[Based on How to be Queer: An Ancient Guide to Sexuality, by Sappho, Plato, and other lovers, translated by Sarah Nooter. Full book series here.]

What is the difference between love and lust? Does the former require the latter? Is the latter inevitably a conduit to the former? From a biological perspective, lust for sex has been ingrained into us by natural selection because otherwise we would likely not bother having sex, which is necessary for the propagation of our genetic lineage.

I mean, think about it: courtship requires time and resources, and it exposes you to attack from predators—at least if you were living in the African savannah. If it weren’t pleasurable, you’d rather take a nap. Or have a snack. But of course nature is not destiny. As evolutionary psychologist Steven Pinker once put it, he decided to spend his life pursuing his career and cultivating friendships rather than having children. And if his genes didn’t like it they could go on and jump into a lake.

The anthropologist Helen Fisher examined research on the issue of the relationship between love and lust and concluded that there is evidence for three phases of love in the human primate: (i) the lust phase, when we are moved by an intense sexual desire for the other person; (ii) the romantic phase, when we conceptualize (and, mostly, rationalize) our love interest as being the best person ever, the perfect soul mate, and so on; and (iii) the attachment phase, during which both lust and romance give way to a deeper, but calmer feeling of contentment with the relationship and acceptance of the other person’s inevitable quirks or shortcomings. Each phase is even accompanied by its own specific hormone profile: testosterone (in men) and estrogen (in women) for lust; norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin for romance; and oxytocin and vasopressin for attachment.

But of course we all know, or have experienced, exceptions to the three-phase rule. Sometimes lust doesn’t evolve into romance, or romance doesn’t yield to attachment. Sometimes one or two phases can be skipped altogether.

Shifting to a more conceptual level for a moment, my keyboard’s dictionary defines lust as “a passionate desire for something” and in the specific case of sex, as “a very strong sexual desire.” Romance is defined as “a feeling of excitement and mystery associated with love,” and the latter is characterized as “an intense feeling of deep affection.” That sounds about right, at least as a first approximation, so we’ll go with these definitions for the purposes of the current essay.

In modern culture, romance and love have positive connotations, while lust has a bit more dubious status. Most of us want to feel lust for something or someone, because it’s a good feeling. But the term also evokes a tendency to behave irrationally in the pursuit of one’s object of lust, even to highly detrimental effects for ourselves or others. Think of the stereotypical married man who cannot control his lust for a woman who is married to a friend, gives in to his impulses (and she to hers), in the process ruining two marriages and a friendship.

The ancient Stoics, had they read Fisher’s book, would have likely come up with a different classification, putting both lust and romance into the “passions” (pathe), or unhealthy emotions, and separating out love (of the appropriate kind) as a healthy emotion (eupatheia). The unhealthy emotions, in Stoicism, are defined as those that have a tendency to override reason, or that push us to do things that are against reason. Again, think of the philandering man just described. The healthy emotions, by contrast, are those that are guided by, or align with, reason. Love for one’s partner, or children, or friends, falls into this second category.

I was reminded of all of the above while reading “How to be Queer: An Ancient Guide to Sexuality, by Sappho, Plato, and other lovers,” a collection of translations by Sarah Nooter for the ongoing Ancient Wisdom for Modern Readers series being published by Princeton University Press. Usually, when I write about this series, I provide an overview of the whole book, but in this case I will focus only on the last two chapters, because in my mind they encapsulate most of what’s going on with sex, lust, romance, and love.

This is not at all to say that the first nine chapters of the book aren’t well worth reading. They present us with a superb sampler of poetry and prose, including Homer writing about the passion of “swift-footed” Achilles, Pindar on Poseidon and Pelops, Sappho on lesbian love, Aristophanes and Euripides on gender bending, and of course Plato on the origin of love (in the Symposium). All of it highly enjoyable and well worth reflecting on.

But the last two chapters are simply superb. The first one (chapter 11 in the collection curated by Nooter), is comprised of two contrasting arguments put forth by Socrates in Plato’s Phaedrus; the second one (chapter 12) is the famous speech given by Alcibiades in Plato’s Symposium, this one addressing Socrates. They are masterpieces of philosophy, rhetoric, and literature.

Let us begin with the two arguments articulated by Socrates to Phaedrus. They both concern the madness and passion of love. The first argument is meant to discourage a young man from entering into a relationship with an older man who is in love with him, advising the youth instead to prefer a man who is not in love. The second argument does exactly the opposite, and Socrates explicitly tells Phaedrus that the first argument is wrong while the second one hits the mark. Let’s see if you agree.

Socrates begins by setting up the scene and the goal of the first argument:

“There was once a boy, or rather a youth, and he was very handsome. He had a great many admirers. There was a wily one among them who was no less in love than the others but persuaded the boy that he was not. And at some point, while wooing him, he convinced him of this too, that it was right to please someone who is not in love with him rather than someone who is.”

Is this right, that it is better to yield to someone who is not in love with us? Before we can answer the question directly, says Socrates, we need to examine the very concept of eros. (Keep in mind here that although obviously the Greek word is the root of our term “erotic,” the original meaning was much broader). Eros, it turns out, is desire. And inborn desire for pleasure is one of the forces that control a human life, the other being the cultural influences to which we are all exposed, and which nudge us to seek what is best according to the culture in which we grow up.

Socrates here suggests that when cultural influences prevail and lead us toward what is best by way of sound reasoning we call that “moderation.” However, when desire rules we seek pleasure for its own sake and we are brought to “excess.” For instance, we need food to stay alive, but when desire for food overrides moderation then we become gluttons, and gluttony is a vice. Similarly:

“Desire that overpowers the influence of reason to do what’s right and that leads to the pleasure of the beautiful and that, again, is vigorously strong-armed by similar desires toward the beauty of the body, and that wins out in the end—this desire takes its name from this very force and is called eros.”

You can see where this is going: to grant our favors to someone who is in love with us, and who is therefore ruled by eros, is problematic, because it will lead to excess, not moderation. This is the root of all sorts of ancillary vices, including jealousy and possessiveness. A relationship controlled by eros will be destructive to one’s family, friendships, and material possessions, all of which will be sacrificed to the altar of lust and the madness of eros. In conclusion, says Socrates:

“My boy, you must keep these things in mind and know that the affection of a lover is not derived from goodwill but rather is like a desire for food for the sake of satisfaction. Just as wolves love lambs, so do lovers adore their lad.”

At this point, however, the sage of Athens completely switches sides, telling Phaedrus:

“Know this then, handsome lad, that the prior speech … is not true. … For if it were simply the case that madness is bad, then [the speech] would be well spoken. But the fact is that the greatest of benefits comes to us through madness, or at least the kind given by divine grace. For indeed the prophetess at Delphi … when maddened has conferred the greatest goods upon Greece in private and public matters.”

You see, we all agree that eros and the lust for the lover that it generates is madness, the antithesis of reason. And yet we also know that certain kinds of madness are the most divine thing a human being can possibly experience. This, continues Socrates, will not be believed by those who are merely clever, but will be accepted as true by those who are actually wise.

Eros, Socrates states, is nourishment for the soul, which would otherwise dry up. Desire has the power to freshen and warm the soul, which is why we feel joy when in the presence of the beloved. The soul cannot stand to be without the lover, and that is why it forgets mothers and fathers, brothers and friends, as well as “all the rules of decency.” Socrates gets downright poetic in his enthusiastic defense of eros:

“The flowing water of that rushing river—which Zeus when in love with Ganymede called the ‘rush’ of desire—washes over the lover, and some of it settles within him, while some of it overflows and streams forth into the world.”

When I finished reading Socrates’s two speeches my first thought was that the Stoics had a point: the second situation described in the Phaedrus, the state of the soul of the lover, sounds ghastly, truly a kind of madness. Perhaps it comes from the gods or, as we would say today, from evolution, but either way it easily wrecks things, taking control of us and leading us to excesses that we will surely regret once the rush has passed. And you can count on the fact that it will pass.

Or maybe you disagree and find the whole notion of a temperate love to be insipid and unattractive. Either way, one thing is startling here: where is the Socrates who has become a legendary embodiment of reason and temperance? You know, the guy who argues amiably with friends and strangers alike, who is steadfast in the midst of battle, and who serenely faces death by hemlock?

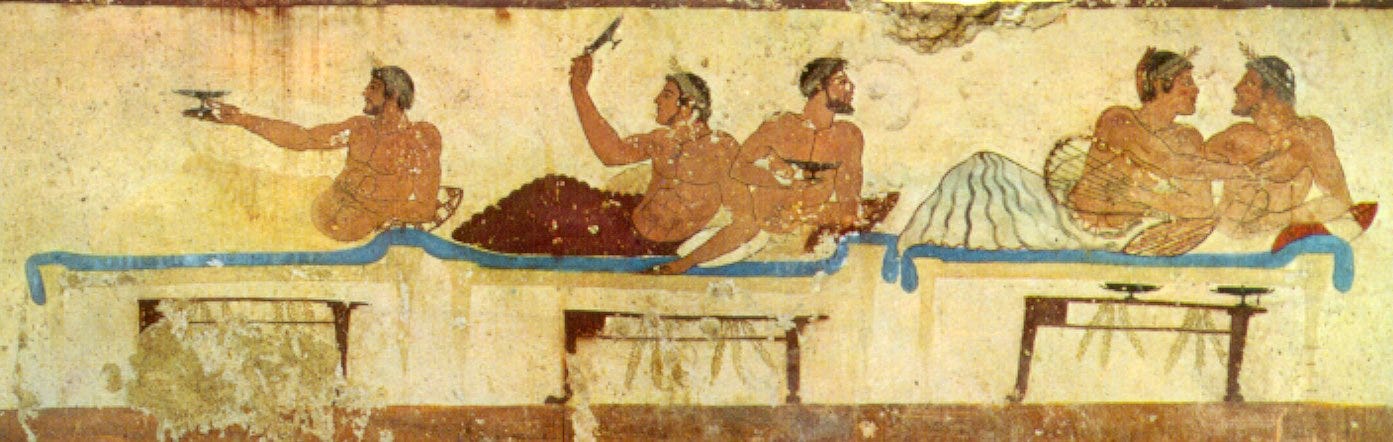

We find that Socrates in the following, and last, chapter of Nooter’s book, the one devoted to Alcibiades’s speech in the Symposium. The scene is the house of Agathon, a poet who has invited a number of friends over for a drinking party in order to celebrate the triumph of his first tragedy. Each guest, including Aristophanes and Socrates, gives a speech in honor of love. Near the end, the legendary Alcibiades crashes the party and delivers his own speech, which is a forlorn love letter to none other than Socrates.

Alcibiades was impossibly handsome, incredibly wealthy, witty, brave, and devilishly cunning. He had a very high opinion of himself, and was usually able to easily convince others to do his bidding. He will eventually play a major role in the Peloponnesian War, which will end in a disaster for Athens. He will also be hunted down and killed by Spartan spies, not before he rushed naked at them while brandishing his sword and shield, instilling so much fear in his opponents that they contended themselves to shoot him down at a distance, by using arrows and spears. [1]

At Agathon’s symposium, however, Alcibiades is a much diminished man, and the fault is Socrates’s. Alcibiades begins his speech by announcing that he will reveal the real Socrates to those present. He says that Socrates pretends to be ignorant of all things, but in reality always knows exactly what he’s talking about. Moreover, he is endowed with a near infinite reservoir of temperance.

Proof of this is that Alcibiades, madly in love with the philosopher, has tried multiple times to seduce him. He made an attempt once that they were alone at the gym. Nothing. He made another attempt at his house, but Socrates walked out immediately after dinner. Finally, he got Socrates to spend the night, and here is what happened (or didn’t happen, depending on how you look at it):

“I wrapped my coat around him—for it was winter—and lay beneath his own thin cloak, like so, putting my arms around this truly devilish and wondrous man. I lay there all night. And in these things, again, Socrates, you cannot say that I am lying! For when I had indeed done all that, this man showed himself to be utterly superior and to hold my youth in contempt, mockery, and insult—and in regard to the very thing in which I thought I was really something, o gentlemen of the jury. For you are the judges of Socrates’s arrogance! Know well by the gods and goddesses, that when I arose in the morning I had no more had relations with Socrates than I would have had I slept with my own father or older brother.”

Alcibiades was made mad by eros, but of the lowest kind, the sort that we associate with sexual lust. Socrates by contrast, is in love with wisdom—the literal meaning of a philosopher—and while he does not disdain earthly pleasures, he is always in control of himself, exercising temperance, which is the control of desire by reason. What a contrast with the Socrates of the Phaedrus!

I leave it to you to ponder which version of Socrates you prefer, or to consider whether the Stoics were right in cautioning us not to yield to the pathe and to instead mindfully cultivate the eupatheiai. As to why Plato presents us with such contrasting portraits of Socrates, we need to remember that his dialogues were meant primarily as a teaching tool for his students at the Academy [2]. As any good teacher knows, you don’t present your pupils with the truth ready made. You stimulate their curiosity so that they work it out for themselves.

_____

[1] For more about the complex relationship between Socrates and Alcibiades see The Quest for Character: What the Story of Socrates and Alcibiades Teaches Us about Our Search for Good Leaders, Basic Books, 2022.

[2] Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy, by Robin Waterfield, Oxford University Press, 2023. See my conversation with Robin here.

[Previous installments: I, II, III, IV, V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII, XIV, XV, XVI, XVII, XVIII, XIX, XX, XXI, XXII, XXIII, XXIV, XXV, XXVI, XXVII, XXVIII, XXIX.]