Profiles in skepticism: Arcesilaus, founder of the Skeptic Academy

Plato’s school went skeptical. Why? It was a return to Socrates, of course.

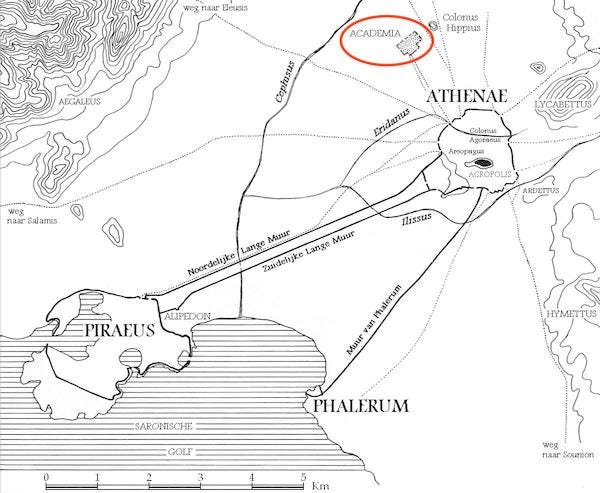

Plato’s Academy, established in 387 BCE in Athens, ended up being the longest running philosophical school of the western tradition, eventually shut down by the Christian emperor Justinian in 525 CE, nine centuries later. During its long and fascinating history it went through a number of philosophical phases, one of which began in 264 BCE, when Arcesilaus of Pitane became the sixth head (scholarch) of the Academy and oriented it toward skepticism.

Arcesilaus claimed to be influenced by Socrates (of course), Plato (obviously), and some of the Presocratics. He was also very clearly influenced by Pyrrho. He explicitly claimed not to be saying anything new, but rather to re-introduce and popularize the ideas of his predecessors. Nevertheless, he is historically important because he changed the whole nature of the school founded by Plato, as very nicely explained in an essay by Anna Maria Ioppolo, part of a collection entitled Skepticism: From Antiquity to the Present edited by Diego Machuca and Baron Reed.

Despite his profession to lack originality, Arcesilaus was attempting to produce a new, eclectic form of Platonism which combined elements of various other philosophies that he thought valuable. He was harshly criticized for this. Aristo of Chios, an heterodox Stoic, made fun of Arcesilaus for having produced a horrible philosophical chimaera, featuring, as he put it, “Plato in front, Pyrrho behind, Diodorus in the middle,” Diodorus Cronus being a dialectician associated with the Megarian school of logic.

The joke, however, was on Aristo. The school to which he professed to belong, Stoicism, itself got started as a chimaera of made out of heterogenous ideas. His own teacher, Zeno of Citium, had assembled Stoic philosophy from elements of Cynicism, Platonism, the teachings of the Megarians, and a sprinkle of Presocratic thought, especially from Heraclitus.

This raises the general issue of whether it is a good idea to look for eclectic, or syncretic philosophies. The answer is: it depends. On the one hand, pretty much no philosophy (or religion, for that matter) arises out of nothing. It is always a recombination of previous ideas, mixed with some innovation. Sometimes it is a response to old ideas, as in Buddhism’s reaction to the Brahminic tradition.

On the other hand, you don’t want to be so eclectic that the result is an incoherent mess. Apparently, Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, came close to such a mess, which is why it was eventually up to the third scholarch of the School, the logician Chrysippus of Soli, to do some house cleaning and create Stoicism as we understand it today:

“Had there been no Chrysippus, there would have been no Stoa.” (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, VII.183)

Still, we can reasonably ask the question: why a skeptical turn for the Academy? Well, Socrates can be thought of as a skeptic of sorts, when he insists in denying that he knows anything, claiming that his main goal is inquiry (the literal meaning of the word “skeptic” is “inquirer”). So this attitude, which we also find in Presocratics like Anaxagoras, Democritus, Empedocles, and Heraclitus, can indeed be said to be broadly Socratic. Arcesilaus, therefore, had some justification for his decision to go back to the basics, so to speak. However, he went one step further than Socrates, saying that he couldn’t even claim not to know anything, because that in itself is a claim to knowledge.

In his Academica, Cicero presents us with a dialogue between Arcesilaus and his contemporary, the Stoic Zeno of Citium. The interaction between the two marked the beginning of a multi-generational debate featuring the two schools, which reached its peak with the confrontation between Carneades and Chrysippus, the subject of the next essay in this series.

The debate was about epistemology, the branch of philosophy that is concerned with truth claims and the nature of evidence. The Stoics claimed that definite knowledge is possible, at least for the sage, the ideal human agent. To understand why we need to grasp the concept of an “impression,” which was common to various Hellenistic schools.

Let’s say that I look across the street and I see my brother walking toward the park. This is an example of sensorial impression. It is made of two components, in Stoic psychology: (i) I receive information about the external world through my senses; and (ii) I more or less automatically interpret the meaning of that information, in this case arriving at the judgment that it is my brother who is walking toward the park.

But of course, being human, I could be wrong. Perhaps it is someone who looks like my brother. Indeed, now that I think of it, I know that my brother is currently in Rome, so he couldn’t be crossing the street here in Brooklyn. I revise my judgment accordingly, denying “assent,” as the Stoics say, to the initial impression.

Then again, even my revised assent could be wrong. My brother might have lied to me about being in Rome, or perhaps my memory is faulty and I forgot he was coming to visit. And so forth.

The Stoics acknowledged that most human beings cannot be certain of the truth of any given impression, on this point agreeing with the skeptics. However, the Stoics thought that there is a special type of impression, which they called “cognitive” (or, to use the Greek term, kataleptic), which bears unmistakable marks of truth, so much so that we simply cannot deny assent to it.

We all experience kataleptic impressions, but only the sage is capable of confidently tell them apart from non-cognitive (i.e., non-truth bearing) ones. For instance, should I poke my head outside of my office right now I would be struck by the kataleptic impression that it is clearly day out there. Nothing and nobody could possibly convince me that it is, instead, the middle of the night. The problem with most of us is that often we think that a given impression is kataleptic while it isn’t, and therefore we assent to all sorts of impressions that turn out not to be true. The sage, because of her perfect ability to reason, never makes this mistake.

Enter the Academic Skeptics. Arcesilaus denied the existence of cognitive impressions. There is no external sure mark of truth in the world. Assent is a human psychological process, and as such it is subject to the known limitations of human reasoning, the reliability of our senses, and so forth. We can be more or less confident of the veracity of a given impression, but not even the sage can self-assuredly and unequivocally assert it.

As John Sellars says in The Art of Living, which in part summarizes this very debate, eventually Academic Skeptics and Stoics came to a compromise position in which each school conceded some of the points of the rival. The Skeptics agreed that one cannot suspend judgment all the time, and that a criterion based on the relative likelihood of any given opinion must be deployed in order to be able to act in life. On their part, the Stoics agreed that even the sage may end up suspending judgment a lot of the time, because too often she will not have sufficient elements on which to judge an impression to truly be kataleptic.

Back to Arcesilaus. His brand of skepticism was not yet as sophisticated as the one that we will soon explore in Carneades and Cicero, and indeed, he was often accused of (or praised for, depending on who was talking) being essentially a Pyrrhonist. Ioppolo cites the late Pyrrhonian commentator Sextus Empiricus as saying:

“[Arcesilaus] seems to me to have very much in common with the Pyrrhonian discourses, so that his school is practically the same as ours.” (Outlines of Pyrrhonism, I.232)

But if Arcesilaus’ skepticism is essentially Pyrrhonism then this raises the question of the basis for action when it comes to what the Pyrrhonists called “non-evident matters,” e.g., questions surrounding ethics, the chief good in life, and so forth.

The Pyrrhonists did not have a particularly good response to that question, which is why they simply suspended judgment. (They did follow local customs for more mundane, “evident” matters.)

But in fact Arcesilaus began to orient the Academic Skeptics in the right direction—and away from Pyrrhonism—by suggesting that action should be based on what appears to be “reasonable,” a concept that Carneades and Cicero will make more precise and operative and which will bring Academic Skepticism to its philosophical peak, as well as provide the rest of us with a very useful framework for making our own decisions.

[Next in this series: Carneades and the peak of the Skeptic Academy. Previous installments: The Cyrenaics; Pyrrho.]

I never read your stuff, Massimo Pigliucci, without having the huge gaps in my education brought into sharp focus--yet you do this without patronizing or shaming me in any way. The way you weave in people and schools of thought that I know a bit about with those I really don't is masterful--thanks.

Eclectic in its common American usage encompasses everything from a grab-bag of incompatible things without reconciliation (people who claim to be Christians but believe in reincarnation) to a synthesis of two overlapping philosophies like you describe. I agree that we must be open to adopt better ideas when encountered and not be fundamentalists who encumber themselves with a rigid view: a past authority being the only guide to truth. After all, that’s what these past authors have done themselves; even when they don’t adopt a different view, they develop their own ideas because of dialogue with others. Thanks for a thoughtful essay and I look forward to starting my day again with your next essay