Why Epicureans and Utilitarians are wrong: on the axiology of pain and pleasure

Moral philosophers are beginning to incorporate insights from evolutionary biology

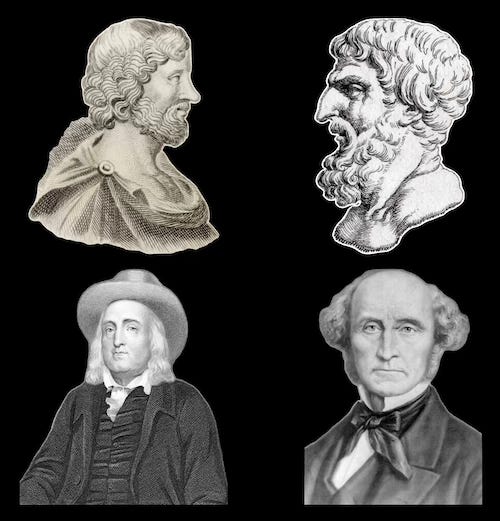

Hedonism, philosophically speaking, is “the ethical theory that pleasure (in the sense of the satisfaction of desires) is the highest good and proper aim of human life.” (Apple Dictionary) Two major clusters of hedonistic theories appeared in the history of western philosophy: the Cyrenaics and Epicureans of Hellenistic times, and the Utilitarians of the 19th to the 21st centuries.

Cyrenaicism was a short-lived school established by Aristippus of Cyrene (modern Libya, north Africa) who was born around 435 BCE and was, interestingly, a student of Socrates—himself certainly not an hedonist. The Cyrenaics believed that the good life consists in experiencing physical pleasures in the present, largely rejecting both intellectual pleasures (because they are less intense) and pleasures that were from the past (enjoyed merely by remembering them) or the future (not here yet, and may never come). Not surprisingly, they also believed that pain is the only evil.

The Epicureans were a bit more sophisticated. They shifted the emphasis to moral and intellectual pleasures, like those we experience when we are in the company of friends, while retaining a lesser value for simple physical pleasures, like eating cheese and bread. Epicurus, who was born in 341 BCE and hence belonged to a later generation, was particularly preoccupied with the evils of pain, which gets in the way of the best life, one where we experience tranquillity of mind (ataraxia). Epicureanism still counts as a hedonistic school, though, in part because Epicurus identified lack of pain as the highest possible pleasure.

Nineteen century Utilitarianism was influenced by Greco-Roman hedonism and took two forms, which still reverberate in modern times. Jeremy Bentham thought that we should apply a universal hedonic calculus with the goal of maximizing most people’s pleasure and minimizing most people’s pain. Here is how Bentham himself described his famous principle of utility:

“Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do.… By the principle of utility is meant that principle which approves or disapproves of every action whatsoever according to the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interest is in question: or, what is the same thing in other words to promote or to oppose that happiness. I say of every action whatsoever, and therefore not only of every action of a private individual, but of every measure of government.” (An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, 1780)

Notice the shift from the typical virtue ethical focus on the individual and their personal flourishing to the social level, with mention of “every measure of government.”

John Stuart Mill was the second important contributor to the philosophy of Utilitarianism. He saw a problem in Bentham’s version similar to what, likely, Epicurus saw with Aristippus’s philosophy: the emphasis on purely quantitative measures of pleasure will likely lead to a dominance of physical pleasures at the expense of intellectual ones, and possibly to an emphasis on immediate satisfaction as distinct from a long-term view of things. So Mill introduced his famous distinction between “higher” and “lower” pleasures, reminiscent of the difference between Epicureanism and Cyrenaicism, respectively:

“It is quite compatible with the principle of utility to recognize the fact, that some kinds of pleasure are more desirable and more valuable than others. It would be absurd that while, in estimating all other things, quality is considered as well as quantity, the estimation of pleasures should be supposed to depend on quantity alone.” (Utilitarianism, 1863) [1]

For some time now I thought that there is a fundamental problem with pretty much all forms of hedonism: while it is true that nature gave us pleasures and pains as, respectively, incentives and disincentives to do things, it is just as clear—from the point of view of evolutionary biology (my original academic discipline)—that pleasures and pains cannot be intrinsic or ultimate goods, but only instrumental ones.

Evolutionarily speaking, for instance, pain is there to alert us to injuries that, if unattended, could cause long-term disability or death. Pleasure is there to entice us to do things we otherwise might not do, like engaging in the biologically all-important activities of courtship and sex (which are otherwise expensive in terms of time and resources). Put this way, it is clear what the only ultimate goods that nature set for us (and for all living organisms) are: survival and reproduction. [2]

Recently, philosophers seem to have picked up on the evolutionary angle as well. For instance, consider a paper by Alycia LaGuardia-LoBianco & Paul Bloomfield entitled The Axiology of Pain and Pleasure, published in the Journal of Value Inquiry (here is a short summary published at the New Work in Philosophy Substack).

My dictionary defines axiology as the study of the nature of value and valuation, and of the kinds of things that are valuable. One of the central questions in axiology is: what elements can contribute to the intrinsic value of a state of affairs? As an example, all consequentialists start with an axiology which tells us what things are valuable or fitting to desire. The word itself comes from the Greek axia, meaning “worth, value.” Interestingly, the Stoics famously referred to “externals,” that is, things that are not virtue, as having axia and therefore as being preferred or dispreferred.

Now, the standard hedonist axiological reasoning goes something like this: “Pain feels bad, so it must be bad; pleasure feels good, so it must be good.” But these, LaGuardia-LoBianco and Bloomfield point out, are epistemic mistakes: feelings are not necessarily a reliable guide to truth.

Let me give you one of my favorite examples of this from a story I read some time ago, I think in the New York Times. The author of the article, a woman, was on a first date and she didn’t think it was going too well. At some point, though, she felt “butterflies” to her stomach, the kind of sensation she usually associated with excitement. She thought, hmm, maybe this date is going better than I realized, or so my own feelings seem to tell me.

Then she dashed to the restroom to vomit. Turns out she had food poisoning, and that’s what her body was trying to tell her. So, no, your feelings are not necessarily a reliable guide to the truth!

Back to the axiology of hedonism. Hedonists, such as both Epicureans and Utilitarians, may grant that occasionally the experience of pain leads to good results, or the experience of pleasure to bad ones. For instance, going to the gym may be painful, both physically and mentally, but it brings long-term health benefits, again both physical and mental. Contrariwise, sitting on the couch and eating junk food may feel pleasurable in the moment, but it has long-term negative effects. Still, hedonists insist that pain is ultimately or intrinsically bad and that pleasure is ultimately or intrinsically good. In response, LaGuardia-LoBianco and Bloomfield write:

“We motivate an error theory of the value of pain and pleasure according to which arguments for pain’s intrinsic disvalue and pleasure’s intrinsic value rest on a mistake. This mistake arises from the commonplace association between what is painful and what is bad.”

And they continue:

“We argue that we should understand pain and pleasure through their role in evolution, as mechanisms which, when functioning properly, motivate us to avoid what is bad for us and do what is good for us. … Given this evolutionary perspective, the value of pain and pleasure is always and purely instrumental.”

That’s right: evolution, baby! This is a very good example, in my mind, of how the sciences and the humanities—in this case evolutionary biology and moral philosophy—can interact synergistically. It’s not that moral philosophy gets “reduced” to biology, but rather that one discipline illuminates things in the other, providing a different perspective that leads to novel, unexpected conclusions.

That said, the ancient Stoics (who also believed in the synergism of science, logic, and ethics) got to a similar conclusion without knowing anything about evolution. They just needed a general understanding of what Nature does. In book III of Cicero’s De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum (what a marvelous title: On the Ends of Good and Evil!), the character of Cato the Younger, a friend of Cicero, explains the Stoic system. He contrasts it with the Epicurean view by way of what is referred to as the “cradle argument.” Here is how it goes, in part:

“It is the view of those whose system I adopt, that immediately upon birth (for that is the proper point to start from) a living creature feels an attachment for itself, and an impulse to preserve itself and to feel affection for its own constitution and for those things which tend to preserve that constitution; while on the other hand it conceives an antipathy to destruction and to those things which appear to threaten destruction. In proof of this opinion they urge that infants desire things conducive to their health and reject things that are the opposite before they have ever felt pleasure or pain; this would not be the case, unless they felt an affection for their own constitution and were afraid of destruction. But it would be impossible that they should feel desire at all unless they possessed self-consciousness, and consequently felt affection for themselves. This leads to the conclusion that it is love of self which supplies the primary impulse to action. Pleasure on the contrary, according to most Stoics, is not to be reckoned among the primary objects of natural impulse.” (III.5)

This is just astounding: the human animal is endowed by Nature (i.e., we would say, evolution) with a strong instinct for self-preservation. Pain and pleasure are only signposts that guide our actions, but we both instinctively and, later on, consciously, sometimes do things that are painful, or avoid things that are pleasurable, because they would undermine our self-preservation. “Virtue,” that is, reason-based cooperative behavior, is a primary means of survival and—if the conditions are right—flourishing. That is, virtue is an evolutionary strategy.

Now, LaGuardia-LoBianco and Bloomfield are cautious in their evolution-based criticism of hedonism, claiming that their objection does not thereby completely invalidate hedonistic theories, but I think they don’t go far enough. They say:

“[The hedonists’] axiology of pain and pleasure’s values need refinement: what ought to be maximized are not pleasures per se, nor ought pains per se to be minimized, but rather good pleasures alone are maximized while bad pains alone are minimized.”

Right, but once we introduce the concepts of “bad” pains and “good” pleasures and pains the hedonist is left with no principled way to make distinctions between good and bad varieties of either. At least, not without renouncing hedonism in the first place.

_____

[1] In order to further justify his differentiation between high and low pleasures Mill famously added: “It is better to be a human dissatisfied than a pig satisfied; better to be Socrates dissatisfied than a fool satisfied. And if the fool, or the pig, are of a different opinion, it is because they only know their own side of the question. The other party to the comparison knows both sides.” (Utilitarianism, ch. 2)

[2] Wait a minute, I can hear you say, if Nature provides us the ultimate goals of survival and reproduction, isn’t this a problem not just for hedonists, but also for virtue-oriented schools like Stoicism? I’m glad you asked. I don’t think it’s as much of a problem for two related reasons: first, to live “according to Nature” for the Stoics means to use reason and behave prosocially. Arguably those are precisely the two major weapons evolution has given us in order to survive and reproduce. Second, the Stoics define virtue as rational pro-social behavior, so it turns out that to live according to Nature is to live virtuously. QED.

I see the relationship between evolutionary biology and the wisdom traditions differently.

You note that “it is clear what the only ultimate goods that nature set for us (and for all living organisms) are: survival and reproduction.”

The waters frequently get muddy when we talk about goods on the one hand, and means and ends on the other. So let’s say this - the ultimate end that nature set for all living organisms is reproduction. Period. Reproduction requires sex (a means). Sex requires courtship (a means). Courtship requires survival (a means). Survival requires food and some modicum of shelter. And so on.

Viewed this way, there is not much of a relationship between evolutionary biology and the wisdom traditions. Live long enough to have sex and reproduce. That’s about it. Don’t need Stoicism or Epicureanism - or Taoism, or any of the rest - for that.

Instead, I think the better approach is to view it this way: somehow, through culture and consciousness and a stable and cooperative natural platform, Homo Sapiens has evolved to a state where it exists and occupies a space well beyond the limited groove of our basic biological imperative.

We’ve elected to use this opportunity to expand what it means to “live” beyond mere reproduction. The wisdom traditions have developed over time - within the context of said culture and consciousness and natural platform - to help us define what this can mean, how to fill this space.

Evolutionary biology is useful in this exercise, because it can give us insights into the natural and ancient wiring which remains part of our biological inheritance. The study of emotions is one such example. When we understand what they are biologically, and how they operate physiologically, we have a better and deeper foundational context upon which to advance the development of the wisdom traditions.

In other words, we want to do more than merely reproduce. We want to “live.” What that means is an eternal process of cultural experimentation and individual exploration. The wisdom traditions help - enormously. And the wisdom traditions themselves are helped - enormously - when instead of simply occupying or being derived from a place of “pure reason” (whatever or wherever that is), they are situated and informed within the realm of active, real and embodied Homo Sapiens, and the messy and complicated biological systems of which we are comprised.

Also, I don’t like it when you set up these “competitions” and give Stoicism the benefit of the doubt and all your personal modifications thereof (your Stoicism is most certainly not the Stoicism of the ancients, which is fine so far as that goes) but characterize the position of your “opponents” in flatter and more strawman-like ways, anchored in a pre-history from which you allow yourself some escape. But I digress and this comment is already way too long :)

Thanks as always for the thought-provoking articles. I am fairly certain that I read every (non-ivory tower) thing you publish, and I am better for it, and appreciative!

Hm, "good pain" "bad pain", this reminds me of the hedonic calculus from Epicureanism. They would bring the argument to choose pain for a greater pleasure or avoiding greater pain. But ok what is with having pleasure about pain like mentioned in the text ?

And is virtue not also instrumental to surviving and reproduction ?

Ok, when with self-preservation the character / virtue as such is meant maybe.

But the goal of Epicreanism is not "life" or "self-preservation" but the happy life (their eudaimonia).

Their action can even go against life (suicide to avoid life-long great pain for example).

So for tranquility (pleasure) it is important to act according to the own values.

But what about values ? What is the interrelation between values and pleasure/pain ?

Aren´t pleasure/pain feedback from nature or the own value system ? The feedback from the desire for self-preservation and reproduction ?

For Stoics, values come from value judgment or ? So from value of indifferents and virtue.

Is in rational judgments no feeling involved ? (Dopamine, Serotonine...) what would the neurologists say ?

I know the Stoic idea of eudaimonia/happy life is to do the right thing which includes reducing suffering / pain and bring pleasure for oneself and others but with being indifferent to the feedback or receiving the results (that is in the hand of fate).

Epicurus hedonic calculus:

"...129] And for this cause we call pleasure the beginning and end of the blessed life. For we recognize pleasure as the first good innate in us, and from pleasure we begin every act of choice and avoidance, and to pleasure we return again, using the feeling as the standard by which we judge every good.

And since pleasure is the first good and natural to us, for this very reason we do not choose every pleasure, but sometimes we pass over many pleasures, when greater discomfort accrues to us as the result of them: and similarly we think many pains better than pleasures, since a greater pleasure comes to us when we have endured pains for a long time. Every pleasure then because of its natural kinship to us is good, yet not every pleasure is to be chosen: even as every pain also is an evil, yet not all are always of a nature to be avoided."

https://www.epicureanfriends.com/wcf/lexicon/index.php?entry/83-epicurus-letter-to-menoeceus/