How do we study and practice philosophy as a way of life? Consider the following extended quote:

“They say that philosophical doctrine has three parts: the physical, the ethical, and the logical. Zeno of Citium was the first to divide it this way in his work On Reason. … These parts Apollodorus calls ‘topics.’ … [He and others] compare philosophy … to an animal, likening logic to the bones and sinews, ethics to the fleshier parts, and physics to the soul. Or again, they liken it to an egg: the outer parts are logic, the next parts are ethics, and the inmost parts are physics; or to a fertile field, of which logic is the surrounding fence, ethics the fruit, and physics the land or the trees. Or to a city that is well fortified and governed according to reason.” (Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, VII.39-40)

There is a lot going on there, and much of it very useful. So let’s unpack it carefully. The first thing to note is that Diogenes Laertius attributes the famous tripartition of philosophy into physical, ethical, and logical to Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism. This may or may not be the case, as Diogenes isn’t always reliable with the historical details. But it is true that many schools, not just Stoicism, adopted this approach to the teaching of philosophy.

Second, let’s be clear on what the three key terms actually mean. “Physics” is physis, which means Nature. So the physical topic really translates to a broad combination of what we today would call natural science and metaphysics, i.e., anything aimed at understanding nature.

“Ethics” does not mean just the study of right and wrong actions, as it is largely construed to be today, but is rather rooted in the Greek word ethos which means character. So it is concerned with who we are, what we do, and why we do it. Or, if you will, with how to live a good human life.

“Logic” also meant something far broader than formal logic, though it did include that as well. Basically, the term applied to anything that has to do with understanding and improving human reasoning, which included rhetoric, dialectics, psychology, and cognitive science.

Accordingly, for the remainder of this essay I will use the terms science (instead of physics), ethics, and logic as approximations of the originals given the above caveats.

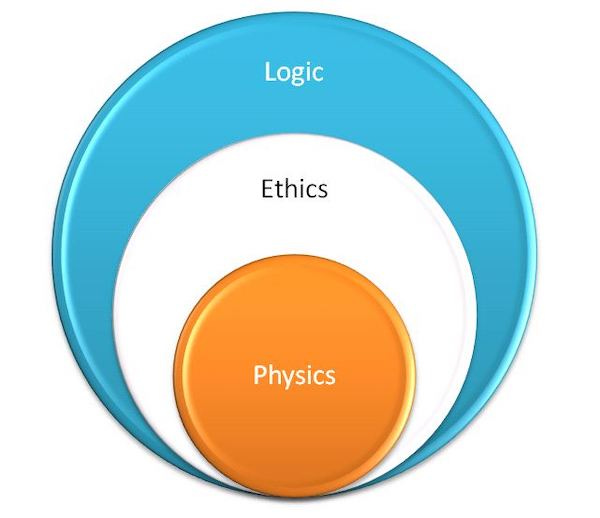

Let us now move to the metaphors themselves. They are varied, and one or another may make more of an impression on you. But they are all about the interrelation of the three topics of study. If you think of them in terms of an animal, then logic is the bones and sinews, ethics the flesh, and science the soul. If you visualize an egg, then logic is the shell, ethics is the albumen (the white stuff), and science is the yolk (the red stuff). Is your preferred metaphor a city? Then think in terms of a well defended place governed by reason (Diogenes Laertius does not give us more details here).

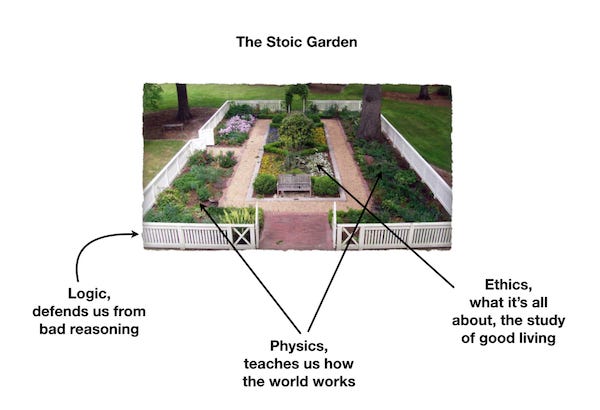

My favorite metaphor is that of a garden: logic is the fence, defending us from the weeds and animals representing bad reasoning. Science is the fertile soil. And ethics is what we really want out of the garden: delicious fruits.

You may have noticed that the various metaphors are not equivalent in terms of the respective positioning of the three topics. For instance, science is the most crucial element in both the egg and the animal, while ethics is what we ultimately want from a garden. Logic, by contrast, tends to take on the role of protector (the egg’s shell, the garden’s fence) or connector (the bones and sinews of the animal).

This variety is not by chance. The ancient Stoics disagreed among themselves on the best sequence of the three topics in the curriculum. Diogenes Laertius continues:

“No part is separate from another, as some of the Stoics say; instead, the parts are blended together. And they used to teach them in combination. Others present logic first, physics second, and ethics third. Among these are Zeno in his work On Reason, as well as Chrysippus, Archedemus, and Eudromus. For Diogenes of Ptolmais begins with ethics, Apollodorus puts ethics second, and Panaetius and Posidonius begin with physics, as Phanias, a student of Posidonius, says in the first book of his work Lectures of Posidonius.” (Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, VII.40-41)

These are the sequences that Diogenes Laertius explicitly mentions:

Logic > Science > Ethics (Zeno, Chrysippus, Archedemus, and Eudromus)

Ethics > Logic? > Science? (Diogenes of Ptolmais)

Logic? > Ethics> Science? (Apollodorus)

Science > Logic? > Ethics? (Panaetius, Posidonius)

Although I doubt this matters very much, if I were in charge of my own school of practical philosophy (hey, there’s an idea! Anyone knows a sponsor who might be interested?) I would follow Zeno and Chrysippus and the garden metaphor. It makes most sense to me to teach logic first, since without that we are hardly in a position to reason correctly about either science or ethics. Next would have to be science, because if we do not understand the world we live in then we cannot make good decisions about how to live in it. So ethics would indeed be the fruits of the whole endeavor.

Epictetus, who in both the Discourses and the Enchiridion talks mostly about ethics, did think logic was basic. Here is a telling exchange with one of his students:

“When one of those who were present said, persuade me that logic is necessary, he replied, Do you wish me to prove this to you? The answer was — Yes. — Then I must use a demonstrative form of speech. — This was granted. — How then will you know if I am cheating you by my argument? The man was silent. Do you see, said Epictetus, that you yourself are admitting that logic is necessary, if without it you cannot know so much as this, whether logic is necessary or not necessary?” (Discourses, II.25)

This conversation, incidentally, applies to any instance in which someone doubts the power of reason, or dwells on its limits and what is “beyond” it. Just remind them that they are making an argument, that is, they are trying to convince you to embrace unreason by using reason. That ought to leave them twisted into a logical pretzel for a while!

Some Stoics, both ancient and modern, wish to drop logic and science and focus on the only thing that (they think) matters: ethics. In antiquity, one such Stoic was Ariston the Bald, a contemporary of Zeno who ailed from Chios:

“He dispensed with the topics of physics and logic, saying that the one is beyond our grasp, that the other does not concern us, and that the only one that does concern us is ethics.” (Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, VII.161)

A modern example is Chuck Chakrapani, who advocates what he calls “Stoic minimalism.” You can find his arguments here, and my response here.

What Ariston and Chuck are doing, essentially, is to reduce Stoicism to Cynicism. It is the Cynics who didn’t think one should bother studying logic and science and should instead focus on ethics. But the problem with that attitude is that it amounts to say that engineers shouldn’t bother with a building’s foundation, which is dirty and dark, and focus instead on what’s above ground. As if we could make buildings without foundations.

What really happens is that Ariston and Chuck actually take on board a lot of logic and science without examining it. They take it for granted that they know how to reason correctly and that they understand the world well enough. Maybe they do, maybe they don’t. The rest of us are better served not skipping the foundations of the curriculum.

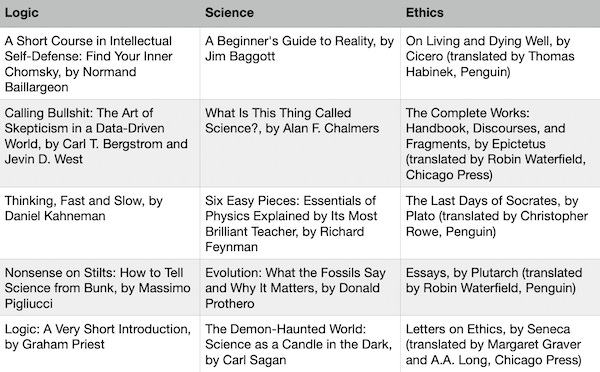

Shall we try to put all of the above into practice today, in the 21st century? Below are some recommendations for a self-taught curriculum that follows the broad outlines of the one adopted by the Stoics and other ancient Greco-Roman schools. The idea is to alternate between columns. Feel free to follow your interests and read the entries within each column in a different order from the straightforwardly alphabetic by author listed here. (Apologies for mentioning one of my own works, but I do think it’s relevant…) Since there are 15 books listed, the full curriculum should take between 30 and 45 weeks to get through, though the actual pace will depend on your other commitments. Please add your recommendations in the discussion section below, for other people’s benefit. Let us strive together to become excellent human beings!

oh, ti voglio bene Massimo. thank you!

Good list! I have read six of these, and some of the others I have read in other translations.