘I want to know what Chrysippus has to say in his treatise about the Liar.’ Why don’t you go off and hang yourself, you wretch, if that is really what you want? And what good will it do you to know it? You’ll read the whole book from one end to the other while grieving all the while, and you’ll be trembling when you expound it to others. And the rest of you behave like that too. ‘Would you like me to read something out, brother, and you can do so for me in turn?’—‘My friend, you write astoundingly well.’—‘And so do you, splendidly, quite in the style of Xenophon.’ —‘And you in the style of Plato.’—‘And you in the style of Antisthenes.’ And then, when you’ve recounted your dreams to one another, you fall back into the same old faults; you have the same desires as before, the same aversions, the same motives, plans, and intentions, you ask for the same things in your prayers, and have the same [misguided] preoccupations.” (Discourses, II.17.34-36)

Ouch. A friend of mine once suggested that Epictetus must have sounded like Rocky Balboa’s trainer, dispensing tough love to his students in Nicopolis. Just like an athlete picks a trainer and sticks with the choice, the first step to adopt philosophy as a way of life in ancient Greece and Rome was to choose a school (and a teacher) and try to stick to its principles in one’s everyday life. Stoicism and Epictetus; or Peripateticism and Aristotle. But not both.

Nowadays, however, there aren’t many opportunities to walk into an equivalent of Epicurus’s Garden, or to stop by the local Stoa and listen to Zeno. Instead, we read the ancient texts and try our best to interpret them in a way that makes sense to modern audiences. One reason this may be challenging, at least initially, is because those texts were written in a manner that was still very much influenced by the oral traditions that preceded them. Don’t forget that several philosophers, including Socrates and Epictetus, didn’t write anything at all. As Hadot puts it:

“Quite often the work proceeds by the associations of ideas, without systematic rigor. The work retains the starts and stops, the hesitations, and the repetitions of spoken discourse.” (p. 62)

When it came to teaching philosophy, the written word was chiefly seen as an aid to memory. The real work was done during conversations between teachers and students, as we can glimpse from the Socratic dialogues by both Plato and Xenophon, as well as by the Discourses of Epictetus, a collection of interactions of the master with his students put together by Arrian of Nicomedia. Indeed, often the texts were meant to accompany the teacher’s lessons, as in pretty much everything that survived by Aristotle. That’s why we can’t read these works as if they were aimed at a general public, modern or not. And that is why the work of modern translators and commentators is so important in order to get the rest of us to appreciate Greco-Roman thought.

If you frequented one of the ancient schools, a major exercise for you and your fellow students would be to discuss a given theme either dialectically (i.e., in the form of questions and answers) or rhetorically (i.e., as a continuous exposition). The theme was often posed as a question to get the student started: Is death an evil? Does the wise person ever get angry? You can read this way Cicero, Plutarch, Seneca, and Plotinus, that is, the vast majority of the surviving ancient sources.

Another exercise for a student may be to read and engage in the exegesis of a given authoritative text, pretty much what I’m doing here with Hadot himself. After all, in order to explain it to others, you have to first understand it well yourself! This is why we have a large number of commentaries on Plato, Aristotle, and so forth surviving from antiquity.

Whatever the form, writings from the ancient schools always have the aim not just to expound on a particular topic, but to help readers along their spiritual journey, as Hadot explicitly reminds us:

“One must always approach a philosophical work of antiquity with this idea of spiritual progress in mind.” (p. 64)

Ultimately, according to the traditions we are discussing, we only need ourselves (not externals) to find happiness, here and now, no need to worry about either the past or the future—both of which are outside of our control anyway. The corollary is that if you can’t be happy now, you’ll never be happy. Happiness, in a very important sense, is an inside job. Accordingly, Hadot concludes his analysis of how the ancient schools were run with the following observation:

“The concern with individual destiny and spiritual progress, the intransigent assertion of moral requirements, the call for meditation, the invitation to seek this inner peace that all the schools, even those of the skeptics, propose as the aim of philosophy, the feeling for the seriousness and grandeur of existence, this seems to me to be what has never been surpassed in ancient philosophy and what always remains alive.” (p. 69)

And those are precisely the reasons we still very much engage the Greco-Romans and keep learning from them.

[Next in this series: Spiritual exercises.]

_____

Post scriptum: I have previously published a nine-part commentary of another of Hadot’s books, The Inner Citadel, dedicated to the philosophy of Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius. Here are the individual entries:

2, A first glimpse of the Meditations

3, The Meditations as spiritual exercises

4, The philosopher-slave and the emperor-philosopher

5, The beautifully coherent Stoicism of Epictetus

7, The discipline of desire, or amor fati

8, The discipline of action, in the service of humanity

Great article! And right from the start: "Whether we realize it or not, we all have a philosophy of life." - I couldn't agree with this more. So worthwhile to consider what one's philosophy is... and if it good as well as consistent.

Well said, looking forward to reading the other parts!