Let’s talk about (biological) sex—part I

From a Vegas conference to a scientific puzzle: why sex isn’t going away

I can’t believe I’m about to go there. For quite some time now I have made it my policy to stay away from current political and partisan controversies, on the ground that half the audience won’t even listen and the other half already agrees anyway. Not much to gain, possibly a lot to lose. Instead, as my readers might have noticed, I write about ancient history and philosophy, focus on episodes or concepts that are of value today, step back, and let people draw their own parallels and conclusions.

But occasionally one needs to make exceptions to rules, and this is one. We are going to talk about (biological) sex, baby! (But not gender. And not gender roles. Or sexual preferences. Just sex.)

I can’t believe I feel compelled to start with a disclaimer, but here it is: nothing that you are about to read should be construed as somehow opposing the rights of transgender people. If that’s going to be your conclusion, I don’t know what to tell you, other than you are flat out wrong.

The story begins back in October of last year, when I was invited to give the opening keynote at the annual CSICon, the major conference of scientific skeptics, held in Las Vegas and organized by CSI, the Center for Skeptical Inquiry. (They publish Skeptical Inquirer magazine, for which I write. The former editor was a friend and esteemed colleague.) The title of my talk was “Why bother? The nature of pseudoscience, how to fight it, and why it matters.” I’ll publish an article based on it soon.

Shortly after me, my friend Steven Novella, of Skeptics’ Guide to the Universe fame and a neurologist by profession, got on the stage and delivered his talk, entitled “When skeptics disagree.” I found myself nodding along, except when Steven got to the “controversy” about biological sex. He said that biologists themselves disagree on the best definition of sex: does it have to do with chromosomes? Is it about anatomy? Behavior?

I immediately thought, uh-oh, here comes trouble! You see, I knew that one of the speakers slated for later on in the conference was my colleague Jerry Coyne, an evolutionary biologist and author of Why Evolution Is True. I expected Jerry to seriously disagree with Steven’s characterization of the “controversy.” And sure enough, he did.

Now, Jerry and I have at times not seen eye-to-eye about some matters, from technical issues concerning the nature of evolutionary theory to the roles of science and philosophy with respect to each other. But I thought in this case Jerry was right on target. Still, I let the matter go because of the policy explained above, and because CSICon is a friendly gathering where I’d rather have a nice conversation with fellow skeptics over martinis than fight yet another useless round of the culture wars.

Skip a few months ahead and a colleague of mine, a philosopher, sends me a paper just published in the prestigious journal Biology & Philosophy. The authors are Aja Watkins, of the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Marina DiMarco, of Washington University in St. Louis. The title of their paper is “Sex eliminativism.” It is a highly technical, clearly written and very well argued paper. But it also is, I think, fundamentally flawed, and a good example of why some scientists really dislike philosophers.

I’m going to take my time going through Watkins & DiMarco’s paper, trying my best to explain what they are saying and why, as well as why I believe they got things wrong. That’s why, unusually, this is a two-part essay. Broadly speaking, I suspect Steven would agree with the paper, while I know for a fact that Jerry doesn’t.

The authors begin with the following: “This paper first argues that realist accounts of sex are wanting. We present a positive argument in favor of anti-realism about biological sex, and argue that, in practice, eliminating biological sex from large swaths of biological theory and practice is preferable.” (p. 2)

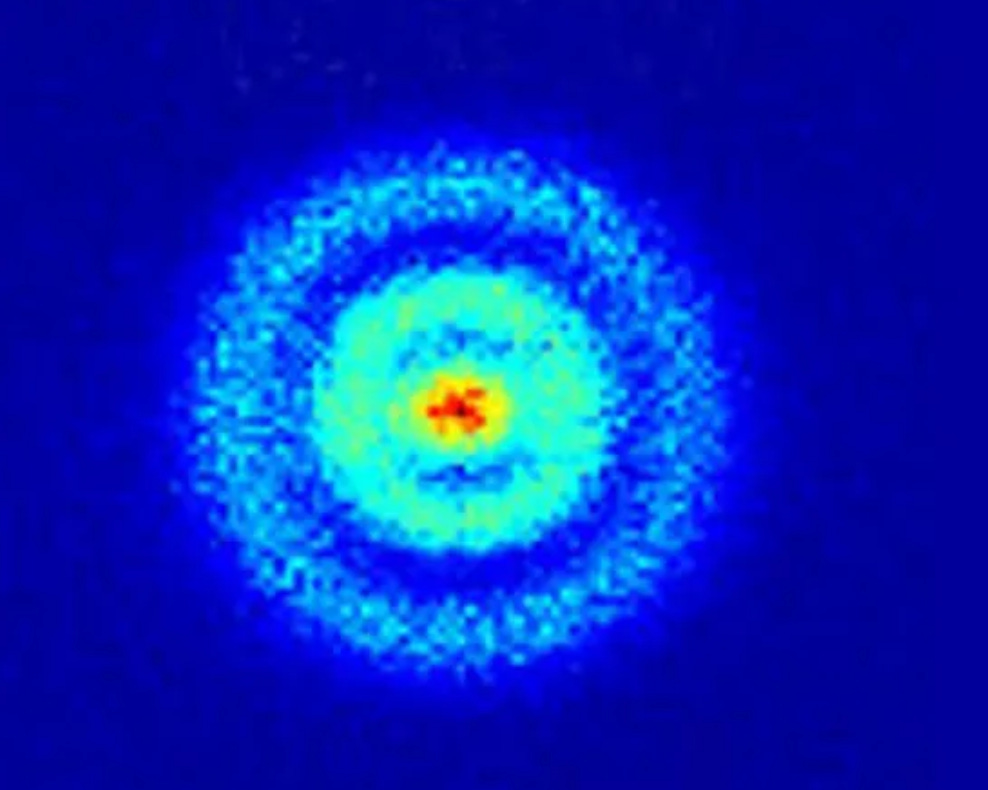

Okay, before we can proceed we need to get clear on what the three crucial terms invoked by Watkins & DiMarco actually mean. Realism, anti-realism, and eliminativism are three metaphysical positions about scientific theories or concepts. Let’s consider a concrete example to make the distinctions among the three as clear as possible. We have all heard about atoms, right? They are the basic units of a chemical element. There are atoms of hydrogen, of oxygen, of gold, and so forth. Their internal structure is different, and indeed it is precisely such differences that confer distinguishing properties to the various elements. Hydrogen consists of a single proton (a positively charged particle) and a single electron (a negatively charged particle). Oxygen’s nucleus contains 8 protons and 8 neutrons (electrically neutral particles) and is surrounded by 8 electrons. Finally, gold is made of a whopping 79 protons, 118 neutrons, and 79 surrounding electrons.

Now, if you are a realist about atoms, neutrons, protons, and electrons, you will say that what I just gave you is a description of how things actually are, to the best of our knowledge. That is, there really are out there things like atoms, and they really are made of things like neutrons, protons, and electrons.

But if you are an anti-realist about atoms and their constituents, you will say instead that these are convenient conceptual or mathematical entities that are invoked by scientists in order to account for observable phenomena. After all, the particles themselves are not, in fact, observable (unless you happen to have handy a special instrument called a scanning tunneling microscope) and their existence needs to be deduced or postulated.

What about eliminativism? This is a position that says that not only there is no good reason to assume that atoms and particles actually exist. They are not even needed as concepts because they don’t do any useful work within any scientific theory. They can, therefore, be eliminated (from scientific, and presumably also lay discourse).

Nobody that I know of is an eliminativist about atoms and subatomic particles, and most scientists, at this point, are realists about them. But this is a relatively recent consensus. Up until the beginning of the 20th century there was no agreement that atoms were real. It was Albert Einstein who provided the first evidence in favor of atomic realism by way of explaining Brownian motion (here is a fuller and better explanation). He published his analysis in one of the four landmark papers that characterized his famous “annus mirabilis” of 1905. (He later got the Nobel for another one of those papers, the one about the photoelectric effect.)

Is anyone an eliminativist about anything? Yes. I, for one, count myself as an eliminativist about the concept of race. It does not correspond to any biological reality, and it is socially pernicious. So I’d rather simply not use it. (I am definitely in a minority here.)

Another famous philosophical eliminativist is Patricia Churchland, who for decades now has pushed for the elimination of “folk” psychological concepts, such as pain, and their replacement with more accurate neurobiological descriptions, like “my C-fibers are firing.” Good luck with that.

Now that we are a little more clear about the distinctions among realism, anti-realism, and eliminativism, let us return to Watkins & DiMarco’s paper. They write:

“Most philosophers of biology, not to mention biologists themselves, are realists about biological sex. … The general consensus among biologists is that ‘males’ and ‘females’ are distinguished by the type of gamete members of each category produce. … The gametic definition generally does very well at applying to all forms of life that are ‘anisogamous,’ i.e., those organisms that produce gametes that are not all the same size. (Isogamous species produce only one size of gamete, but still reproduce sexually.)“ (p. 3)

Note that the above is a definition, not an empirical observation. Sexes are defined with respect to the size of gametes they produce. Definitions cannot be right or wrong, they can only be useful or not. There are, of course, empirical observations that stem from the definition of sex in evolutionary biology, specifically: (i) most species of multicellular organisms are anisogamous, and (ii) few of these have multiple sexes, i.e., produce a variety, sometimes a continuum, of gamete sizes. These observations are what biologists wish to account for, and they have accordingly produced a number of theories—based on the gametic view—about the evolution of sexual strategies in nature.

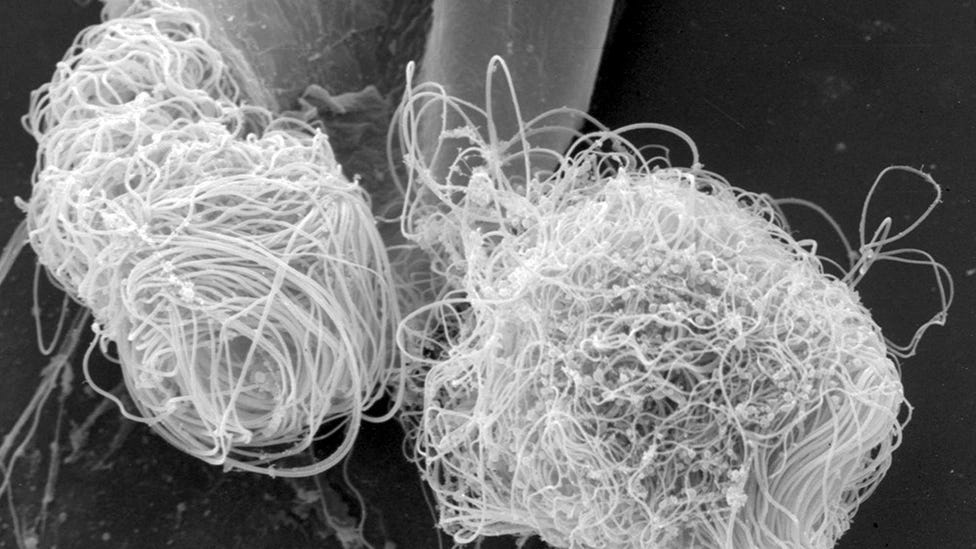

Okay, what’s the problem, then, especially given that—by admission of Watkins & DiMarco, most biologists and philosophers of science are in agreement? One problem is that: “The gametic definition is susceptible to counterexamples. For example, it is not guaranteed that all gametes with sperm-like morphology are necessarily smaller than all gametes with egg-like morphology; Drosophila bifurca, for instance, have gametes otherwise homologous to sperm but which range up to 5.8 cm in length.” (p. 4)

This is true, but possibly disingenuous, or at least misleading: while D. bifurca’s sperms are, indeed, very long compared to the eggs, most of the cellular material and sub-cellular organelles that get inherited by the offspring comes, as it is usual, from the eggs, not the sperms. Which means that functionally D. bifurca is not, in fact, an exception to the gametic rule. Also, biologists have a pretty good idea of why D. bifurca is so exceptional: the gigantic sperms likely evolved by what is known as a Fisherian runaway process.

At any rate, as the authors themselves acknowledge, biology is “messy” and the only rule is that there are always exceptions. But the rules often help explain the exceptions; failing that, the exceptions themselves point toward new, interesting discoveries. Watkins & DiMarco make an analogy with species concepts: there too, there are exceptions, and some species concepts apply only to certain groups of organisms and not others. But that’s interesting, rather than problematic, and biologists are not about to give up and become “eliminativists” about the notion of species (even though Watkins and DiMarco seem to think they should).

Still there is much more to the controversy, so please come back tomorrow for part II…

Thanks for the clarification!

Just wanted to point out that each gold atom has 79 (not 118) electrons...

Can't wait for the second part! As you know, I'm not here for Stoicism, but just renewed because this reminded me of the quality of the "Beyond" in your title.