Prosochē or not prosochē? On Stoic mindfulness

Is Stoic mindfulness a thing? If so, what is it?

“Mindfulness” has been all the rage for some time now. And it has, predictably, been criticized on both philosophical and effectiveness grounds. But I’m not concerned with either here. It’s pretty clear to me that while different philosophical traditions that use mindfulness (e.g., Buddhism) do make philosophically questionable assumptions, those assumptions are specific to each tradition, and need to be evaluated case by case. It’s also clear that although the benefits often claimed for mindfulness are likely exaggerated, the word refers to a panoply of mental techniques that are useful for modest but important purposes, such as calming oneself, paying more attention to one’s thought processes, and so forth. So, I’m going to take it as a given that mindfulness refers to a number of different techniques, that are more or less effective, and that are more or less based on certain specific philosophical and metaphysical assumptions.

What I wish to explore here, instead, is a debate within the Stoic community about our version of “mindfulness.” Specifically, whether it is, in fact, something that the ancient Stoics did, and whether it should be incorporated in modern Stoic practices. The answers, I think, are practically relevant to anyone who is either practicing Stoicism already or is curious about the impact that adopting this ethical philosophy might have on their own lives.

The debate I’m referring to concerns whether the Stoic concept of “prosochē,” usually translated as “attention” or “mindfulness” is: (a) a truly central concept in ancient Stoicism, and (b) best understood as anything like what we mean today by mindfulness. I don’t have a particular stake in this discussion, and I’ve changed my mind about it already a couple of times. Indeed, a major reason to write this essay is rather selfish: I want to clear my own fog about this topic, as I sense that it is important.

While different authors of course have slightly different takes on prosochē, the two basic positions can be summarized in this fashion:

(i) Prosochē is a central aspect of Epictetus’ philosophy, and it is useful to translate the term as “mindfulness.”

(ii) Prosochē is a minor aspect of Epictetus’ philosophy, and it is misguided to translate it as “mindfulness.”

Broadly speaking, on the side of (i) we have classic French scholar Pierre Hadot, “traditional” Stoic Chris Fisher, and author and cognitive behavioral therapist Don Robertson. On the side of (ii) we have my friend Greg Lopez, co-author with me of A Handbook for New Stoics: How to Thrive in a World Out of Your Control. If we were to go by majority opinion, or by weight of published scholarship—and with all due respect to Greg—(i) would win hands down. But this is philosophy, and appeals to popularity or to authority are both logical fallacies, so we are not going to fall for that.

Yes, prosochē is a form of mindfulness

Let’s start with the arguments put forth in defense of thesis (i). Fisher provides a good summary in his article, “Prosochē: Illuminating the Path of the Prokoptōn.” He begins by citing Epictetus:

“When you relax your attention for a while, do not fancy you will recover it whenever you please; but remember this, that because of your fault of today your affairs must necessarily be in a worse condition in future occasions.” (Discourses IV.12.1)

“Attention” in the quote above is rendered in the original Greek as prosochē. Epictetus mentions the concept in other places as well:

“Very little is needed for everything to be upset and ruined, only a slight lapse in reason. It’s much easier for a mariner to wreck his ship than it is for him to keep it sailing safely; all he has to do is head a little more upwind and disaster is instantaneous. In fact, he does not have to do anything: a momentary loss of attention will produce the same result.” (Discourses IV, 3.4–5)

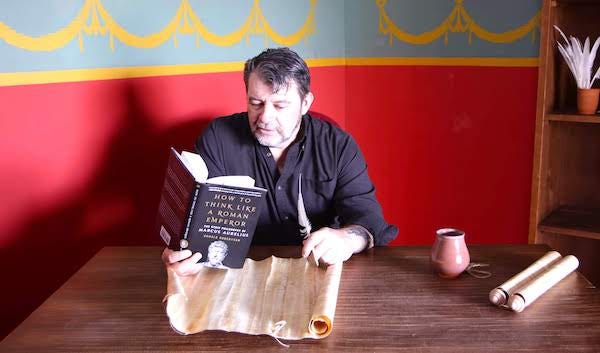

Prosochē, then, claims Fisher, is crucial for the practice of the three disciplines of Epictetus: desire and aversion (meant to train us to redirect our desires toward that which is under our control), action (to guide us when dealing with other people), and assent (to improve our judgments). Notice that Greg and I built our entire book around the three disciplines (and, for that matter, I organized my previous book, How to Be a Stoic, around them also). So we don’t disagree with Fisher that the three topoi, as they are often called, are crucial to the study and practice of Stoicism. Or at least, Epictetus’ innovative version of Stoicism.

Fisher in turn was inspired by classicist Pierre Hadot, arguably the man who put Stoicism back onto the modern map of philosophies of life, particularly with three books, Philosophy as a Way of Life, The Inner Citadel, and What is Ancient Philosophy? Here are a couple of choice quotes from Hadot, concerning prosochē:

“A fundamental attitude of continuous attention, which means constant tension and consciousness, as well as vigilance exercised at every moment.” (What is Ancient Philosophy?, p. 138)

And:

“Self-control… fundamentally being attentive to oneself… unrelaxing vigilance.” (Philosophy as a Way of Life, p. 59)

Fisher also mentions Don Robertson, who has written an essay in defense of position (i), and who in his The Philosophy of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy defines prosochē as:

“Attention to oneself which can also be translated as mindfulness or self-awareness.” (p. 152)

How does prosochē work, exactly? According to Fisher, by constantly reminding the agent to pay attention to the here and now (hic et nunc), and specifically to the following three things (Fisher, p. 3):

Present representations—proper discernment of the impressions which press themselves on our psyche.

Present impulses—the desires and aversions which define our moral will (prohairesis).

Present actions—the present acts inspired by one’s moral will.

But it is precisely at this point in Fisher’s essay (which is worth reading in its entirety) that trouble begins. He goes on to write (p. 3): “Vigilant focus on the present moment, often referred to as mindfulness, is most frequently associated with Buddhism in contemporary times. This is due primarily to the popularization of Eastern mindfulness practices in the West during later part of the twentieth century. However, as Donald Robertson suggests, the Buddhist concept of mindfulness ‘bears comparison to certain European philosophical concepts.’”

No, prosochē is not really a form of mindfulness

Enter my friend Greg, who is not just a practicing Stoic, but a practicing Buddhist as well. And he is familiar with both the Stoic and the Buddhist literature. He wrote an essay for Modern Stoicism entitled “Sati & Prosoche: Buddhist vs. Stoic ‘Mindfulness’ Compared,” where he defended thesis (ii).

Greg’s criticism of (i) is two-pronged: on the one hand, he claims that Stoic mindfulness, whatever it is, has little in common with Buddhist mindfulness (also, whatever it is, since there is quite a bit of disagreement on that too!). On the other hand, he suggests that the evidence in favor of a central role of prosochē in Epictetean philosophy, never mind in Stoicism in general, is pretty thin.

Let’s start with what mindfulness means, in and out of Buddhism. Greg points out that the currently popular conception of mindfulness comes “from Jon Kabat-Zinn, the researcher behind Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR). He defines mindfulness as ‘paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally.’”

Right off the bat, then, this is not what Stoics are supposed to do. Epictetus tells us very clearly that we should judge our impressions, analyze them in detail, and then decide whether to assent to them or not. So, while Stoic prosochē is about paying attention (indeed, Greg points out that it is most often translated as “attention,” not “mindfulness”), and it does lead us to act in the moment, it is most definitely not value neutral. Greg continues by explaining that Kabat-Zinn’s version of mindfulness may in turn have little to do with what early Buddhists practiced:

“In Pali [an ancient language derived from Sanskrit], the word we translate as ‘mindfulness’ is sati. … [Two similes from Buddhist tradition] seem to indicate that mindfulness can act as a kind of restraint on the mind and ‘streams in the world.’ Note that this is pretty different from ‘mindfulness’ as defined [by Kabat-Zinn]; there it seemed relatively passive. Here it’s not.”

More specifically, sati is a practice of watching four objects of attention as they arise and pass in your consciousness. These areas are: the body, feelings, the functioning of the mind, and the qualities of the mind. The goal is for the agent to remain focused on those four areas, while at the same time setting aside concerns about externals. Greg concludes:

“The above seems to indicate to me that sati has many of the same qualities of mind that a student has when studying a subject they’re engrossed in. This is indicated through the allusions to memory and knowledge mentioned several times. But instead of studying textbooks, the practitioner is studying their phenomenological experience. There is also a judgmental aspect of sati that is not present in Jon Kabat-Zinn’s definition of a more modern form of mindfulness. … One does not seem to simply observe passively, but instead one takes note of what phenomena are helpful or hurtful, how they are so, and what makes them arise and cease. In short, sati seems to be the careful self-study of one’s physical and mental experiences.”

Which, again, is not really what prosochē is. Yes, the Stoic practitioner is supposed to focus her attention on her own mental (but not physical, body-related) experiences, and to arrive at judgments about them. But this is done with the explicit goal of training oneself to alter one’s natural judgments of what is good and what is bad, transferring those labels from externals (like health, education, wealth, etc.) to internals (i.e., one’s own judgments, considered opinions, endorsed values, and decisions to act).

As for the second point, that prosochē isn’t that fundamental in Stoicism, Greg points out a couple of interesting things. First, there are quotes (e.g., Meditations I.16 and XI.16) where the word is not used in anything like what Hadot, Fisher and Robertson suggest. For instance: “Because of his own attentions, he rarely had need of a doctor’s help, or medicines, or external treatment” (I.16). Here, “attention”—which is rendered by Marcus as prosochē—takes the normal, non-meditative meaning of the term. Marcus is just saying that we need to pay attention to things, in this case one’s health. As Greg comments: “These instances of the use of ‘prosochē’ seem to indicate that the term has pretty straightforward translation into English: ‘attention.’ These examples do not seem to have any connotations of ‘mindfulness’ that we’ve seen thus far.”

However, as Greg himself admits, we do find instances in Epictetus of a more mindfulness-like use of prosochē, particularly in Discourses IV.12, an entire section entitled “On attention.” Here is a pertinent passage:

“To what things should I pay attention, then? In the first place to those general principles that you should always have at hand, so as not to go to sleep, or get up, or drink or eat, or converse with others, without them, namely, that no one is master over another person’s choice, and that it is in choice alone that our good and evil lie. … And next, we must remember who we are, and what name we bear, and strive to direct our appropriate actions according to the demands of our social relationships, remembering what is the proper time to sing, the proper time to play, and in whose company, and what will be out of place, and how we may make sure that our companions don’t despise us, and that we don’t despise ourselves; when we should joke, and whom we should laugh at, and to what end we should associate with others, and with whom, and finally, how we should preserve our proper character when doing so.” (IV.12)

This sounds more like what Hadot & co. have in mind. Greg, however, has actually checked how many times the surviving Stoic texts use prosochē. Not many, as it turns out. It appears three times in the Meditations, ten times throughout the extensive writings of Seneca (in the Latin form, animum advertere, meaning “to turn the mind to”), and seven times in Epictetus.

While comparatively speaking this certainly does not constitute a high frequency of usage, I think Greg’s argument needs to be taken with a grain of salt here. For one thing, other important concepts also make only an occasional appearance in Epictetus—for instance, the three topoi referred to above. And yet even Greg agrees that the three disciplines (another notion, incidentally, originally popularized by Pierre Hadot) are indeed crucial to Epictetean philosophy. Moreover, let us not forget that the estimate by scholars is that close to 99% of Stoic writings has been lost. So statistical samples of the remaining 1% may not be as insightful as one might hope.

The flexibility of Stoicism, a qualified yes to prosochē

So, what are we to make about all of the above? I’m going to solomonically split the difference somewhere in the middle. I think Greg is right on both his main points: prosochē bears only a superficial resemblance to either sense of mindfulness in Buddhism (i.e., the ancient sati and the new Kabat-Zinn version). Also, it is true that the case for prosochē to be central in ancient Stoicism, or even just in the Epictetean variety, is at least questionable.

That said, I have no problem going with Hadot’s suggestion and re-interpret Epictetus in a way that is both innovative and yet clearly bears a family resemblance to ancient Stoicism. Hadot already did that in the case of the three disciplines of desire/aversion, action, and assent. It is just as doubtful that they were as central for Epictetus as we tend to use them today. Then again, Epictetus himself was clearly an innovator within Stoicism (for instance, he greatly improved upon the middle Stoic Panaetius’ theory of social roles). And let’s not forget that Seneca famously said:

“Will I not walk in the footsteps of my predecessors? I will indeed use the ancient road—but if I find another route that is more direct and has fewer ups and downs, I will stake out that one. Those who advanced these doctrines before us are not our masters but our guides. The truth lies open to all; it has not yet been taken over. Much is left also for those yet to come.” (Letters, XXXIII.11)

Indeed, between the re-evaluation and re-articulation of the three disciplines and his push for a more central role for prosochē, Hadot becomes the first and one of the most important innovators in modern Stoicism, on par with Larry Becker.

To redeploy the concept of prosochē to mean paying attention to all our morally salient choices, as they are unfolding in the here and now, seems to me to be very useful. And while it’s true that the best translation of prosochē is “attention,” the word just doesn’t convey the power of the concept as articulated by Epictetus. Since Buddhists don’t have a monopoly on the term “mindfulness” (and they disagree among themselves on what it means), it seems fair to talk about Stoic mindfulness, particularly when the modifier “Stoic” is added to the phrase, to avoid confusion.

We are modern Stoics, we are inspired but not constrained by what the ancients wrote. Practicing the three disciplines of Epictetus with mindfulness is eminently reasonable and practical. So let’s do it!

As a philosophical layman, I have the luxury of not having to have an opinion about what someone meant, but I do have a lot of curiosity, and a lot of respect for you professional philosophers. I appreciate your essays! My concern is what works for my practice and otherwise I suspend judgement. (I appreciate your writings especially because of your perspective is influenced by an academic skeptic approach.)

Meditation has been a great help to me in the last twenty years. I learned to meditate originally from a secular Buddhist group. I have never been able able to clear my mind of thoughts, but I have been able to detach myself from them, especially from any emotional charges that they may otherwise bring.

Where Stoic teachings have been helpful is that they allow me to engage in everyday life without my present experiences being filtered by my emotions from past experiences. Things like the dichotomy of control and other teachings help me remember that virtue is the priority, anything else I desire or fear is only a preferred or a dis-preferred indifferent.

The 3 disciplines of Epictetus has clarified a lot in 3 simple words. I would like to change the order. Desire is the root cause of suffering as the Buddha would put it. If there is no desire it prevents us from Judging & as a result our Action becomes easier to deal or accept other people.

Thanks for the essay. I always look forward on Monday mornings to read what you have thought about & now sharing it.