In defense of Seneca

We need to cut some slack to the most controversial of the ancient Stoics

I spend a significant amount of time discussing all aspects of Stoicism both on and offline. One of the topics that never fails to come up is whether one should really read Seneca, considering his, shall we say mixed reputation as a politician and businessman. Seneca was indubitably sexist, unarguably ultimately failed to rein in Nero, and possibly (though not likely) triggered the bloody Boudica rebellion by suddenly calling in a vast amount of loans he had made to the Britannic aristocracy. How does that square with being a Stoic, let alone with someone at least aspiring to be a Sage?

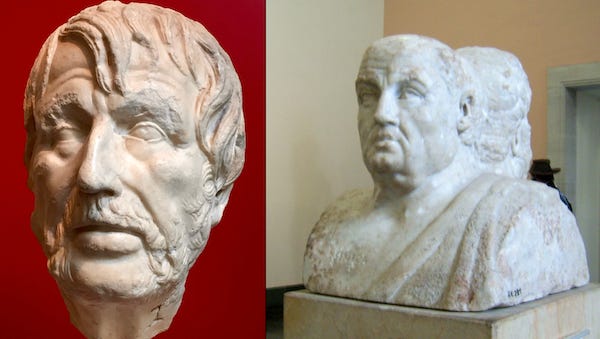

Even what Seneca looked like has been a matter of dispute. For centuries he was portrayed as the sort of emaciated man in the left side of the image below. But in fact, we now know that he looked rather plump, as in the right side of the same image. The version on the left, known as Pseudo-Seneca, is suspected to actually represent either the playwright Aristophanes or the poet Hesiod, but it was more appealing as Seneca because it simply fit much better with the idea of the philosopher-sage lost in thought and unconcerned with worldly goods. By contrast, the Pergamon Museum version on the right smacks of a well fed patrician who may have been talking the talk but not walking the walk.

Seneca’s figure is so fascinating that two modern biographies of him have been published, both well worth reading: The Greatest Empire, by Emily Wilson, and Dying Every Day, by James Romm. And that’s without counting the 1920 classic The Stoic, by Francis Caldwell Holland, or the (apparently awful) recent movie with John Malkovich. Clearly, there is a wealth of material to dig into for people interested in Seneca the historical figure. And you can read all of his works (plays, letters of consolation, philosophical essays, and letters to his friend Lucilius) for just $2.99. (If you prefer more modern translations, they are worth the higher price.)

The question that I wish to address here is whether a modern Stoic should read Seneca for insight and inspiration, the way nobody questions both Epictetus and Marcus Aurelius should be. Or whether, on the contrary, he should be expelled from the canon on account of the alleged massive inconsistency between his principles and the way he lived his life. Epictetus himself, after all, reminds us that Stoicism is about practice, not just theory:

“If you didn’t learn these things in order to demonstrate them in practice, what did you learn them for?” (Discourses I, 29.35).

So let us focus on that subset of the bare facts that is of direct relevance to our project. To begin with, it is the case that Seneca was very wealthy, indeed one of the wealthiest and most influential men in Rome. That in and of itself, however, does not constitute a contradiction with Stoic philosophy. It is true that Epictetus’s version of Stoicism leaned toward the rather minimalist and anti-materialist approach of the Cynics, but wealth does fall squarely under the “preferred indifferents,” i.e., the sort of externals that it is okay to pursue so long as they don’t get in the way of the only thing that truly matters for a Stoic, the practice of virtue.

Then again, Seneca repeatedly warns about the many temptations induced by wealth, almost as a reminder to himself:

“He who craves riches feels fear on their account. No man, however, enjoys a blessing that brings anxiety; he is always trying to add a little more. While he puzzles over increasing his wealth, he forgets how to use it. He collects his accounts, he wears out the pavement in the forum, he turns over his ledger—in short, he ceases to be master and becomes a steward.” (Letter XIII.17)

Let us not forget, of course, that Seneca had lost a great deal when he was exiled in 41 CE by the Senate, on likely trumped up charges of committing adultery with Julia Livilla, the sister of former emperor Caligula. The new emperor, Claudius (whose own record was rather mixed), commuted the original death penalty into exile, and the historian Cassius Dio suggests that Seneca was a victim of an attempt by Messalina, Claudius’s wife, to get rid of Julia. Seneca remained in exile on the island of Corsica (at the time not at all the resort destination that it is today) for eight years.

After Claudius’ death Seneca penned the hilarious essay known as On the Pumpkinification of the Divine Claudius, a rare example of Menippean satire. In it he mocks Claudius and, more broadly, takes aim at the whole Roman custom of making emperors into gods. According to Allan Presley Ball, who translated the Pumpkinification essay: “Seneca appears to have been concerned with what he saw as an overuse of apotheosis writing as a political tool. If an Emperor as flawed as Claudius could receive such treatment, he argued elsewhere, then people would cease to believe in the gods at all.”

The satirical piece has also often been interpreted as an attempt at flattering the new kid on the block, Nero, whose mother, Agrippina, had managed to recall Seneca from exile. That would definitely not be the behavior of a good Stoic. But historians have pointed out that Seneca’s optimism over the young princeps was actually shared throughout Rome, as it really seemed, for a while, that the awful times of Caligula and the highly questionable ones of Claudius might finally be over.

Seneca then wrote another essay dedicated to Nero: On Clemency. This too is often interpreted by critics as an example of the philosopher’s ingratiating approach toward the emperor. But these people must have read a different version of On Clemency than I did. There are several passages in the book where Seneca not so subtly threatens Nero, reminding him on the basis of ample historical precedent that he better act virtuously and in the interest of the people, or else. Consider, just as one example among many, the following excerpt:

“A cruel reign is disordered and hidden in darkness, and while all shake with terror at the sudden explosions, not even he who caused all this disturbance escapes unharmed. … The safety of kings on the other hand is more surely founded on kindness, because frequent punishment may crush the hatred of a few, but excites that of all.” (I.7-8)

I don’t know about you, but it seems to me that it takes some guts to write this to someone who could have you sent into exile or executed at the snap of a finger.

What about the above mentioned calling in of loans that allegedly caused the rebellion in the British provinces? It is actually far from clear whether Seneca’s actions were a contributing factor at all, and even more doubtful that he was aware of the risk when he made the decision on financial grounds.

Also, in terms of his wealth, Seneca did try to use it as a way to buy himself retirement (and dedicate his time to philosophy) once things began to go south with Nero, an attempt that succeeded only partially (he got to spend more time in one of his country estates), and only temporarily.

Seneca’s use of wealth may have been most important—and also most difficult to disentangle from his political intentions and actions—during the first five years of Nero’s reign. In that period the philosopher advised the young emperor in cooperation with the Praetorian Prefect, Sextus Afrianus Burrus. Those years are referred to by historians as the quinquennium Neronis, and are generally regarded as actually having been prosperous for Rome, so it is legitimate to infer that Seneca and Burrus did a good job under very precarious and difficult circumstances.

Nero, however, became more and more paranoid (or not: there actually were real plots against his life), and eventually murdered his own mother, Agrippina in 59 CE (to be fair, she was, in fact, plotting against him at the time). It is doubtful that either Seneca or Burrus had anything to do with it, since their influence on Nero was by then on the wane.

It is, however, definitely the case that Seneca wrote a speech for the Senate essentially excusing the murder. While this is obviously not in line with Stoic principles, it is hard to know exactly what was going on in Seneca’s mind. He may, for instance, have calculated that by way of this move he was going to be able to rein in Nero some more, thus saving Rome from another bloody civil war. If that was his plan, it failed.

Three years later Burrus died, which further escalated the situation, leading to the unsuccessful Pisonian conspiracy against Nero in 65 CE and consequently to Seneca’s own commanded suicide. Seneca was probably not involved directly in the conspiracy (unlike his nephew, the poet Lucan, who was also sentenced to death), but he almost certainly knew about it. And knowing of a conspiracy against the emperor without alerting the authorities is as good as being part of the conspiracy. Regardless, and whatever his political mistakes, Seneca paid for them with his life.

Regarding his death, people sometimes comment that he staged things in order to appear as a Roman Socrates, though the proceedings didn’t go smoothly and it took several attempts to finally achieve the objective. Such accusation seems more than a bit uncharitable: surely Seneca did have Socrates, a role model for Stoics, in mind; and, likely, he was trying to do the best while performing the last act of his life. But he was going to die unjustly nonetheless, so cut the guy some slack.

When considering Seneca’s overall political influence and behavior with Nero, we need to remember a number of things. First, that we only have a handful of accounts of what happened, mostly from people who clearly and openly disliked Seneca. Second, that to control a sociopathic tyrant is a task not many would even attempt, let alone succeed at for five full years. And lastly, consider Thomas Nagel’s concept of “moral luck“: if we feel so smugly superior to Seneca (or anyone else who acted badly under extreme circumstances), that’s just because we got lucky enough not to be seriously morally tested ourselves.

What about Seneca’s sexism? There is no question at all that the charge sticks, to a point. This modern reader cringes every time that Seneca refers to an unbecoming or unvirtuous behavior as “womanly,” for instance when he writes:

“Anger, therefore, is a vice which for the most part affects women and children. ‘Yet it affects men also.’ Because many men, too, have womanish or childish intellects.” (On Anger, I.20)

Aarrgghh! Then again, at other times he did rise above such talk, sounding surprisingly modern:

“I know what you will say, ‘You quote men as examples: you forget that it is a woman that you are trying to console.’ Yet who would say that nature has dealt grudgingly with the minds of women, and stunted their virtues? Believe me, they have the same intellectual power as men, and the same capacity for honorable and generous action.” (To Marcia on Consolation, XV)

Seneca’s reputation has always experienced rather dramatic ups and downs, from his own time until now. The Roman historian Tacitus claims in The Annals that accusations against Seneca did not hold up to scrutiny and were likely the result of envy or political antagonism. The early Christian Fathers thought highly of Seneca, with Tertullian referring to him as “our Seneca.” Dante, in the Divine Comedy, puts him in Limbo, that is not quite into the depths of Hell, a high honor for a pagan. (Though the Italian poet gives an even higher honor to another Stoic, Cato the Younger, whom he places at the entrance of Purgatory: “What man on earth was more worthy to signify God than Cato? Surely none.”) Several Renaissance authors celebrated Seneca the writer and philosopher, including Chaucer, Petrarch, Erasmus, John of Salisbury, and Montaigne.

In modern times, the scholar Anna Lydia Motto challenged the common negative portrait of Seneca, which she points out is based almost entirely on the account of Publius Suillius Rufus, a senatorial lieutenant under Claudius:

“We are therefore left with no contemporary record of Seneca’s life, save for the desperate opinion of Publius Suillius. Think of the barren image we should have of Socrates, had the works of Plato and Xenophon not come down to us and were we wholly dependent upon Aristophanes’ description of this Athenian philosopher. To be sure, we should have a highly distorted, misconstrued view. Such is the view left to us of Seneca, if we were to rely upon Suillius alone.” (Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic, The Classic Journal 61:257, 1966)

Philosopher Martha Nussbaum maintains that Seneca’s intellectual contributions are significantly more original than previously thought, on topics ranging from the role played by emotions in our lives (The Therapy of Desire, Princeton University Press, 1996) to political philosophy, to his concept of cosmopolitanism (Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education, Harvard University Press, 1999).

Another contemporary scholar, Robert Wagoner, wrote this about the complex question of the relationship between Seneca’s life and his philosophy:

“A number of views can be taken here. Perhaps Seneca simply fails to live the philosophical life he aspires to live. Perhaps his philosophical ambitions were really secondary to his political ambitions. While many scholars have noted the inconsistencies and many have rejected Seneca’s work on the grounds of hypocrisy, some scholars (notably Emily Wilson) have challenged this view. Wilson notes that, ‘The most interesting question is not why Seneca failed to practice what he preached, but why he preached what he did, so adamantly and so effectively, given the life he found himself leading.’” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Let me conclude by giving the last word to the man himself, who very clearly not only denied that he was wise, but also told his friend Lucilius that it was not a good idea to seek advice from him:

“What, then, am I myself doing with my leisure? I am trying to cure my own sores. If I were to show you a swollen foot, or an inflamed hand, or some shriveled sinews in a withered leg, you would permit me to lie quiet in one place and to apply lotions to the diseased member. But my trouble is greater than any of these, and I cannot show it to you. The abscess, or ulcer, is deep within my breast. Pray, pray, do not commend me, do not say: ‘What a great man! He has learned to despise all things; condemning the madnesses of man’s life, he has made his escape!’ I have condemned nothing except myself. There is no reason why you should desire to come to me for the sake of making progress. You are mistaken if you think that you will get any assistance from this quarter; it is not a physician that dwells here, but a sick man. I would rather have you say, on leaving my presence: ‘I used to think him a happy man and a learned one, and I had pricked up my ears to hear him; but I have been defrauded. I have seen nothing, heard nothing which I craved and which I came back to hear.’ If you feel thus, and speak thus, some progress has been made. I prefer you to pardon rather than envy my retirement.” (Letters to Lucilius, CXVIII, 8-9)

Was not aware of Senecas negative reputation. I’ve read/re-read him many times, for many years; he’s actually my favorite Stoic ‘read’. I’d shutter to think ( not really 😝; that’s out of my control ) what impression people who don’t know me would think if they were reading what “enemies’ wrote of me…

My personal opinion is that accusations of sexism against Seneca are overblown. He was a man of his times and no doubt took as a given the gender roles assigned by his society. Heaven knows, women of his day, given their straitened circumstances, had plenty to be angry about, so perhaps his "accusation" was merely an observation.

I dare say the time may come, probably when all of our bones have long since turned to dust, when the anti-male sentiments of today's mainstream (not to mention "radical") feminists will be branded as personal failings.