The problem of the perverse

If virtue is natural, how come that most people behave unvirtuously?

One of the most powerful ideas of Stoic philosophy is that we are naturally “virtuous,” by which the Stoics meant that Nature endows us with the ability to reason and an innate tendency to act prosocially. And virtue—according to Seneca—is nothing but “right” reason, meaning reason applied to the betterment of social living (Letter 66.32).

If this is so, then we are faced with what is sometimes referred to as the problem of the perverse: on the one hand, Nature gave us virtue; on the other hand, most of us behave unvirtuously (i.e., either irrationally or antisocially) at least some of the times, if not most of them. What gives?

Before we seek an answer to the problem, let’s make sure the premise is right: are we really naturally virtuous in the way the Stoics assumed? I think so, though not because of the reasons they adduced.

The Stoics believed that the cosmos is a living organism endowed with the Logos, i.e., the ability to think rationally. It followed that there is a providential aspect to the universe. Not in the Christian fashion of a god who loves us and cares for us, but in a more impersonal fashion: we are components of the cosmic being, and our function is to make sure the whole works well and thrives. Apparently, this requires that we share in the Logos, and that we act reasonably and prosocially toward each other.

Think of it this way: you are a cell in a body, and you need to do your part so that the body functions and lives. Part of this task includes cooperating with other cells around you. If you don’t, and start acting unreasonably, you become a cancer.

The above scenario, while ingenious and even comforting, is wrong. The cosmos, according to modern physics and biology, is not a living organism, nor is it endowed with reason [1].

So what are we left with? One of my goals concerning modern Stoicism is to bring its natural philosophy and metaphysics in line with modern science and philosophy. It turns out that both contemporary philosophy and comparative biology do agree with the Stoics that we are naturally “good,” to put it as philosopher Philippa Foot did. Our evolutionary weapons, according to primatologist Frans de Waal et al., are, indeed, our natural tendency to cooperate and our ability to solve problems by reasoning about it.

Given the above, I’m going to take it as the starting point of this article that the problem of the perverse is real. So how do we solve it?

The way Chrysippus and then Cicero did. Let me explain. According to Margaret Graver, in an essay she published in a book edited by Walter Nicgorski entitled Cicero’s Practical Philosophy (chapter 5), Cicero agrees with the Stoics that Nature has given us the means to a good life, which immediately raises the question of why, then, we so often stray from the path laid out for us by Nature.

The problem goes further back than Cicero. In the sixth book of the Republic, Plato has Socrates say that, although we are endowed at birth with various virtues, we are almost always corrupt and made vicious. How is this possible? A partial response we find in both Socrates and the Stoics is that it is society that corrupts us, beginning, often, with our own parents.

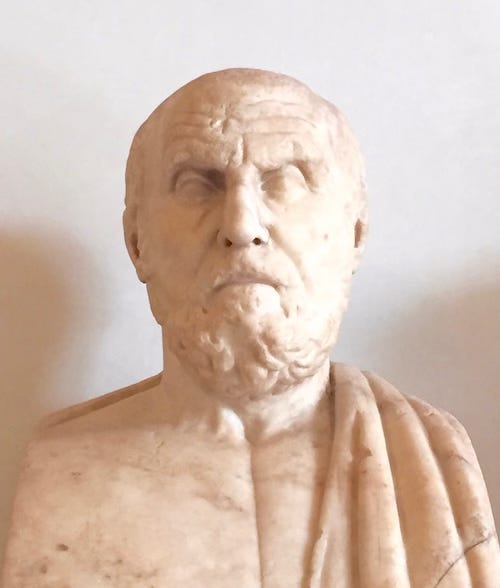

Cicero, however, realizes that that can’t be the whole story, because it doesn’t answer the obvious question of how come that our caretakers and the rest of society are, in turn, corrupt. His own response consists of a two-part account inspired by one of the early Stoics, the logician Chrysippus of Soli, the third Scholarch of the Stoa.

Cicero articulates his account in two of his works: On the Laws (book 1) and Tusculan Disputations (book 3). In both cases he says that what happens is that (i) immature minds (i.e., those of children and the young) get confused when attempting to sort out impressions from the outside world; and (ii) their caregivers and the surrounding society—who themselves grew up with and are affected by similar confusions—do not clarify, and in fact further muddle, the young’s impressions. It is in this way that we end up valuing pleasure, power, reputation, and wealth instead of reason and prosociality, that is, virtue.

On the Laws is one of the early books in which Cicero begins to articulate his ethical thinking. Its main goal there is to argue that our codes of law are not arbitrary but attempt to reflect a natural law, what Graver calls “an untutored awareness of fairness and justice.” Cicero’s claim is rather minimal: Nature endows us with some instinctive thinking from which we then fashion our mature concept of justice.

However, we are also subject to “perversion” when we override our natural instincts due to “customs and false opinions” (On the Laws, 1.29). Cicero says that the mistake is caused by the fact that some things appear desirable or undesirable that are very close to what Nature teaches us actually should be desirable or undesirable. It is our inability to distinguish the two cases that causes the trouble.

For instance, pleasure is naturally sought and pain naturally avoided, but it is a mistake to think (as the Epicureans do) that pleasure is therefore the ultimate good, or pain the ultimate evil. Pain, for instance, often co-occurs with injuries, so we make the mistake of thinking that it is pain itself that is bad, and children especially are confused, which is why it is difficult to make them do anything that is good for them and yet painful, like taking a medicine. Similarly, Graver adds, an infant fails to realize that drinking milk and taking a bath are healthful, not just pleasurable.

Or consider honor and glory: according to Cicero, they resemble moral excellence, but they are not quite it, though honor and glory may come from recognized moral excellence:

“For real glory is a solid thing, clearly modeled and not shadowy at all: it is the unanimous praise of good persons. … But there is another sort of glory, which pretends to imitate the first, and which is rash and ill-considered, frequently praising misdeeds and faults. This is popular acclaim.” (Tusculan Disputations, 3.3-4)

Praise in general is a powerful type of positive reinforcement, but when we praise especially young people for the wrong things, we confuse and corrupt them. Similarly for, say, our quest for power, another widespread error among human beings. It is natural for us to want to control our environment, and power does increase our control. But it is control, not power, that is good, and it is an epistemic mistake to confuse the two.

Even life itself isn’t actually a good, only the preservation of our natural, healthy, state is. Which is why continuing life at all costs, regardless of its quality, is yet another epistemic error. In the end, Cicero focuses on six objects that we tend to mistakenly think are good or evil, and they come in pairs: pleasure and pain, death and life, honor and disrepute. Everything else he thinks stems from these three pairs.

Interestingly, in section 47 of the first part of On Laws, Cicero even makes an argument against relativism of the type that is still common today (at least, among my students): people think that because there are different opinions about moral issues then there is no natural law, anything goes (certainly the Pyrrhonists would think that way). But a divergence of opinion among people can be explained by the fact that some are simply mistaken on such matters, as a result of the corrupted education they receive.

Consider, for instance, an example from the natural sciences, a field that few people are inclined to treat relativistically. And yet, half of the American public rejects the well established theory of evolution in biology. It doesn’t follow from this that creationism and evolution are on the same epistemic level, your opinion my opinion. If you reject evolution and embrace creationism you are just wrong on the facts. And, in a further analogy with what Cicero has been talking about, you do so because of a combination of bad reasoning on your part and corrupting influences from your parents, preacher, and other members of your in-group.

Cicero’s ideas, as mentioned above, are rooted in more ancient Stoic thinking. We get a good summary of it from the commentator Diogenes Laërtius:

“The rational animal is corrupted sometimes by the persuasiveness of things from without, sometimes through the teaching of our associates. For the starting points which nature provides are uncorrupted.” (Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, 7.89)

The origin of the Stoic dual theory of moral error (i.e., external influences + internal mistakes), according to Graver is attributed by the physician-philosopher Galen (who lived at the time of Marcus Aurelius and was his personal doctor) to Chrysippus of Soli, in his now lost book, On Emotions:

“The cause of perversion is twofold: [it] comes about through transmission from many people … and the persuasiveness of impressions.” (Galen, On Doctrines of Hippocrates and Plato, 5.5.14)

That Chrysippus articulated such a dual theory of moral error is also confirmed by a later source, a commentary on Plato’s Timaeus by Calcidius, written around 400 CE:

“Since the happy person necessarily enjoys life, they think that those who live pleasurably will be happy. Such, I think, is the error which arises from things to possess the human mind. But the one which arises from transmission is a whispering added to the aforementioned error through the prayers of our mothers and nurses for wealth and glory and other things falsely supposed to be good.” (On the Timaeus of Plato, 165–166)

This notion that our natural abilities become corrupted and give rise to unintended (by Nature) side products is also deployed by modern psychologists like Pascal Boyer to explain the phenomenon of religion and of credence in the supernatural. In an article published in Skeptical Inquirer and entitled “Why is religion natural?” Boyer explains that the human mind has a number of built-in, presumably adaptive capacities such as a theory of mind (which allows us to attempt to understand what other people think) and a tendency to project agency (i.e., to assume that others have intentions and purposes). These capacities, however, can also produce superstitious beliefs that are otherwise not warranted, such as that natural phenomena are purposeful, or that there are gods with intentions and plans of their own.

In my opinion, the beginning of the process of corruption that gave rise to the problem of the perverse was the shift from a nomadic life of hunting and gathering to a settled life based on agriculture, a shift that took place during the Neolithic, starting about 11,700 years ago. This transition led to a marked demographic transition and the first known civilizations of the so-called “fertile crescent”—such as the Sumerian—about 6,500 years before the present. This led to the further transition from the Neolithic (“new stone age”) to the bronze age (which lasted until about 1,200 BCE) and finally to the iron age.

The so-called first agricultural revolution dramatically altered human evolutionary dynamics, transitioning humanity from the previous, long period of mostly biological evolution to the more recent, accelerating period of largely cultural evolution. It is no wonder that the tools that evolved slowly by bio-genetic means (i.e., our instincts) often misfire in a social environment for which they were not designed.

If this, admittedly speculative, scenario is even approximately correct, the answer cannot be to just go back to the pre-agricultural Pleistocene, when human beings lived in small groups of mostly relatives. The answer, if there is one, is to learn about the problem of the perverse and do our best to enact the only counter-measure we have devised so far: sound philosophical teaching and practice.

_____

[1] Yes, yes, I know, there are some who embrace the notion of panpsychism who will disagree. There are excellent reasons to think they are mistaken.

Thanks, Massimo! I’ve observed that the instincts, which evolved for a hunter gathering setting, often lead people to attribute malicious motives to the most mundane inconveniences and set backs. Perhaps conspiratorial thinking that has become widespread, despite the abundance of contrary facts, is due to these instincts being exploited by social media algorithms, cable news, demagogues, etc. It’s like a flaw in the system, which has been exploited to override the capacity for pro social tendencies and reason.

This article dives deep into the reactor core where the mysteries of the universe are harnessed to allow us to flourish on the surface of this beautiful Blue Marble. Chock Full O’Nuts, once again, Massimo. ☕️😊

The universe, whether “living” or “conscious,” or divine or providential, or fated by reason by way of cause and effect, “is” and therefore rational (if the meaning of the word rational can explain reality). However, did the universe endow us to be virtuous, or did it endow us the capability to be virtuous? I am ignorant as to exactly what the Stoics say, but it seems it would be redundant if it is both.

This article can stand as an introduction to a full year course. I cannot ask or comment about every sentence written in it, but I mainly agree, or follow, with most, if not all, of it. When it comes to human nature and the agricultural revolution and subsequent rise of civilization, it must have posed problems for our instincts. However, were our instincts always rational, reasonable and virtuous? If the ancestors of Homo sapiens weren’t risk averse, which can be said to lean on the side of irrational, or unreasonable, especially when it comes to actual life and death circumstances, would we have arrived in the now on this train of evolution? I suppose my point is that humans may not always act rationally. It’s difficult for them. And it might be in our genes to do so. Let’s forget for a moment nurturing and corrective behavior in rearing. We can go back and forth on that and cite the studies. But maybe somewhere in our genome risky and irrational behavior is ready to turn on? This then could fall under the domain of scientific. However, I believe in the power of intelligence and that our minds can overcome almost all adversity—most certainly if we apply our judgements. I believe the simple logic of Stoicism is a sublime guide. I don’t disagree with your premises, I just want to know more. I need to in order to share what I learn with others. 😊