Tracking Plato and Cicero in Syracuse

Random notes from the greatest and most beautiful of “Greek” cities

I am writing this while sitting in an Airbnb apartment in Ortigia, the beautiful island that is part of the greater city of Syracuse, in Sicily. I’m here with my wife as part of our sabbatical from the City University of New York. She is writing a novel set in the American midwest during World War II. I am writing a book on Cicero and co-authoring another one on practical Hellenistic philosophies (together with my friends Greg Lopez and Meredith Kunz).

One reason to come to Syracuse was to “track down,” so to speak, Cicero, who was Quaestor of Sicily in 75 BCE, aged 31. This was the first step in his cursus honorum, the series of political offices that eventually culminated with his consulship in 63 BCE. Indeed, several other stops during my sabbatical are related to Cicero: Rome, of course; western Turkey (he was governor of Cilicia, in the southern coast of modern Turkey); and Athens, where he went several times during his life to study or simply get away from the sometimes turbulent affairs of the capital, not to mention to visit his lifelong friend, Atticus.

Cicero visited Syracuse and described it (in his oration Against Verres) as “the greatest Greek city and the most beautiful of them all.” He spent time here trying to find the lost tomb of Archimedes, and succeeded in doing so, as he tells us in some detail:

“I will present you with a humble and obscure mathematician of the same city [Syracuse], called Archimedes, … whose tomb, overgrown with shrubs and briers, I in my quæstorship discovered, when the Syracusans knew nothing of it, and even denied that there was any such thing remaining; for I remembered some verses, which I had been informed were engraved on his monument, and these set forth that on the top of the tomb there was placed a sphere with a cylinder. When I had carefully examined all the monuments (for there are a great many tombs at the gate Achradinæ), I observed a small column standing out a little above the briers, with the figure of a sphere and a cylinder upon it; whereupon I immediately said to the Syracusans—for there were some of their principal men with me there—that I imagined that was what I was inquiring for. Several men, being sent in with scythes, cleared the way, and made an opening for us. When we could get at it, and were come near to the front of the pedestal, I found the inscription, though the latter parts of all the verses were effaced almost half away. Thus one of the noblest cities of Greece, and one which at one time likewise had been very celebrated for learning, had known nothing of the monument of its greatest genius, if it had not been discovered to them by a native of Arpinum [Cicero’s birthplace].” (Tusculan Disputations, V.23)

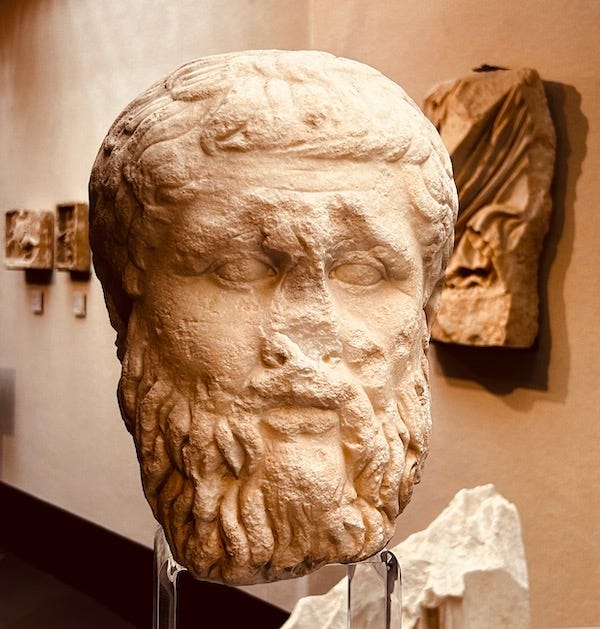

On our way here from Rome, though, it occurred to me that, of course, another great philosopher of antiquity had spent considerable time in Syracuse, on multiple occasions: Plato. As he himself says in his Seventh Letter (allegedly, since the authorship of the document has been questioned), he came to Sicily three times in order to convince first Dionysius I and then Dionysius II, tyrants of Syracuse, to adopt philosophy as a way of life and implement a just government in the city.

Plato made his first trip in 387 BCE, in his early forties, at the invitation of Dionysius I. The tyrant wanted to embellish his court, attempting to surround himself with men of repute. Plato, on his part, wanted to visit Mt. Etna, and probably also saw an occasion to try out some of his ideas in political philosophy, if only he could convince Dionysius to listen.

It didn’t go well: annoyed by Plato’s frank criticism, Dionysius I sold the philosopher into slavery, and Plato had to be rescued by his friends, who had to pay for his release. But the trip wasn’t a total waste, as Plato met Dion, Dionysius’s brother in law, who was far more receptive to philosophical training and became one of Plato’s students.

When Dionysius I died his son, Dionysius II, took over. He initially showed promise of being an enlightened ruler, and reportedly developed a passion not just for philosophy, but for Plato in particular. This prompted Dion to invite Plato back to Syracuse, in 367 BCE. The philosopher was now in his early sixties, and yet eagerly embarked on what was at the time a fairly perilous journey, especially for a man who was, by the standards of ancient Greece, rather old.

The problem was that Dion had a number of political enemies at court, who were jealous of his, and Plato’s, influence on Dionysius II. They spread rumors of a conspiracy against the tyrant, as a result of which Dion was sent into exile to the Peloponnese and Plato was temporarily imprisoned in Ortigia’s citadel, probably not far from where I’m currently living.

But the story ain’t over yet! Dionysius II changed his mind again about philosophy, and wanted Plato back. He decided that the best way was to engage in some good old fashioned blackmail. Since Plato was a friend of Dion, Dionysius II wrote to the philosopher: “No mercy would be shown to Dion unless Plato were persuaded to come to Sicily; but if he were persuaded, every mercy.” So Plato arrived in Syracuse a third time, in 362 BCE, in his mid-sixties.

Once again, however, Dionysius II proved fickle and incorrigible, and Plato had to beat a hasty retreat from Syracuse, for the last time. Back in Athens, Plato travelled to the Olympic Games of 360 BCE, where he met Dion and told him the story.

By now Dion had had his fill of Dionysius, who had stolen his money and property and even married his wife to another man. He raised an army (or, according to Plutarch, a small but determined band) and landed at Syracuse in 357 BCE, helped by Speusippus and a number of other members of Plato’s Academy (but not Plato himself, who had philosophical objections to the notions of revenge and of violent toppling of a government).

Taking advantage of the fact that Dionysius II was out of the city on a military campaign, Dion secured the town and managed to establish a new government. His success, however, did not last long, as he found himself at odds with a populist named Heracleides, who took advantage of the Syracusans’ lack of trust of Dion and drove him into exile once more.

In 355 BCE Dionysius II attempted to conquer the city anew, and the terrified inhabitants reached out to Dion to come to their defense. Which he did, successfully defeating the former ruler. But factionalism within the city continued unabated, and things were not helped by the fact that apparently Dion himself had a bit of an authoritarian streak. It seems that Syracuse was continually exchanging one tyrant for another. Dion was betrayed by one of Plato’s students, Callipus, who entered his house and assassinated him. Talk about practical philosophy!

Dionysius II came back once more, and ruled Syracuse until he was finally permanently exiled by the Corinthian Timoleon, who established a democratic government in 344 BCE. That, of course, was not the end, but at this point we are getting pretty far from Plato, who had died four years earlier, aged 80.

There is another fascinating story about Dionysius II, told by Cicero, and which my grandfather related to me when I was a child: the tale of Damocles’s sword. Here is how Cicero recounts things:

“This tyrant [Dionysius II], however, showed himself how happy he really was; for once, when Damocles, one of his flatterers, was dilating in conversation on his forces, his wealth, the greatness of his power, the plenty he enjoyed, the grandeur of his royal palaces, and maintaining that no one was ever happier, ‘Have you an inclination,’ said he, ‘Damocles, as this kind of life pleases you, to have a taste of it yourself, and to make a trial of the good fortune that attends me?’ And when he said that he should like it extremely, Dionysius ordered him to be laid on a bed of gold with the most beautiful covering, embroidered and wrought with the most exquisite work, and he dressed out a great many sideboards with silver and embossed gold. He then ordered some youths, distinguished for their handsome persons, to wait at his table, and to observe his nod, in order to serve him with what he wanted. There were ointments and garlands; perfumes were burned; tables provided with the most exquisite meats. Damocles thought himself very happy. In the midst of this apparatus, Dionysius ordered a bright sword to be let down from the ceiling, suspended by a single horse-hair, so as to hang over the head of that happy man. After which he neither cast his eye on those handsome waiters, nor on the well-wrought plate; nor touched any of the provisions: presently the garlands fell to pieces. At last he entreated the tyrant to give him leave to go, for that now he had no desire to be happy. Does not Dionysius, then, seem to have declared there can be no happiness for one who is under constant apprehensions?” (Tusculan Disputations, V.21)

I took a break from writing this essay and went down to the port of Ortigia, nowadays full of delightful places where you can sit down, order a spritz aperitivo, which is served with prosciutto and cheese or bruschetta, and watch the people and the boats go by.

While I was looking over the calm waters my mind was transported back in time to one of the greatest and most terrifying events Syracuse has ever witnessed: the arrival of the Athenian fleet in 415 BCE, with the intent of opening a second front of the Peloponnesian War against Sparta. The Athenians suddenly showed up at the entrance of Syracuse’s port with 134 triremes, 5100 hoplites, 480 archers, 700 slingers, 120 other light troops, 30 cavalry, and 130 other supply ships. These were later supplemented by an additional 73 ships and 5000 hoplites.

It was all for nothing. Two years later, in 413 BCE, the Athenian fleet was utterly destroyed by the Syracusans, and their army was either killed or captured and enslaved. All things considered, Athens lost 10,000 hoplites and 30,000 horsemen, a loss that contributed a great deal toward the final defeat in the war, which in turn paved the way for the rise of Macedonia and the meteor that was Alexander the Great.

And speaking of naval battles, and I promise, this is the last story for today! Ortigia is connected to the mainland by two bridges, Ponte Umbertino and Ponte Santa Lucia. In between them lies a modern statue of Archimedes, who was a native Syracusean.

Archimedes’ accomplishments are numerous: he derived an approximation of Pi (which is why you’ll see the Greek letter everywhere in Syracuse), anticipated modern calculus, produced a proof of the law of the lever (he famously said “give me a point of leverage and I will lift the world”), and enunciated the law of buoyancy (which led to him running in the city streets yelling “Eureka!”).

One of his engineering accomplishments was (allegedly) a death ray. I’m not kidding. He figured that he could use parabolic mirrors, probably made of bronze or copper, to concentrate sun rays onto oncoming ships, setting them on fire. The second century commentator Lucian of Samosata tells us that Archimedes put his invention to practical use during an attempted Roman invasion. Perhaps it wasn’t by chance, then, that later on a Roman soldier killed Archimedes on the spot, even though he had explicitly been told to capture the genius alive. The Romans knew quite a bit about engineering, as well as the value of imported talent.

Beautiful story ❤️

Thank you for taking us along!