The story of the pale Stoic in the storm

Stoicism and fear, from the lost Fifth Book of Epictetus

Fear is a basic human emotion. Or is it? It depends on what you mean by “fear.” Modern cognitive science recognizes two different forms of most basic emotions: a pre-cognitive and a cognitive one. In the case of fear, for instance, the pre-cognitive form consists in the feeling you get when an autonomic physiological response is initiated by situations your brain subconsciously recognizes as potentially dangerous. It’s that rush of adrenaline that poises you to act on the fight-or-flight response triggered by your sympathetic nervous system. We share such response with a lot of other animals, and it likely evolved by natural selection.

The cognitive version of fear either follows the fight-or-flight response, once you have had time to think things over, or is an independent, long-term psychological condition. An example of the first kind might be a fight-or-flight condition triggered, say, by suddenly seeing a snake in front of you. After a moment or two the cognitive component starts weaving stories in your conscious brain: “Oh my god, this thing is likely poisonous. It’s going to kill me!” But you have the option of articulating a different story: “Ah, I have read about snakes in this area, and they are usually not poisonous. Besides, the ranger at the entrance of the park has given me instructions on what to do in exactly this situation.” The first story is going to turn your autonomic fight-or-flight response into cognitive fear; the second story will counter it and allow you to deal rationally with the situation.

Long-term psychological fears also have a cognitive component, but they do not originate from a fight-or-flight situation. They result from persistent narratives you tell yourself as a result of other people’s influences, what you read, what you watch on television, and what you see on social media. For instance, you may be afraid of a terrorist attack, even though in most places in the world the chances of this actually occurring are minuscule.

The Stoics drew a distinction between pre-cognitive and cognitive emotions, for instance Seneca, in On Anger, refers to pre-cognitive emotions as “the first movement” that may, or may not—depending on how we act—lead to the full fledged version. He counts blushing as another example of pre-cognitive emotion. Epictetus calls our first reaction an “impression,” to which—if we take our time—we may or may not give “assent,” thus allowing the pre-emotion to proceed to cognitive emotion.

Yet another way of thinking about this is in terms of Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, who in his best-selling Thinking, Fast and Slow, talks about two gears for our brain: System I, which is subconscious, fast, but approximate; and System II, conscious, reliable, but slow. Although there are situations that unfold so quickly that our only choice is to rely on System I, Epictetus’s advice is to, whenever possible, pause and allow System II to come on, so that we can properly question our first impression and see whether we do wish to act on it or not.

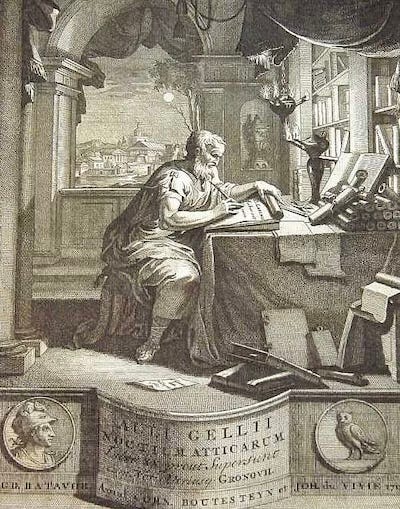

I’m telling you all of this because the other day, in the middle of an online discussion for a course I’m teaching on Seneca’s Letters, one of my students brought up a classic instance of the difference between impressions and assent in the Stoic literature, a story told by Aulus Gellius (125-180) in his Attic Nights (specifically, at 19.1). I’m going to transcribe the full (fairly long, sorry!) passage and intersperse a bit of commentary, as needed. It begins thus:

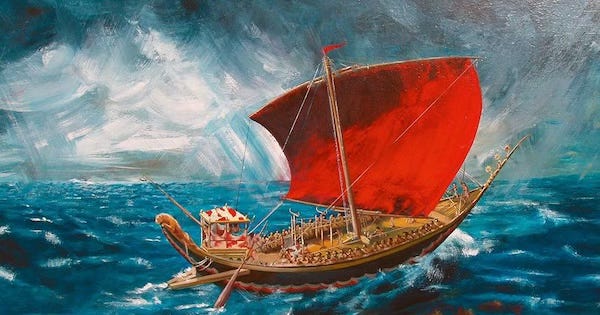

“We were sailing from Cassiopa to Brundisium over the Ionian sea, violent, vast and storm-tossed. During almost the whole of the night which followed our first day a fierce side-wind blew, which had filled our ship with water. Then afterwards, while we were all still lamenting, and working hard at the pumps, day at last dawned. But there was no less danger and no slackening of the violence of the wind; on the contrary, more frequent whirlwinds, a black sky, masses of fog, and a kind of fearful cloud-forms, which they called typhones, or ‘typhoons,’ seemed to hang over and threaten us, ready to overwhelm the ship.”

Cassiopa was a town in the north-eastern part of Corcyra, modern Corfu, near the northwestern border of Greece. Aulus is setting the dramatic scene here, letting us feel the senario: a powerful storm is battering the ship at night, and it does not abate the following day.

Notice the use of the word “typhoon” to describe the storm. Typhon was a gigantic monster in the form of a serpent, and one of the most deadly creatures in all of Greek mythology. According to Hesiod, he was the son of Gaia (the personification of Mother Earth) and Tartarus (the deep abyss where the Titans and wicked souls are imprisoned and tortured). Aulus continues:

“In our company was an eminent philosopher of the Stoic sect, whom I had known at Athens as a man of no slight importance, holding the young men who were his pupils under very good control. In the midst of the great dangers of that time and that tumult of sea and sky I looked for him, desiring to know in what state of mind he was and whether he was unterrified and courageous. And then I beheld the man frightened and ghastly pale, not indeed uttering any lamentations, as all the rest were doing, nor any outcries of that kind, but in his loss of color and distracted expression not differing much from the others.”

Aulus turns to look at the unnamed Stoic onboard because he is curious whether the Stoics’ reputation for courage and control of their emotions is true. At least initially, he is disappointed, because the philosopher in question is pale and appears frightened. However, notice that the Stoic is not given to outcries of fear, as many of the others are. This will become significant a bit later.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Philosophy Garden: Stoicism and Beyond to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.