In The Picture of Dorian Gray Oscar Wilde has the character of Lord Henry say to Dorian that “The only thing worse than being talked about is not being talked about.” Then again, Henry was a cynical hedonist, so we should probably take his advice with a fairly large grain of salt.

It certainly does not apply to Stoicism, which these days is often being talked about in ways that distort the philosophy and undermine its usefulness. The thought came back to my mind last week, when I saw a cartoon by Corey Mohler, the author of the brilliant Existential Comics. Comic strips are often considered low brow and certainly beneath the attention of serious students of philosophy. And yet, I think I could teach an entire course on the subject using only Corey’s cartoons. Indeed, I just might, one of these days.

Corey’s cartoon n. 484 begins with the two panels reproduced (with permission) above: some 21st century guy reaches out to the second century Stoic philosopher Epictetus and tells him that his philosophy has become very popular in the future. Would he want to see it? The sage from Hierapolis is not surprised, responding that “I always knew Stoic virtue is the way to live.”

Epictetus actually rarely talked about virtue, a concept that was more frequently deployed by earlier Stoics, from the founder of the sect, Zeno of Citium, to Epictetus’ near contemporary, Seneca. Rather, his philosophy focused on five basic ideas (discussed in more details here):

I. The fundamental rule of life: the notion that some things are up to us and others are not, and that a good life is the result of focusing on the first class while cultivating an attitude of acceptance and equanimity toward the second class.

II. Opinions are not facts: facts are objective, mind-independent features of the world, while opinions are the result of human judgments. We would do well to keep this distinction in mind because it is our opinions, not the facts themselves, that so often upset us.

III. There are three areas (so-called disciplines) in which we need to train ourselves in order to live an ethical life: (a) re-orienting our priorities toward what is truly good and away from what is truly bad (as opposed to what society tells us is good or bad); (b) acting justly toward our fellow human beings; (c) refining our judgments so that they are correct as frequently as possible.

IV. We should embrace an ethos of cosmopolitanism, according to which other human beings are like brothers and sisters.

V. We need to pay attention to our thoughts and actions, because things are generally not improved by not paying attention.

Keep the list above in mind because it will allow us to appreciate why Corey’s cartoon is very much on target in its criticism of much contemporary Stoicism.

The next three panels in the cartoon (above) identify three of the more widespread varieties of bad Stoicism out there: using the philosophy to advance one’s career, succeed in having sex, and make money. But what’s wrong with these goals, exactly?

They have absolutely nothing to do with Stoicism. See if you can spot a clue in what Epictetus says at the beginning of the Enchiridion:

“Some things are up to us and some are not. Up to us are judgment, inclination, desire, aversion—in short, whatever is our own doing. Not up to us are our bodies, possessions, reputations, public offices—in short, whatever isn’t our own doing.” (Enchiridion 1.1)

Externals like health, wealth, career, reputation, and so forth are not up to us, and therefore we should not concern ourselves with them, says Epictetus. And yet those are precisely the sort of things that so many self-professed gurus of Stoicism keep telling us we can use the philosophy to obtain. (No, I will not name names, I’m sure you’re smart enough to easily figure it out on your own.)

Externals are classed by Stoics as “indifferent,” meaning that they make no difference to the only thing that matters: the betterment of our character, which is accomplished by paying attention to and improving our judgments. Here, for instance, is Epictetus on money:

“‘Get money, then,’ someone says, ‘so that we can have some too.’ If I can get it while retaining my self-respect, trustworthiness, and high-mindedness, show me the way and I’ll get some. But if you’re asking me to lose my good qualities so that you can get things that aren’t even good, you can see how unfair and unfeeling you’re being. What would you rather have, money or a trustworthy and self-respecting friend?” (Enchiridion 24.3)

And here he is talking about lust:

“It is not a [rational] judgment that makes them incapable of resisting lust and turns them into adulterers and seducers, or makes them commit all the other crimes that people can commit against one another. All this is the outcome of just one judgment alone—the location of themselves and all they are in externals, things that aren’t subject to will.” (Discourses 2.22.28)

People who think it’s great to casually seduce others into having sex with them are using others for their own ends, disrespecting them as human beings. And they mistakenly think this is good because they are confused about what is and is not good. They go after externals instead of pursuing ethical self-improvement.

What about our career? That too is an external, and if we salivate after externals we willingly make ourselves the slaves of whoever happens to be in a position to grant them to us (Discourses 4.1.59). So when we hear businessmen trumpeting Stoicism as a way to become successful, or coaches telling their athletes that Stoicism will help them win the game, we are hearing bullshit that has nothing to do with the actual philosophy. A Stoic, according to Epictetus, simply does not consider success and reputation things that are worth being concerned with, let alone things that define who we are.

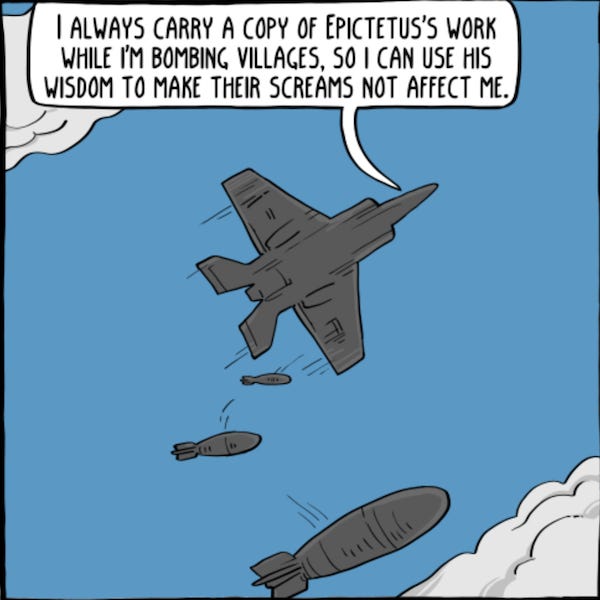

The next panel in Corey’s cartoon (above) is the most controversial. It features an unseen fighter pilot who claims that he carries a copy of Epictetus’ Enchiridion with him every time he goes out on a mission to bomb innocent people. The not so subtle reference is to James Bond Stockdale, former Vice Presidential candidate (with Ross Perot, in 1992), Vice Admiral of the US Navy, and decorated war hero.

Stockdale is often presented as a role model for modern Stoics, a kind of contemporary version of Cato the Younger, the Roman Senator so admired by Seneca. The reason for this is that Stockdale was famously shot down during the Vietnam War and in his memoirs credited Epictetus with saving his life. He had studied Epictetus and did, in fact, carry a copy of the Enchiridion with him. When his plane was hit he parachuted himself out of the cockpit and saw that he was about to be apprehended by the enemy. He told himself that he was going to “enter the world of Epictetus,” meaning that he would essentially be a slave for at least five years. Turns out, he had been optimistic: he spent the years between 1965 and 1973 in the so-called Hanoi Hilton, a high security Vietnamese prison for enemy combatants. He was tortured and occasionally put in isolation, but survived by keeping firm in mind the above mentioned fundamental rule of life, the distinction between what was up to him (very little) and what was not (a lot).

Sounds good, right? The problem is that that’s not the whole story. On August 4, 1964 Stockdale was flying a mission in the Gulf of Tonkin. He was there during the infamous incident that US President Lyndon Johnson used as an excuse for commencing full scale hostilities against North Vietnam. Except that there was no incident at all. And Stockdale knew it. Later on he wrote:

“[I] had the best seat in the house to watch that event, and our destroyers were just shooting at phantom targets—there were no PT boats there. ... There was nothing there but black water and American fire power.” (Essay on the 40th Anniversary of the Gulf of Tonkin Incident)

When the next morning Johnson ordered the first bombing raids in retaliation for the attack at Tonkin, Stockdale’s comment was: “Retaliation for what?” Nevertheless, he said nothing and dutifully participated in a war that he knew perfectly well had been started on false pretenses.

Would that be the behavior of a Stoic? I don’t think so, and the current fashion of connecting Stoicism with the military in this manner is a particularly pernicious one. In order to understand why, let us dispose of two standard arguments advanced by supporters of the notion that Stockdale should be considered a Stoic role model.

The first argument is that an ancient Stoic would not have a problem with war. Just think of the above mentioned Cato and, of course, of the emperor-philosopher Marcus Aurelius. This is fallacious reasoning on multiple counts.

To begin with, both Cato and Marcus engaged in what they considered just wars. The notion of a just war is not an oxymoron, and in fact the Romans were instrumental in articulating the concept, which is still at the center of our ethical thinking about conflict. In Cato’s case, he picked up arms against Julius Caesar because he thought Caesar was a tyrant bent on destroying the Roman Republic (he was right). As for Marcus, he waged defensive wars against the Parthians on the eastern frontier and the Marcomanni and other German tribes on the northern frontier, and moreover he attempted diplomatic solutions whenever they seemed feasible. This is clearly different from the US intervention in Vietnam, which no scholar or sane person could possibly regard as an example of just war (in modern times, pretty much only the first and second world wars may qualify, with caveats).

Regardless, the important point really isn’t what this or that ancient Stoic did, but rather what the philosophy of Stoicism logically entails, and therefore how a modern Stoic may reasonably practice it. This was made clear by one of the best studies of ancient vs contemporary Stoicism to date, a paper entitled “Stoicism, Feminism and Autonomy,” authored by Scott Aikin and Emily McGill and published in the journal Symposion in 2014.

Aikin and McGill asked themselves two related questions: (i) Were the ancient Stoics feminist? (ii) Does Stoicism as a philosophy logically entail feminism, understood minimally as the notion that women ought to have equal rights with men?

They answered the first question in the negative, despite the well known fact that several ancient Stoics (Seneca, Epictetus) explicitly acknowledged that women are just as capable as man of studying philosophy and practicing virtue. Correctly, Aikin and McGill argued that that’s insufficient to meet the modern definition of feminism, unsurprisingly. However, they also, again correctly in my opinion, argued that Stoicism as a philosophy does imply feminism because of the Stoic notion of cosmopolitanism and because of the Stoic virtue of justice (which is understood as treating others fairly and with respect).

This brings us to the second argument often advanced by those who are sympathetic to the idea that Stockdale is a Stoic role model: the claim that Stoicism does not entail pacifism. This is certainly true. The ancient Stoics were not pacifists, and I don’t see anything in Stoic philosophy that logically implies pacifism. Just in the same way that if you, as a Stoic, are personally violently attacked you are perfectly within your rights to defend yourself with violence, so is the case that your country is attacked you have a right to help your fellow citizens defend themselves against the aggressor.

However, Stoic cosmopolitanism seems to me wholly incompatible with any kind of aggressive or unjust war, because such a conflict would ignore the notion of a universal human brother/sisterhood. In fact, Stoicism explicitly teaches us to treat people who do bad things as if they were sick: they should not be punished, but helped, once they are put in a position not to hurt innocents. Here is Epictetus on the theme, in conversation with one of his students:

“‘But shouldn’t a thief or an adulterer be eliminated, just for being who he is?’ No, and you’d do better to phrase your question like this: ‘Should we do away with this person because he’s mistaken and misled about matters of supreme importance, and because he’s become blind—not in the sense that he’s lost the ability to distinguish white and black by sight, but because he’s lost the mental ability to distinguish good and bad?’ If you put the question like this, you’ll realize how inhumane it is, and see that it’s no different from saying, ‘So shouldn’t we kill this blind person, or this deaf person?’ If a person is injured most by the loss of the most important things, and if the most important thing in every individual is right will, what’s the point in getting angry with someone if he loses it?” (Discourses 1.18.5-8)

Epictetus’ point is that we should regard other people’s bad actions as being the result of lack of wisdom, which is a disease of the will. We ought to aim to cure such disease, if possible, and definitely not get angry or pursuit revenge against the offenders. I cannot imagine how any aggressive or otherwise unjust war would not violate this principle, which the Stoics derive directly from Socrates.

Therefore, since Stockdale willingly fought an unjust war, and moreover knew that the war was started under false pretense and yet said nothing, he cannot possibly be considered a Stoic role model.

Why do we see this unfortunate proliferation of bad varieties of Stoicism in the first place? Because people confuse life hackery for philosophy. Take again the Stockdale case: it is certainly true that he was using a technique derived from Epictetus in order to survive his ordeal as a prisoner of war. But he wasn’t being true to Epictetus’ philosophy, which runs contrary the whole idea of the sort of conflict in which Stockdale voluntarily participated.

The same goes for the sort of “Stoics” depicted in the earlier panels of Corey’s cartoon: yes, one can certainly deploy Stoic practices with the goal of getting rich, advancing one’s career, or picking up women (or men, or other). But one is not thereby practicing Stoicism as a philosophy of life.

This sort of decoupling between life hackery and philosophy affects other systems of thought, not just Stoicism. For instance, different kinds of Buddhist-inspired meditations have been found to be effective for a range of issues, from calming one’s mind to managing chronic pain. But the practice of meditation does not make one a Buddhist. And indeed lots of Buddhists do not, in fact, meditate. What makes one a Buddhist is an acceptance of the Four Noble Truths and a sincere adherence to the Eightfold Path.

Similarly with Stoicism: by all means, apply the fundamental rule of life, pay attention to whatever you are doing, keep a journal of your experiences, and engage in an occasional sunrise meditation. None of this, as useful as it may be, will make you a Stoic. Adopting the five pillars of Epictetus’ philosophy as summarized above will.

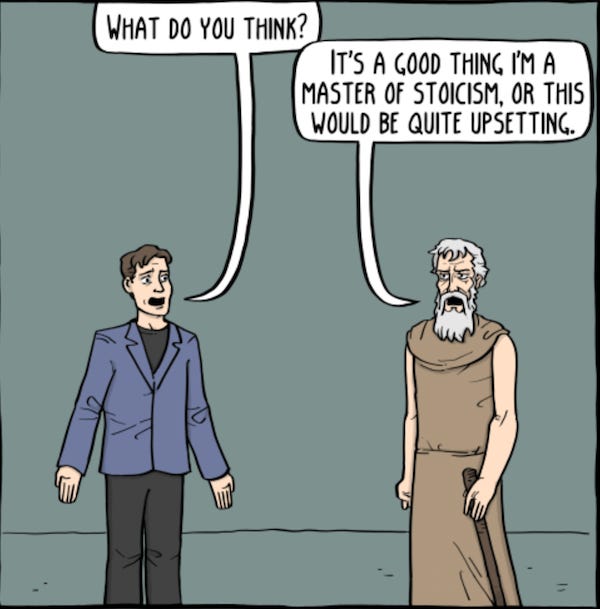

Speaking of Epictetus himself, as he points out in the last panel of Corey’s cartoon (below), it’s a good thing he’s a Stoic, or he would be quite upset by the distortions and misuses of his philosophy that are being bandied around in the 21st century.

Thanks Massimo. Stockdale was never one of my role models, but that aside, you pinpoint what about his behavior was problematic. His behavior after the Gulf of Tonkin was indeed blameworthy. I don't fault him on not living up to an ideal sage, but I don't recall that he ever fully acknowledged his complicity in the pentagon war machine enough to prevent doing the same thing in the future. Thanks for the essay.

Yes, i’m afraid it can. And has. Can’t wait!